Colic (pain coming from the abdomen) is the number one medical problem of the horse. In my experience, it’s also the number one medical concern of horse owners, which is completely unsurprising. Even though the vast majority of horses that experience an episode of colic will not need surgery, if your horse has colic, you might be worried sick, regardless (and understandably so). However, since some colic problems are serious, the most important thing for you (and your veterinarian) to do is to quickly determine is if the problem is so serious that it requires surgery, and to make that determination as quickly as possible.

Like I said, most horses that colic don’t need surgery. However, it has been shown that the survival rate for horses getting colic surgery goes down the longer the horse has clinical signs of colic. This makes some sense, of course; whether it’s a horse, a car, a pair of socks, or anything else, you don’t want to try to start to fix things when they are falling apart; the outcomes tend to be a lot better if you get on the problem early. When it comes to your horse, if he has a colic, you need to find out if the problem requires surgery as quickly as possible, and you need to get him to the hospital as quickly as possible. The percentage of horses that get colic surgery that are put to sleep on the surgery table because of the advanced nature of their disease is estimated to range from 8% to 24%, so to avoid a sick horse being one of those awful statistics, and if colic surgery is a financial option for you, getting him to the hospital quickly is really important.

When I look at a horse with colic, I’m trying to gather a bunch of data to help me determine the likelihood that a horse is going to need to get to the hospital. If the horse needs to go for surgery, there’s no reason for me to keep him on the farm any longer than absolutely necessary. Of course, I don’t want to ship every horse to the clinic – that would just be a needless waste of time and money. So, when I look at a horse with colic, I’m looking at a whole bunch of factors to help me make my decision as to whether you can stay home, or if you have to hitch up the trailer (or start calling for one).

There’s no single diagnostic test that is 100% accurate at telling you if your horse with colic needs surgery. There are a lot of things that we look at. However, certain tests appear to more strongly predictive of the need for surgery than others. I think that it’s a good idea for you to know what they are.

STRONGLY POSITIVE PREDICTORS (the horse probably needs colic surgery)

Response to analgesia – If your horse has colic, and the most potent pain-relieving drugs, such as xylazine or detomodine don’t stop the colic pain, or if the pain starts back within a few minutes of receiving such drugs, it’s usually a sign that the colic pain is more serious and the the horse may require surgery for a chance at recovery. On the other hand, if your horse responds to those drugs, and the pain does not return, that’s usually a wonderful sign that surgery isn’t needed.

Response to analgesia – If your horse has colic, and the most potent pain-relieving drugs, such as xylazine or detomodine don’t stop the colic pain, or if the pain starts back within a few minutes of receiving such drugs, it’s usually a sign that the colic pain is more serious and the the horse may require surgery for a chance at recovery. On the other hand, if your horse responds to those drugs, and the pain does not return, that’s usually a wonderful sign that surgery isn’t needed.

NOTE: This rule does not apply to flunixin (Banamine®), which is not a potent pain-relieving drug. What I mean by that is that if your horse’s colic isn’t relieved by flunixin, it’s probably doesn’t mean very much. It’s also not a good idea to dump pain relieving drugs willy-nilly into a colicking horse without some sort of a diagnosis.

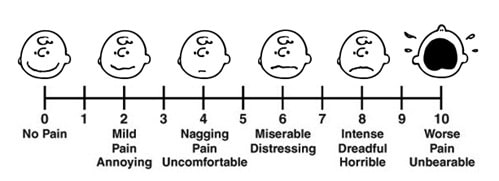

2. Degree of pain – This one’s pretty simple. The more painful the horse, the more likely he has a problem that needs surgery. The horse that can’t be kept up on his feet is more likely to have a serious problem than the one that occasionally looks back at his side, or one that is lying down relatively comfortably. The have been scales made to try to indicate the amount of pain – here’s one.

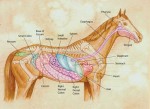

3. Abdominal fluid color and protein – This is a job for your veterinarian. There is fluid inside your horse’s abdomen that surrounds the guts (it’s called peritoneal fluid, which is useful to know if you want to impress your friends). In a horse with a colic that require surgery, over time, the peritoneal fluid typically changes color, and the amount of protein in the fluid typically increases. However, it is more likely that a horse with normal abdominal fluid does not need surgery than it is that a horse with abnormal fluid does need surgery. The procedure to collect abdominal fluid is called an abdominocentesis; it’s not a particularly difficult procedures in most horses but it is something that your veterinarian should do.

