Here’s a a concept that you may not have thought of. It’s called biological plausibility.

Here’s a a concept that you may not have thought of. It’s called biological plausibility.

Biological plausibility is a really important concept when it comes to discussing therapies. It also helps explain when many people in medical and scientific professions (including me) express doubts about a whole bunch of therapies, even in the face of, “But it works for me” sorts of testimonials. When it comes to knowing that a therapy actually does something important for your horse (as opposed to being really darn sure that it does something because you saw a change or because somebody told you that something was really great), biological plausibility is a serious consideration. Unfortunately, it’s a consideration that’s often ignored.

Here’s what I’m talking about. Say some friends just came back from a camping trip to the Colorado mountains. While filling you in on all of the wonderful and scenic details of the trip, they confided in you that in addition to all of the wonderful relaxation and satisfaction that they got from enjoying the great outdoors, they had stumbled across an amazing canyon (let’s call it “Levitation Gulch”). The amazing thing about this canyon was that here, the law of gravity was suspended. You could walk up to the edge, step off, and, amazingly, you wouldn’t fall. You could just cruise on over to the other side of the canyon. What a vacation!

At this point, you have one of two choices. You can congratulate your friends on their great vacation, ask for a map, buy a plane ticket, and run out and step out over the abyss yourself. I mean, you undoubtedly like your friends, and you’re glad they had a nice trip, and you’re really curious about what-the-heck they’re talking about.

At this point, you have one of two choices. You can congratulate your friends on their great vacation, ask for a map, buy a plane ticket, and run out and step out over the abyss yourself. I mean, you undoubtedly like your friends, and you’re glad they had a nice trip, and you’re really curious about what-the-heck they’re talking about.

But something is still nagging at you. It’s this law of gravity thing. You’ve become pretty happily accustomed to being fairly well stuck to the planet. Everywhere that you’ve gone, you’ve found that if you jump up in the air, you’ll come right back down to the ground. Gravity is a law, not just a suggestion. So, your other choice – in spite of your inclination to want to believe your friends – is to have some pretty serious doubts about their story because, well, it’s just wildly implausible.

A lot of medical claims are like that, too. It’s all well and good to be open-minded to the possibility that some implausible therapy might have an effect, but you can’t be so open-minded that your brain falls out. You have to consider the plausibility of what you’re being told.

A lot of medical claims are like that, too. It’s all well and good to be open-minded to the possibility that some implausible therapy might have an effect, but you can’t be so open-minded that your brain falls out. You have to consider the plausibility of what you’re being told.

It’s always good to illustrate with examples, so let’s run through a few therapies, and biological plausibility standards, just so can you can see what some biological problems that beset some “promising” or popular therapies.

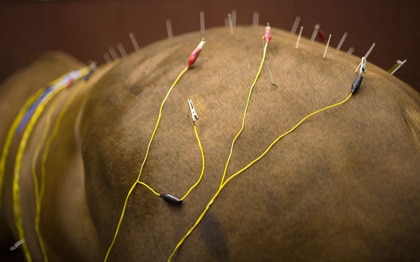

ACUPUNCTURE

There’s been lots and lots of research done on acupuncture – some good, and a lot bad – and mostly in human medicine. You can certainly find individual studies that support just about any point of view that you want to take, but it can be said with some assurance that:

Nobody has ever shown such things as “acupuncture points” to exist as real structures (real, say, in the same way that an ear is an identifiable structure)

Nobody has ever shown such things as “acupuncture points” to exist as real structures (real, say, in the same way that an ear is an identifiable structure)- Nobody has even shown that such things as “meridians” – the putative channels through which some (but not all) proponents of acupuncture say a vital energy (‘qi”) travels

- It doesn’t seem to matter much where you stick the needle to get an effect, that is, most studies that stick a needle just anywhere and compare if to sticking it somewhere it particular can’t seem to show a difference

- The “energies” that are affected by acupuncture (according to some) have never been measured.

There’s lots more, but that’s not my point. It’s certainly possible that acupuncture is an important medical procedure – even though,nobody has been able to show that it consistently does anything – but if you start talking about mysterious energies, and the importance of specific points (among several other things) you’re talking about a limb that’s not really attached to a plausible tree.

Here’s one example. Energy is something that can be measured. And scientists are really good at measuring it. They can measure the spin of sub-atomic particles, which are pretty much smaller than the limits of human imagination. They can measure the considerable energy in biological systems, too. But when it comes to “healing energies,” you know, “energies” that flow along supposed channels in the body, or that can be transmitted to this spot or that, well, nobody seems to be able to find them. You’d think that if an “energy” were powerful enough to affect the very real energetic systems of the horse’s body that you’d be able to measure them. But, so far, “healing energies” have escaped detection by even the most sensitive measuring devices. You really have to wonder if they are there at all. On the other hand, there may be lots of more productive things to wonder about.

