So, I went to the American Association of Equine Practitioners Convention (December 6 – 11, 2013, in Nashville, TN). In addition to speaking on ethics in equine medicine, and having one of the best meals of my life (if you are ever going to Nashville, try to get into the Catbird Seat – you will not regret it), I also sat in on a very long lecture given by Dr. Sue Dyson. Dr. Dyson has made a great career for herself in Newmarket, England, where she’s achieved notoriety for her investigations into lameness. She is also one of the most meticulous record keepers that veterinary medicine has ever seen, and, as a result, she’s constantly publishing really great, well-researched, and well-documented articles about horse lameness, that involve lots of horses, articles that usually give great insight into various treatments and diagnostic approaches.

Anyway, every year at the AAEP they have this lecture devoted to a single topic, named after the late Dr. Frank Milne (1919 – 1990, who, in addition to many other accomplishments, edited the AAEP Proceedings for many years). The lecture is meant to sum up the “state of the art” about a topic of interest to pretty much everyone who takes care of horses (which is why they hold the lecture in a very big room). Dr. Dyson’s topic was “Equine Lameness: Clinical Judgment Meets Advanced Diagnostic Imaging.”

Anyway, every year at the AAEP they have this lecture devoted to a single topic, named after the late Dr. Frank Milne (1919 – 1990, who, in addition to many other accomplishments, edited the AAEP Proceedings for many years). The lecture is meant to sum up the “state of the art” about a topic of interest to pretty much everyone who takes care of horses (which is why they hold the lecture in a very big room). Dr. Dyson’s topic was “Equine Lameness: Clinical Judgment Meets Advanced Diagnostic Imaging.”

Now I’ve got to admit that this subject is near and dear to my heart, mostly because of two unrelated thoughts.

- Medicine advances, and it’s important to keep up with those advances

- I think that it’s not prudent to pay for something unless you have a good idea what you’re going to get, and that what you’re going to get is going to make a difference

The first half of the lecture focused on evaluation of lame horses, as well as the anesthetic injections that we use to assist in lameness evaluations. That hour-and-a-half can be pretty well summed up as:

The first half of the lecture focused on evaluation of lame horses, as well as the anesthetic injections that we use to assist in lameness evaluations. That hour-and-a-half can be pretty well summed up as:

- You often have to be very, very thorough and careful in your examination of lame horses, particularly if it’s not an obvious problem, because if you aren’t you’re going to miss something, or make a poor diagnosis.

- Anesthetic blocks often block a whole lot more than we think they block because the anesthetic doesn’t necessarily stay where you put it. Which can lead to mistakes.

The second half of the lecture focused on diagnostic techniques used in the evaluation of equine lameness – especially Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI), and, secondarily, what we can do about the problems that are discovered with MRI, and particularly problems of the foot. So, here’s a summary of the second half of the lecture.

- We can see a whole lot of things that we never knew about when you take an MRI of a horse

- Many (most?) lameness evaluations don’t require MRI

- None of the new treatments for the lameness problems that Dr. Dyson described can be shown to do anything

So let’s break this down a bit, because:

So let’s break this down a bit, because:

- You, as the horse owner, are the one who is expected to pay for MRI, and other techniques

- You, as the horse owner, are the one who is expected to pay for all of these new treatments

- I think that it’s not prudent to pay for something unless you have a good idea what you’re going to get (I started off with that one, but I figure it’s worth repeating)

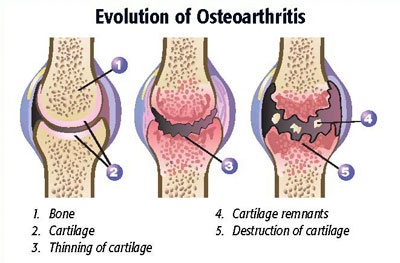

If you want to know more about what MRI is, you can CLICK HERE to learn about it (and other fancy diagnostic machines). MRI has revolutionized the diagnosis of many conditions in human medicine, and the technique has been very successfully applied to horses over the past decade or so. MRI is especially useful for helping to sort out problems that occur in the horse’s foot, which, as it turns out, is a pretty complicated anatomical package – there are many, many structures in the horse’s foot that can be injured in many, many ways. You can see all sorts of things when you image a horse’s foot with an MRI, and, as time passes, we’re even starting to understand a good bit more about what those things are.