3. Abdominal fluid color and protein – This is a job for your veterinarian. There is fluid inside your horse’s abdomen that surrounds the guts (it’s called peritoneal fluid, which is useful to know if you want to impress your friends). In a horse with a colic that require surgery, over time, the peritoneal fluid typically changes color, and the amount of protein in the fluid typically increases. However, it is more likely that a horse with normal abdominal fluid does not need surgery than it is that a horse with abnormal fluid does need surgery. The procedure to collect abdominal fluid is called an abdominocentesis; it’s not a particularly difficult procedures in most horses but it is something that your veterinarian should do.

4. Abdominal distension – If your horse’s abdomen is blown up like a balloon – usually from gas in the intestines – it may indicate that he has a problem that needs surgery. Of course, the call is somewhat subjective, and some horses just get really gassy, but the association has been made in studies: twice.

5. Abdominal ultrasonography – Ultrasound of the abdomen allows veterinarians to look inside the horse’s abdomen and see what’s going on with the guts. Ultrasound is a very good predictor of the need for surgery. This test is going to be most likely done at the hospital but with proper training, it can be done in the field, as well.

STRONGLY NEGATIVE PREDICTORS (probably doesn’t need colic surgery)

STRONGLY NEGATIVE PREDICTORS (probably doesn’t need colic surgery)

1. Elevated body temperature – Colic typically does not cause horses to develop a fever. Fever is more consistent with things like infections or intestinal inflammation than it is with problems that need surgery. I’m not saying you should be happy if your horse with colic has a fever, I’m just saying that if he does have a fever, he probably doesn’t need surgery; at least there’s something to be hopeful about in an otherwise stressful situation. Oh, and a horse’s normal body temperature is between 99.5 and 101 degrees Fahrenheit (37.5 – 38.3 Celsius).

PREDICTORS OF MORE LIMITED VALUE (although commonly done, and sometimes still useful)

1. Rectal examination – A rectal exam – which for both horses and owners is one of the more curious and eye-opening parts of being an equine veterinarian, and in the winter, one of the warmer things, as well – is certainly important, but it’s not always a great predictor of the need for colic surgery. During a rectal examination, the veterinarian an arm in the horse’s rectum, and feels around inside the abdomen. Occasionally, a specific diagnosis can be made (say, if your veterinarian feels a “stone,” gas, or a gut full of hard manure, or abnormally distended bowel). However, about 60% of the abdominal cavity cannot be reached by a normal human arm. Otherwise stated, it may not be possible to feel what the problem is on a rectal exam, as impressive (or disgusting) as the procedure might seem. Thus, rectal examination may be of limited value in some cases: even those that need surgery.

2. Gut sounds – Roughly half of the horses that need colic surgery don’t have normal intestinal sounds (that’s something that your veterinarian can check with a stethoscope, or, if you have a stethoscope, you can try, too). Of course, that means that half of the horses that ultimately need surgery have good gut sounds, as well. It’s certainly important to listen to the abdomen of a horse with colic, but it’s also important to evaluate several other factors.

3. Mucous membrane refill time – Checking the time it takes for the blood to come back into the gums after light finger or thumb pressure has pushed the blood out, while commonly done, actually has fairly limited value as a predictor of surgery, unless the horse is really sick. The thumb print should refill in less than two second in normal horses, but if the colic goes on, and the horse starts to go into shock, changes in the capillary refill time and the character of the mucous membranes (from wet to dry) can be very significant. Unfortunately, for many horses, by the time things get to that point, it may be too late to do anything about the colic.

4. Mucous membrane color – Color and refill time sort of go hand in hand. A normal horse’s gums are a nice salmon pink – if they’re purple, it’s a sign that the horse probably needs surgery, but it’s also a sign that a lot of bad things have happened, and that the prognosis probably isn’t very good.

If your horse starts to colic, you might think about making a check list of the variables above and make a scorecard of sorts for your horse. Follow the signs, and if you’d consider referring him for colic surgery, try to do it as soon as possible.

If your horse starts to colic, you might think about making a check list of the variables above and make a scorecard of sorts for your horse. Follow the signs, and if you’d consider referring him for colic surgery, try to do it as soon as possible.

One other thing. If you’re not sure if a horse with colic has a serious problem, the conservative thing to do is to send him to the hospital. it’s always better to send a horse that doesn’t ultimately need surgery to the hospital and have him come back, than it is to wait too long to send him and not be able to do anything about it.

While colic is a big problem, happily, most horses with colic don’t need surgery. By looking at a few important clinical signs, you and your veterinarian should be able to make a decision to send the horse for colic surgery quickly. Hopefully, you’ll never have to do it.