So, from a plausibility standpoint, it would be better to say, “Hey, I had some little needles stuck n my horse and he got better (from whatever was making him not good).” That’s not entirely implausible, because sticking a needle in a body demonstrably does something. You can test whether it does something, too (and, so far, it doesn’t really seem to do anything specific). But when you start to lump in all of the implausibilities, the therapy becomes much harder to swallow.

So, from a plausibility standpoint, it would be better to say, “Hey, I had some little needles stuck n my horse and he got better (from whatever was making him not good).” That’s not entirely implausible, because sticking a needle in a body demonstrably does something. You can test whether it does something, too (and, so far, it doesn’t really seem to do anything specific). But when you start to lump in all of the implausibilities, the therapy becomes much harder to swallow.

BRIEF ASIDE: The ancient Chinese also believed that dinosaur bones were dragon bones. Since dragons have not been shown to exist, it’s at least implausible claim to point to a toe of T. Rex and assert that it really belonged to Puff (the Magic Dragon). I hope you’re getting my point.

You can buy homeopathic nostrums at the drugstore. You’ll even find some practitioners who assert that homeopathic remedies should be used on animals. But this is all in the face of the fact that homeopathic remedies are so wildly implausible as to defy explanation. They are so dilute that they can’t possibly do anything. I mean, gasoline doesn’t get more powerful as it gets more dilute, right? You’re favorite alcoholic beverage won’t make you more tipsy if you first pour it in a swimming pool first, right? Nevertheless, homeopathy still has its proponents, and even a few (mostly older) studies to support it’s use. Homeopathy is sort of the poster child for biological implausibility, and unless someone can prove that there’s some mechanism of action that has eluded science for, oh, 225 years or so, it doesn’t seem to be unreasonable to dismiss it altogether. Or people can keep waiting, or believing… I guess.

LEGEND®

Legend®, is the stuff that people inject into horse veins to try to help their joints. While your experience may differ from mine (in my opinion, it doesn’t do anything), it’s biologically implausible to think that if you put about 25% of the amount of a substance that a horse produces every single day into the horse’s bloodstream every once in a while, and that 25% only lasts a few hours, it’s going to make some dramatic difference in your horse’s joint health for a month or more. It’s like saying that if you’re talking while attending a football game, and you stop, your silence is going to be noticed by the roaring crowd – and they’ll notice it for the next three games, too. Possible, I guess, but pretty implausible.

Legend®, is the stuff that people inject into horse veins to try to help their joints. While your experience may differ from mine (in my opinion, it doesn’t do anything), it’s biologically implausible to think that if you put about 25% of the amount of a substance that a horse produces every single day into the horse’s bloodstream every once in a while, and that 25% only lasts a few hours, it’s going to make some dramatic difference in your horse’s joint health for a month or more. It’s like saying that if you’re talking while attending a football game, and you stop, your silence is going to be noticed by the roaring crowd – and they’ll notice it for the next three games, too. Possible, I guess, but pretty implausible.

GLUCOSAMINE

It seems like just about every product for horses (or small animals, for that matter), has glucosamine in it. That’s because glucosamine is supposed to be “good” for joints (whatever “good” means). But there’s a problem. Good research has shown that if you give glucosamine to horses at the doses that are typically recommended – and nobody seems to know how those doses were determined anyway – you end up with concentrations of glucosamine in the serum and joint fluid that are at least 500-times lower than those that have been reported to do anything to joint cartilage cells in tissue and cell culture experiments. So, the first question then becomes, “How’s it supposed to work? It’s just biologically implausible. That’s probably why nobody has been able to show a consistent effect for at least three decades (but who’s counting?).

It seems like just about every product for horses (or small animals, for that matter), has glucosamine in it. That’s because glucosamine is supposed to be “good” for joints (whatever “good” means). But there’s a problem. Good research has shown that if you give glucosamine to horses at the doses that are typically recommended – and nobody seems to know how those doses were determined anyway – you end up with concentrations of glucosamine in the serum and joint fluid that are at least 500-times lower than those that have been reported to do anything to joint cartilage cells in tissue and cell culture experiments. So, the first question then becomes, “How’s it supposed to work? It’s just biologically implausible. That’s probably why nobody has been able to show a consistent effect for at least three decades (but who’s counting?).

