Earlier in 2013, an American Association of Equine Practitioners Task Force released its “Parasite Control Guidelines.” In case you haven’t seen it, the full report can be seen if you CLICK HERE. But given that, 1) People get really worked up about the thought that their horse might have single worm in its intestines, and 2) The document is 24 pages long (including references), and it’s a bit dense, I thought I might give it a read and sum it up for you.

First off, the document is directed mostly at folks that keep horses in pastures. It also seems mostly to be directed at people that have more than one horse, or have a ranch or farm. I wrote an article about what I think you should be doing if you’ve got one horse, that mostly lives in a stall – CLICK HERE to read, “Stop Deworming Your Horse So Often.”

Anyway, the AAEP document really is pretty good, but it requires some patience to get through. Let’s start with four important points.

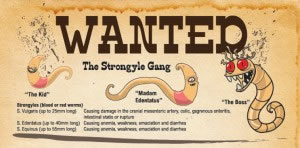

1. The parasites causing problems for horses now are mostly different from the ones that caused them problems a few decades back. The parasites that everyone used to get all worked up about – Strongylus vulgaris and other large strongyles, and which were mostly responsible for the horrible pictures that you’ve probably seen in deworming ads – are now actually pretty rare. The major parasites to worry about for adult horses are called small strongyles (cyathostomins), and, occasionally, tapeworms. For horses less than three years of age, ascarids (Parascaris equorum) are still the ones that cause the biggest problems.

1. The parasites causing problems for horses now are mostly different from the ones that caused them problems a few decades back. The parasites that everyone used to get all worked up about – Strongylus vulgaris and other large strongyles, and which were mostly responsible for the horrible pictures that you’ve probably seen in deworming ads – are now actually pretty rare. The major parasites to worry about for adult horses are called small strongyles (cyathostomins), and, occasionally, tapeworms. For horses less than three years of age, ascarids (Parascaris equorum) are still the ones that cause the biggest problems.

2. People have been deworming their horses so much that it’s now resulted in resistance to the common deworming agents, and especially with small strongyles and ascarids. If you keep dumping deworming paste into a horse that has resistant parasites, the parasites are just going to laugh at you (not literally, of course – you will not hear giggles coming from your horse’s abdomen).

2. People have been deworming their horses so much that it’s now resulted in resistance to the common deworming agents, and especially with small strongyles and ascarids. If you keep dumping deworming paste into a horse that has resistant parasites, the parasites are just going to laugh at you (not literally, of course – you will not hear giggles coming from your horse’s abdomen).

3. You should only treat horses that show signs of having a heavy parasite load. Adult horses actually develop immunity to parasites: some better than others. Those horses that have a high level of immunity don’t shed very many eggs. It doesn’t make any sense to deworm them all the time.

4. Horses less than about 3 years of age require special attention as they are more susceptible to parasite infection, and are more at risk for developing disease.

“So, Dr. Ramey,” you say, “What, exactly, are we supposed to do with that information?”

I’m glad you asked.

First of all, you’re supposed to change what you’ve been doing. The way that most people deworm their horse(s) is based on information that’s at least 40 years old. It’s not controlling internal parasites effectively, it’s wasting your time and money, and it’s building parasite resistance. Time to move into the 21st century.

First of all, you’re supposed to change what you’ve been doing. The way that most people deworm their horse(s) is based on information that’s at least 40 years old. It’s not controlling internal parasites effectively, it’s wasting your time and money, and it’s building parasite resistance. Time to move into the 21st century.

Since as long as anyone can remember, the goal of deworming horses has been to try to get rid of all of the parasites in an individual horse, that is, to try to make sure that an individual horse never has a single worm in its body. For most horses, that goal is – and I am using my words carefully here – impossible. Not only is it impossible, but trying to do it just helps breed drug resistant parasites. So, the goal is impossible and bad. That is not a good combination.

The true goal of parasite control in horses (and other equids, for those of you that keep donkeys or mules) should be to limit parasite infections so animals remain healthy and so that clinical illness does not develop. It’s OK if they have a worm or two. Don’t fret. Horses and worms have gotten along fairly well for, well, pretty much forever, as far as anyone can tell. You just want to make sure that the relationship doesn’t get out of control (kind of like a lot of relationships, actually).

