You may have heard that it’s a good idea to have your horse checked to see if it needs to get its spine “adjusted” by a “chiropractor.” Before do that, here’s what you should know.

Doctors of Chiropractic (a degree granted by chiropractic schools) are not trained to work on animals. No part of chiropractic education deals with animals. Furthermore, no part of veterinary education deals with manipulative forms of physiotherapy. In most states, the practice of chiropractic is, by definition, restricted to humans (a definition supported by a 1998 decision of the appeals court of the state of Michigan). Nevertheless, some chiropractors purport to be able to ply their trade on animals, and some veterinarians say that they can perform chiropractic adjustments. There are a few doctors hold both chiropractic and veterinary degrees. There also appear to be many animal “chiropractors” who have neither veterinary nor chiropractic degrees, but who may assert that they have enough experience to do the job nonetheless.

The claims made for chiropractic in horses may be, quite simply, incredible. One Wisconsin chiropractor, for example, says that “Chiropractic care offers a natural, drug-free adjunct to . . . total health care” and is suitable for cats, dogs, and horses with: back, neck, leg, or tail pain; carpal tunnel syndrome; degenerative arthritis; disc problems; head tilt; injuries resulting from slips, falls; TMJ problems, difficulty chewing; pain syndromes; sciatic neuralgia; sudden changes in behavior or personality; uneven muscle development; uneven pelvis or hips; weight loss due to pain; “a look of apprehension or pain in the facial expression”; and various other problems.

From a legal perspective, practicing on animals is restricted to veterinarians in all states. Technically, chiropractors may work on animals under the direct supervision of a veterinarian if the veterinarian feels that such treatment is warranted. However, in doing so, the chiropractor is working as an unlicensed veterinary technician. Accordingly, anyone manipulating animals who is not a veterinarian or working under direct veterinary supervision is likely to be breaking current laws.

The American Veterinary Chiropractic Association is the primary organization that “certifies” DVMs or DCs after 150 hours of coursework and also offers “advanced” courses. The idea that 150 hours can provide a chiropractic or veterinary education seems odd, and the Association does say that its certification is just the beginning. As scanty as 150 hours may seem, one-day seminars are also offered on animal adjusting. One wonders what members of the chiropractic associations might say if veterinary profession started giving one-day clinics on human chiropractic.

Unfortunately, fundamental aspects of chiropractic are unscientific, and many of the “lesions” identified by chiropractors cannot be demonstrated. For example, a chapter in 1998 textbook intended for veterinarians states:

Chiropractors identify subluxations of the spine during clinical examinations and then proceed to correct these lesions by specifically adjusting the involved segments. . . . An adjustment is a specific physical action designed to reinforce the biomechanics of the verterbral column and indirectly influence neurologic function. . . .

For the veterinarian who understands the elements of holistic practice and the philosophy of chiropractic, every patient becomes a possible chiropractic patient. Every examination should include a spinal examination, and every treatment protocol should include an adjustment if necessary.

Some “veterinary chiropractic” advocates assert that spinal problems result in problems with other organ systems. From the same book:

Many practitioners believe that the spine is not worth checking unless a musculoskeletal problem is being examined; however, every cell in the body has a nerve supply originating in the nervous system. The nervous system is therefore important to the health of all organ systems, and a chiropractic examination is advised for every patient. . . .

Chiropractic is an excellent way to build a veterinary practice because it includes preventive care after the initial problem is solved.

The main reasons for practicing veterinary chiropractic on horses, as mentioned above, are economic, not based in medical reality. For example, the primary lesion of chiropractic, the “subluxation,” has never been demonstrated. On another front, some organs and cells function independently of nerve supply; and there is no reason to believe that spinal adjustment does anything at all in such instances.

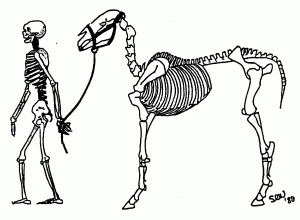

But even if the various theories of chiropractic were completely valid, it should be obvious from a mechanical standpoint that the forces on the spine of an animal that walks on four limbs are quite different from those of humans who walk on two. Thus, even if human chiropractic theories were plausible, direct application to animals might not be warranted. For example, since the vertebrae of horses are the size of the adult fist and surrounded by muscle, tendon, and ligament layers several inches thick, it seems reasonable to wonder whether equine vertebrae can actually be manipulated at all.

Of course, all of these concerns beg the question of whether “adjusting” horses really works. No scientific studies show that chiropractic adjustment does anything useful in any animal. It may be reasonable to surmise that moving an animal’s limbs around, massaging its muscles, or giving it any sort of attention might be well-received by the animal, but there is no evidence that such attention can improve health (and there’s no reason you’d need a specialist to do it). Furthermore, no published study has ever shown how a chiropractic-related problem can be diagnosed in animals or how treatment success can be determined.

There are also potential dangers. Chiropractic manipulation in humans usually entails short, thrusting movements applied at segments of the spine or at specific joints. Horses have been injured by overly aggressive maneuvers described as animal “chiropractic.” No part of chiropractic theory suggests that mallets, hammers or boards — devices that have made an appearance in the horse world — should ever be used. (Indeed, the chiropractic-veterinary group itself decries the use of such devices.) Dramatic movements that stretch beyond the limits of normal range of motion — for example, the lifting of a horse’s hind leg over its back — are potentially harmful. Nor should any animal be manipulated under tranquilization or general anesthesia.

It’s easy to see how owners who want to do the “best” for their horses could be convinced by unscrupulous or naïve professionals that “people need adjusting — animals must, too!” The human-animal bond is strong. However, that bond should not be abused under the guise of unproven “therapy.” There is no scientific evidence that any ailment of the horse is amenable to spinal manipulation.