Do you feel the same way every day? I mean, I don’t. Some days, I rocket out of bed, enthusiastic and eager for every challenge. Other days? Not so much. On those days I’d rather snuggle with my Puggle (“Funny Lookin'” – “Funny,” for short – adopted from the pound a couple of years back, and now a tail-wagging fixture of my home) and let the day go by. Some days I wake up ready to take on the world. Others, I’d just as soon pull the covers over my head and let the world go by.

Why don’t I feel the same way every day? There’s a word for that: “Normal.” It’s happens to all of us.

Medical issues are like that, too. There are good days and there are bad days. Take osteoarthritis, for example. The disease has taken away the soundness of many good horses. But even so, a horse with osteoarthritis will have good days and bad days. Some days, he’ll move eagerly and can even go out for a ride. Others, he’ll have an obvious limp that will hurt you almost as badly as it hurts him. And, of course, that’s when you’ll especially want to help.

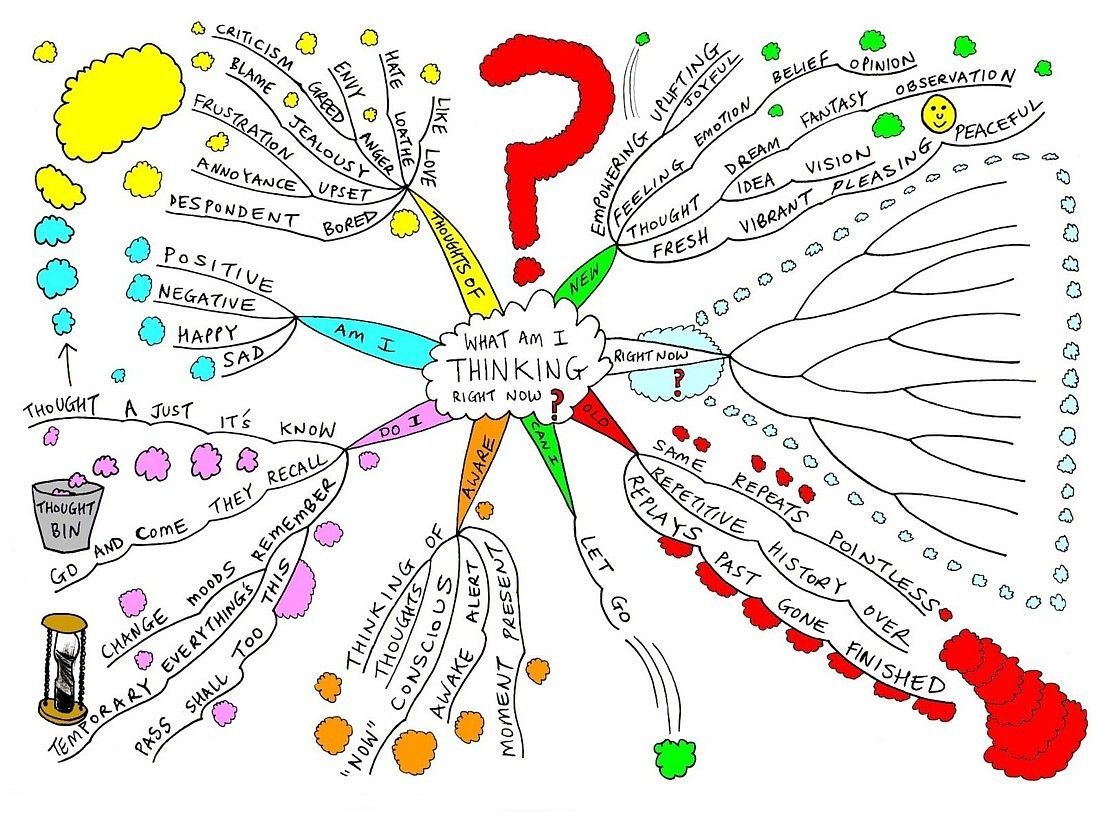

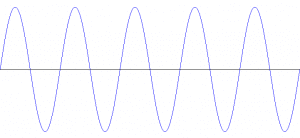

If you kept track of every day, and you marked down the good days and the bad days, you might get a graph that looks something like this:

The good days are the high points – the bad days are the low points. And the line that runs through the middle is the average. That is, on average, the line represents how you’re horse is going to feel on just about any given day, plus or minus. (Works the same way for you, too.)

The good days are the high points – the bad days are the low points. And the line that runs through the middle is the average. That is, on average, the line represents how you’re horse is going to feel on just about any given day, plus or minus. (Works the same way for you, too.)

So let’s now say that your horse has some sort of a problem: real or perceived. He’s going to have good days and bad days. But chances are that you’re going to be worried the most on the bad days. And those worry-filled days are the ones that you’re going to want to seek out some sort of treatment: some injection, some procedure, some supplement, some pill. I mean, why in the world would you worry about giving some medication, therapy, or “support” when your horse is feeling as good as he possibly can? It’s when things are bad that we seek help.