So, here’s 14 (count ’em) bits of advice about how you effectively treat parasites, and help slow down the development of drug resistance.

1. WHICH HORSES? Horses – and especially horses over three years of age – should be treated as individuals and not according to some formula (every month or to, “rotating,” or whatever). You don’t have to deworm older horses all the time to keep them healthy. The baseline program should be one or two yearly treatments, depending on climate, and whether or not your horse lives with a bunch of other horses. If he lives by himself, or in a stables, it could be less.

1. WHICH HORSES? Horses – and especially horses over three years of age – should be treated as individuals and not according to some formula (every month or to, “rotating,” or whatever). You don’t have to deworm older horses all the time to keep them healthy. The baseline program should be one or two yearly treatments, depending on climate, and whether or not your horse lives with a bunch of other horses. If he lives by himself, or in a stables, it could be less.

2. WHICH DEWORMER? Ivermectin (a gazillion brands) and moxidectin (Quest®) are currently the best choices to control strongyle parasites. Pyrantel (e.g., Strongid®), fenbendazole (e.g. Panacur®), and oxibendazole (e.g., Anthelcide EQ®) are the best choices to treat ascarids in young horses – ivermectin resistance is common in ascarids.

3. WHAT IF I HAVE A LOT OF HORSES? If you’re on a farm, and you have lots of horses, use fecal egg counts to select the moderate and high egg shedders for deworming, and only treat those horses. You don’t need to test all of the horses, but you should test at least six to get some idea of how things are. If you have some in one pasture, and others in another pasture, you should test some in each pasture.

3. WHAT IF I HAVE A LOT OF HORSES? If you’re on a farm, and you have lots of horses, use fecal egg counts to select the moderate and high egg shedders for deworming, and only treat those horses. You don’t need to test all of the horses, but you should test at least six to get some idea of how things are. If you have some in one pasture, and others in another pasture, you should test some in each pasture.

4. HOW DO I DO FECAL COUNTS? Call your veterinarian. Testing feces for parasites is pretty cheap, and you should be working with your veterinarian anyway, to come up with the best program for your horse(s). He or she can advise you on the best test. And let your veterinarian do the test – if you send them out to some lab you’ve found on the internet, you’re not assured that the results are accurate, and it’s not fair to ask your him or her try to figure out what somebody else’s results mean.

5. WHAT IF MY HORSE SHEDS LOTS OF PARASITE EGGS? If you’re treating a high shedder, you will almost certainly need more than one or two treatments a year. Moderate and high egg shedders will need a third or fourth treatment for small strongyles – for those horses, you might want to consider using a daily feeding of pyrantel tartrate, or a dose of moxidectin. Any additional treatments would be given on an “as needed” basis depending what else you might see.

5. WHAT IF MY HORSE SHEDS LOTS OF PARASITE EGGS? If you’re treating a high shedder, you will almost certainly need more than one or two treatments a year. Moderate and high egg shedders will need a third or fourth treatment for small strongyles – for those horses, you might want to consider using a daily feeding of pyrantel tartrate, or a dose of moxidectin. Any additional treatments would be given on an “as needed” basis depending what else you might see.

6. WHAT IF MY HORSE IS A LOW SHEDDER? Some horses don’t shed very many eggs. Those that tend not to shed many eggs always tend not to shed many eggs (high shedders tend to always be high shedders). The low shedders probably don’t need to be treated more than once or twice a year, tops. Treating low shedders is not harmless – if you treat those horses, it just promotes drug resistance.

7. WHEN DO I DEWORM? Don’t deworm during the temperature extremes of cold winters or hot summers and during droughts. There’s no point. The parasites can’t reproduce effectively under such conditions. Worm control programs are best viewed as a yearly cycle starting at the time of year when worm transmission to horses changes from negligible to probable. Don’t know when that is in your area? Ask your veterinarian.