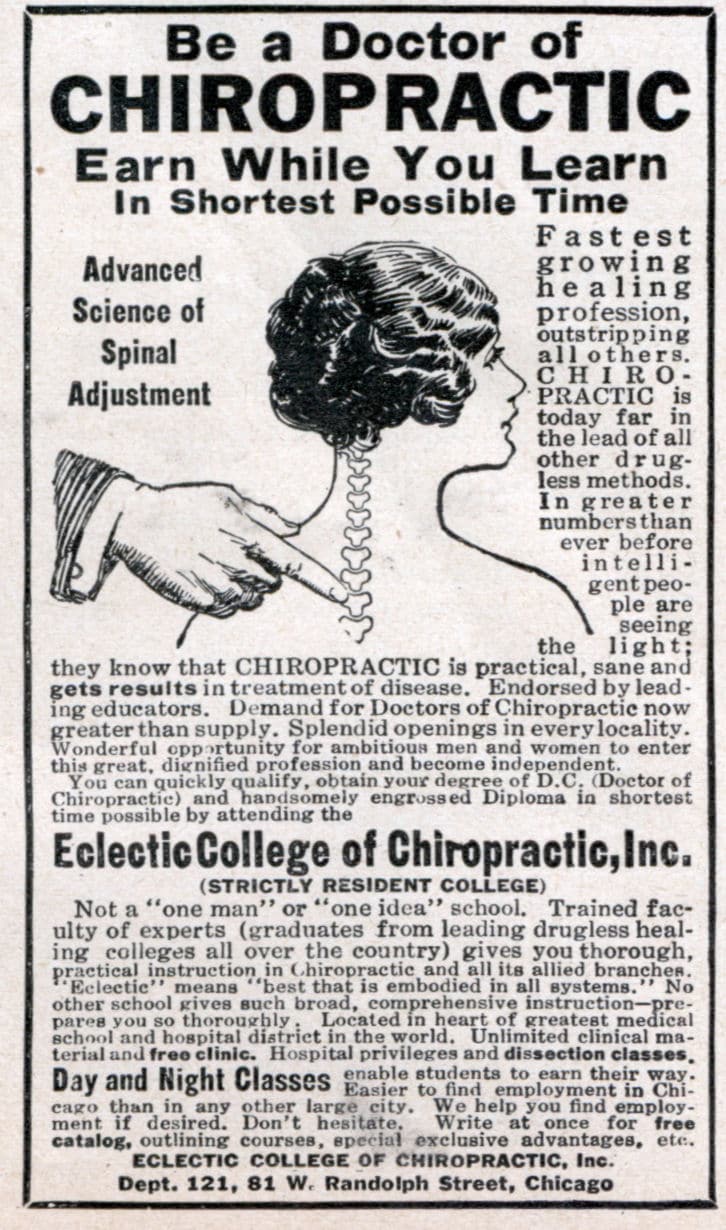

CHIROPRACTIC

There are very few therapies that simultaneously elicit as much support and disdain as does chiropractic. I’m not going to get into those in this article, and if your your horse has been helped by someone who calls himself an “equine chiropractor” – even if you think they’ve been helped – I’m really happy for you. Still, the biological plausibility issue is a big issue for chiropractic. For example:

There are very few therapies that simultaneously elicit as much support and disdain as does chiropractic. I’m not going to get into those in this article, and if your your horse has been helped by someone who calls himself an “equine chiropractor” – even if you think they’ve been helped – I’m really happy for you. Still, the biological plausibility issue is a big issue for chiropractic. For example:

- Spinal or rib bones being “out of place” have never been shown to exist

- “Innate” energies that some chiropractors say are responsible for healing don’t exist

- It’s not possible to deliver “specific” thrusts to particular vertebrae, especially since horses have such big muscles

That’s not to say that a horse couldn’t conceivably be helped by pushing and pulling and twisting on his body (even though that hasn’t been shown in good studies), it’s just that a lot of the underlying stuff is pretty implausible, biologically speaking.

ANESTHESIA

You don’t always have to know why something works to show that it does work. So, for example, nobody is exactly sure why gas anesthetics work. Of course, exactly nobody argues that they do work, which is why, say, every single hospital on the planet uses anesthetics when they do surgery. As for how anesthetics work, they actually do have some ideas – in fact, here’s a fascinating podcast about the whole subject (it’s the first story).

If someone told you that they worked because, oh, there was some evil spirit in the gas that stole your oxygen, you’d certainly have a good reason to shake your head. The fact that anesthetic gas works isn’t implausible, but some of the explanations that have been made for them certainly were. Science doesn’t always work quickly, but it usually gets there.

What makes trying to decide if treatments work so confounding is that, when it comes to dealing with horses (or any living system), we’re dealing with something that is trying to get better anyway. So, if you add something that’s wildly implausible to a condition that might be getting better anyway, it’s at least possible that the thing that’s implausible is going to get credit for the improvement. In fact, in another one of Ramey’s Rules, the weirder and more implausible the therapy, the more likely it is to get credit in case something does get better.

What makes trying to decide if treatments work so confounding is that, when it comes to dealing with horses (or any living system), we’re dealing with something that is trying to get better anyway. So, if you add something that’s wildly implausible to a condition that might be getting better anyway, it’s at least possible that the thing that’s implausible is going to get credit for the improvement. In fact, in another one of Ramey’s Rules, the weirder and more implausible the therapy, the more likely it is to get credit in case something does get better.

Of course, it’s a fact that we don’t know everything. But we certainly do know something. So it’s kind of silly to say that some implausible therapy might work because we don’t know everything. We can’t know everything, but what we do really know, we know pretty darn well. If something’s biologically implausible, and if its implausibility flies in the face of what we know pretty darn well, and if you swayed by it nonetheless, well, you might just be stepping off into Levitation Gulch. Good luck with that.