Equine Cushing’s Disease – also known as Pars Pituitary Intermedia Disorder (which is hard enough to say that it’s a reason that the name Equine Cushing’s Disease sticks, and the reason that everyone abbreviates it to PPID) – is a relatively common problem affecting older horses, say, on average, about 18 years and older. It has been described in younger horses, but that’s when I usually see it. Cushing’s Disease is named after the guy who first described the condition (in people), the father of modern neurosurgery, Harvey Cushing (you really should read this guy’s biography – his accomplishments were just amazing).

Cushing’s Disease in horses is a little bit different than the condition of the same name that occurs in people and dogs, but one thing that they all have in common is that affected individuals have a problem in their pituitary gland. The pituitary gland is located right at the base of the brain, and among its functions is acting as a kind of traffic cop, directing the production of various hormones in the horse’s body. Not enough cortisol in the body – wave the production on! Too much? Raise your hand and hold things up. Normally, things run smoothly.

When a horse gets Cushing’s Disease, the traffic cop just keeps twirling his arms, waving production on with nary a thought as to the consequences. The gland enlarges, and can even compress important structures next to it (it’s also sometimes called a pituitary adenoma, that is, a growth of the glandular tissue, but the disease in not cancerous). The problems and changes that occur are largely as a result of the overproduction of hormones.

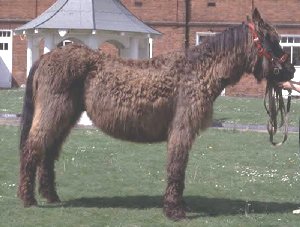

It can be difficult to recognize the problem in its early stages. The first hints are often in the hair coat – affected horses may not shed normally, or may start drinking and urinating a lot. The “classic” sign is of a horse that looks like a wooly mammoth, with a long, curly hair coat (no tusks).

HUMOROUS ASIDE: There’s really nothing else that gives older horses a long, curly hair coat. Once you’ve seen one, you’ve pretty much seen them all. In fact, one day, I was walking through a barn with my older son, who was all of 8 years old at the time, and who had regularly accompanied me on my veterinary rounds. At the end of the barn aisle was an old white horse, with the classic Cushing’s hair coat. Of course, no one has ever thought of 8 year-olds as being models of tact and diplomacy, so, upon seeing the horse, he points and yells out, “Hey, Dad! That horse has Cushing’s!” The owner looked at me, annoyed, and I shrugged my shoulders and said, “Well, he’s probably right.” Frankly, I thought the owner should have been glad not to have to pay for the diagnosis, or at least offer to buy him an ice cream cone.*

Typical appearance of horse with Cushing’s Disease. Note differences between horse and wooly mammoth, above.

There are some other signs associated with Cushing’s Disease, including lethargy, sweating, loss of muscle tissue, repeated infections, and infertility (although, frankly, most people aren’t breeding 18 year old horses much. The real problem for many of these old, hairy horses is that the excess production of cortisol can help trigger laminitis; that can be a real mess.

If a horse doesn’t have obvious signs of Cushing’s Disease, and you’re worried, it’s best to test him. There’s no generally accepted “best” test. There are dexamethasone suppression tests,** resting levels of ACTH, a hormone regulated by the pitutary gland,*** and TRH (thyroid releasing hormone) stimulation tests, too. No test is 100% accurate, and your veterinarian will probably use the test with which he or she is most comfortable. I tend to use the ACTH test. There’s some fall of in accuracy in the fall months, so that can be a pain.Of course, if you have an old, hairy, long-haired horse who isn’t shedding, there’s really little reason to do any testing at all.

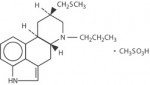

Chemical structure of pergolide mesylate (I needed an illustration, and didn’t have any better ideas).

With any medical condition, the ideal treatment is to fix the problem. Unfortunately, with Equine Cushing’s that’s not an option. There’s no surgery available to remove the enlarged portion of the pituitary gland (you’d kill the horse trying), and there’s no medical treatment available to shrink the gland, either. Happily, there is treatment that can help some. It’s a drug called pergolide, which is also treatment option in some countries for human Parkinson’s Disease. It’s available as a pretty pink pill that horses seem to eat pretty well. All horses don’t respond equally well to the drug, so make sure you work with your veterinarian to establish proper dosing. You should wait at least two or three months before you draw any conclusions about how well the drug is working, or before you consider changing the dose. Treated horses may not even lose their hair until the next season.

Like most conditions, when there’s no cure, lots of treatment “options” will rush in to the breach, offering to “help.” These are mostly just a waste of your time (and money). One popular treatment seems to be chasteberry,**** a relatively attractive herb that has been prescribed through history for women with menstrual problems, and which has active ingredients that might mimic some of the effects of pergolide. The problem is that it doesn’t work (a study at University of Pennsylvania showed that). Neither do any of the other supplements that are out there. I completely understand wanting to do “everything” to treat your horse, but it’s pointless to pay for something that does nothing. Stick to proven effective treatments, such as pergolide, as well as things like proper dietary management, and regular routine care. Happily, most horses with Equine Cushing’s Disease can be managed fairly well, and most of the ones that I’ve taken care of have lived good, long lives.

There are all sorts of resources out there about Equine Cushing’s, some of which are better than others. The American Association of Equine Practitioner’s webpage has a nice – albeit somewhat dryer – description of Equine Cushing’s Disease, it’s diagnosis, and management. CLICK HERE to see what they have to say.

Cushing’s is such a common condition in older horses that it really deserves another article. And that one, which will answer some common questions about the condition and its treatment, will be coming along soon!

*************************************************************************************************************************************

* Yes, it is somewhat annoying to find out that any part of your job can be performed by an 8 year old with keen powers of observation.

** The dex suppression test is an indirect test. Dexamethasone looks and acts just like plasma cortisol, as far as the body is concerned. If you give a normal horse a big blast of dexamethasone, the normal pituitary gland holds up its hand and slows down the production of cortisol. But in horses with Cushing’s disease, the gland just keeps waving the production along. Labs can test for cortisol – if the horse has high levels of cortisol about 20 hours after having been given a big blast of dex, chances are that he has Cushing’s disease.

*** ACTH stands for adrenocorticotropic hormone. I readily acknowledge that it’s there, even though I barely remember what it does. If you want to read more about it, and you have that kind of time, CLICK HERE.

**** The name of the plant is due to the fact that historians say that monks chewed parts of the tree to make it easier to maintain their celibacy. I have no idea whether it was effective.

**** The name of the plant is due to the fact that historians say that monks chewed parts of the tree to make it easier to maintain their celibacy. I have no idea whether it was effective.