8. HOW DO I TELL IF THE DEWORMER IS WORKING? If you’ve got a herd of horses, and you’re worried about parasite resistance, do fecal exams at an appropriate interval after deworming. To see how well your dewormer is working to reduce egg shedding:

8. HOW DO I TELL IF THE DEWORMER IS WORKING? If you’ve got a herd of horses, and you’re worried about parasite resistance, do fecal exams at an appropriate interval after deworming. To see how well your dewormer is working to reduce egg shedding:

- – After moxidectin – Wait at least 16 weeks to collect a fecal

- – After ivermectin – Wait at least 12 weeks to collect a fecal.

- – After benzimidazoles (fenbendazole/oxibendazole or pyrantel) – sait at least 9 weeks to collect a fecal.

NOTE: If you do not wait long enough following treatment, then the results of the FEC will only show how well the last dewormer used work, rather than measuring how well the the horse’s immune system took care of levels of cyathostomin egg shedding.

9. WHAT IF I JUST HAVE ONE HORSE, AND HE’S NOT MIXING WITH OTHER HORSES? If you’re not on a farm, you may not need to deworm your horses at all. For example, here in southern California, I have horses that I’ve monitored, and NOT treated, for years. They live in stalls, they don’t mix with other horses, and their own manure gets cleaned up every day (usually). These horses may never need to be dewormed.

10. WHAT IF I’VE GOT YOUNG HORSES? Horses over three years of age should be treated differently than horses less than three years of age, mostly because horses less than three years of age are more susceptible to parasite infections that are older horses. Here are some specific guidelines for the youngsters.

10. WHAT IF I’VE GOT YOUNG HORSES? Horses over three years of age should be treated differently than horses less than three years of age, mostly because horses less than three years of age are more susceptible to parasite infections that are older horses. Here are some specific guidelines for the youngsters.

- During the first year, foals should get at least four deworming treatments. First deworming should be carried out at about 2 – 3 months of age, and a second treatment 3 months later. Check for eggs at weaning, to see what, if any, parasites are in the foal (NOTE: Don’t check right after you deworm, because you won’t find anything). Third and fourth treatments should be considered at about 9 and 12 months of age, targeting the worms that you find. Tapeworm treatment should probably be included on one of these latter treatments.

- Perform yearly fecal tests to evaluate how well the dewormers are working.

- Don’t worry about deworming a young foal at 8 days of age. This diarrhea isn’t caused by worms.

- Turnout recently weaned foals on the cleanest pastures.

- Yearlings and two year olds should be treated as “high” shedders, and should receive three to four yearly treatments with drugs that are shown to be working by fecal exam.

11. WHAT IF MY HORSE IS SHOWING SIGNS OF BEING PARASITIZED? Deworm him, using either moxidectin, or, possibly, a regimen of fenbendazole (10 mg/kg for five consecutive days). This kills not only parasites present, but larvae that get into the gut wall.

11. WHAT IF MY HORSE IS SHOWING SIGNS OF BEING PARASITIZED? Deworm him, using either moxidectin, or, possibly, a regimen of fenbendazole (10 mg/kg for five consecutive days). This kills not only parasites present, but larvae that get into the gut wall.

12. WHAT ABOUT ENVIRONMENTAL CONTROL? Great. Do it. Pick up manure as often as you can. Don’t spread manure around the pastures – you’re just spreading eggs. Oh, and if you have cattle or goats, let them rotate onto your horse pastures for a few weeks – parasites are species specific, so it won’t hurt them, and they will vacuum up the eggs.

13. WHAT ABOUT OTHER PARASITES? The two other parasites that people worry about are bots (which almost never cause problems), and pinworms (which can cause horses to itch their rear end). You can treat for bots once, traditionally 30 days after the first frost, and you can treat for pinworms if there’s a problem (your veterinarian can help you here).

14. WHAT ABOUT “ALTERNATIVE” DEWORMERS? Don’t bother. They don’t work. The effective products are very safe, and they’ve been proven to be effective. What else do you want?

There is no such thing as a “one size fits all” deworming program for your horse(s). And don’t make yourself nuts. Controlling parasites in your horse(s) just takes setting up a reasonable program and sticking with it. Your veterinarian can work with you to decide what’s best for your horses. It will save you time, money, and anxiety, and it’s best for your horse, too!

Thanks to Dr. Amy Grice, one of the authors of the AAEP Guidelines on Parasite Control, for her suggestions and comments.