So let’s now say that your horse has some sort of a problem: real or perceived. He’s going to have good days and bad days. But chances are that you’re going to be worried the most on the bad days. And those worry-filled days are the ones that you’re going to want to seek out some sort of treatment: some injection, some procedure, some supplement, some pill. I mean, why in the world would you worry about giving some medication, therapy, or “support” when your horse is feeling as good as he possibly can? It’s when things are bad that we seek help.

So why does this matter? Well, when it comes to finding out if therapies really do anything or not, it’s a critically important consideration, and one that has to be thought of when analyzing the results of any experiment. It even has a name: “Regression to the Mean.” The concept of regression comes from genetics. It was popularized by Sir Francis Galton, during the late 19th century,

ASIDE: Wikipedia describes Galton as, “An English Victorian statistician, progressive, polymath, sociologist, psychologist, anthropologist, eugenicist, tropical explorer, geographer, inventor, meteorologist, proto-geneticist, and psychometrician.” I can’t figure out how so many folks in previous centuries seem to have had so much time to do so much stuff. I barely have time to pet “Funny,” much less explore the tropics. But I digress.

But back to your horse. Take a look at the graph again. If you seek treatment on the bad days – on the bottom of the curve, as it were – it’s very possible that you’ll be fortunate enough to select a treatment that really does help. But it’s also possible that you’ll be selecting a treatment that coincides with an upswing in the curve. And there’s the rub (a phrase with, by the way, comes from the celebrated, “To be, or not to be” speech in Shakespeare’s Hamlet, which was written back in 1602).

Once you get the concept of regression to the mean helps explain a lot of things that can make evaluating treatments so confusing. Ever try something for your horse, find that it “works” initially, but then it stops? It wasn’t the fault of the something – you just tried it at a time when the condition was getting better anyway. Your horse is limping, so you get him one of the 1,249,315 joint supplements out there. And he gets better. It could have certainly been the joint supplement. But it might also be things coming back towards the mean. In fact, given that no joint supplement has even been shown to consistently do anything (other than cost money), it’s most likely that’s exactly what’s happening.

There are all sorts of other examples. You’re concerned that you’re not riding well because the saddle isn’t fitting properly. So, you go to the bank, take out a second mortgage, and get a custom saddle fitted for your horse. He’s better. You feel somewhat better, too (although you still suffer from sticker shock), But was it really the saddle? It certainly could have been. But it might also have been that he was going through a bad time, and he was going to get better anyway. Or, perhaps the new saddle gave you some more confidence. Perhaps he’s not any better but you have to think that he is, so that you don’t get overly depressed about having just spent your vacation money on your horse. When it comes to evaluating therapies, there are all sorts of reasons why things can seem better.

There are all sorts of other examples. You’re concerned that you’re not riding well because the saddle isn’t fitting properly. So, you go to the bank, take out a second mortgage, and get a custom saddle fitted for your horse. He’s better. You feel somewhat better, too (although you still suffer from sticker shock), But was it really the saddle? It certainly could have been. But it might also have been that he was going through a bad time, and he was going to get better anyway. Or, perhaps the new saddle gave you some more confidence. Perhaps he’s not any better but you have to think that he is, so that you don’t get overly depressed about having just spent your vacation money on your horse. When it comes to evaluating therapies, there are all sorts of reasons why things can seem better.

Thomas Fuller, an English theologian and historian (another one of those guys), seems to have been the first person to write down the idea that the darkest hour is just before the dawn, meaning, of course, that there is always hope, even in the worst of circumstances. Fuller wrote a religious travelogue called A Pisgah-Sight Of Palestine And The Confines Thereof, 1650, in which he states: “It is always darkest just before the Day dawneth.” That’s a pretty wise thought when it comes to considering doing something to your horse.

Thomas Fuller, an English theologian and historian (another one of those guys), seems to have been the first person to write down the idea that the darkest hour is just before the dawn, meaning, of course, that there is always hope, even in the worst of circumstances. Fuller wrote a religious travelogue called A Pisgah-Sight Of Palestine And The Confines Thereof, 1650, in which he states: “It is always darkest just before the Day dawneth.” That’s a pretty wise thought when it comes to considering doing something to your horse.

Of course, there are conditions with which your horse is going to need immediate help. If your horse is bleeding from a big cut, or has a painful colic, or has a high fever, or can’t walk (to name a few), it’s probably not a good idea to just wait and see what happens. But if your horse has a chronic condition, the necessity for immediacy usually isn’t there. Your veterinarian should be happy to help you decide what to do.

Just like the tides, medical conditions can ebb and flow. Keep in mind that they’re not necessarily ebbing and flowing because of something that you’re doing. It might help you worry and spend less, and enjoy your horse more.