ASIDE: One thing that’a a bit problematic about detailed imaging is that the ability to see usually is pretty far in advance of the understanding of what is being seen. Take microscopes. Antony van Leeuwenhoek (you pronounce it) invented the first microscopes. He looked at all sorts of things under his revolutionary devices – he just didn’t know what he was seeing. So, for example, in 1683, he did scrapings of his mouth, and the mouths of his wife and his daughter, (who, in a disgusting historical aside – never cleaned their teeth in their lives), and found, “I then most always saw, with great wonder, that in the said matter there were many very little living animalcules, very prettily a-moving. The biggest sort. . . had a very strong and swift motion, and shot through the water (or spittle) like a pike does through the water.” All very good and colorful, of course, but the fact of the matter is that he had no idea what he was seeing. It took a lot of time to figure it all out.

MRI in horses is sort of like that. Happily, finally, some people are starting to get pretty good at figuring out what we’re seeing. What we can do about what we see, well, that’s another kettle of fish.

So…. onwards. Dr. Dyson’s second point was that most horses don’t need an MRI. Many lame horses get better with a little bit of time. Other imaging modalities are often more useful. Now this may come as a bit of a revolutionary thought to those that have taken their horses to clinics that own an MRI, but, according to Dr. Dyson, an MRI should not necessarily be a routine tool used for lameness evaluation. Machines can’t tell you everything. Plus – and this is my comment – you have to pay for them.

So…. onwards. Dr. Dyson’s second point was that most horses don’t need an MRI. Many lame horses get better with a little bit of time. Other imaging modalities are often more useful. Now this may come as a bit of a revolutionary thought to those that have taken their horses to clinics that own an MRI, but, according to Dr. Dyson, an MRI should not necessarily be a routine tool used for lameness evaluation. Machines can’t tell you everything. Plus – and this is my comment – you have to pay for them.

So here’s the last point that Dr. Dyson made – and I want you to read this carefully, all the while holding onto your purse or wallet…

The “new” treatments available for horses – PRP, stem cells, Tildren® and the like – can’t be shown to do anything.

Remember what I said at the start of this, about Dr. Dyson being a meticulous record keeper? Well, as it turns out, just about the worst thing that you can do, insofar as “promising” treatments go, is to actually follow-up and see what happens to the horses that get the treatments. As long as you deliver a treatment with a lot of hope and optimism, and don’t follow up to see what actually happened, there’s no reason to stop promoting a treatment. But if you start actually following up to see what happens to the horses after they get treated, sometimes hope and optimism turn out of have been the only thing that have been purchased.

Dr. Dyson has followed up on many horses that have been treated for ligament problems in the hoof with stem cells, platelet rich plasma (PRP), shock wave, and others. So far, the modalities haven’t been shown to do anything of benefit, that is:

Dr. Dyson has followed up on many horses that have been treated for ligament problems in the hoof with stem cells, platelet rich plasma (PRP), shock wave, and others. So far, the modalities haven’t been shown to do anything of benefit, that is:

- They haven’t shortened the time it takes for the horse to recover, that is, they haven’t made more horses recover any more quickly than just giving the time to heal, and

- They haven’t made the horses recover better, that is, at the end of the day, there is no improvement in the quality of the tissue that repaired the injury

Other than that…

She’s looked specifically at Tildren®. I haven’t written about Tildren® yet, but suffice it to say that it’s touted as something of a miracle drug. If you live in the US, it can currently only be imported from overseas – if you live overseas, you can get it more easily, even if your horse doesn’t ultimately benefit from it. From what I read, it’s used for just about any condition that may involve a horse’s bones; otherwise stated, people will dump it in a horse to treat just about anything. Dr. Dyson carefully documented 12 horses with disease of the navicular bone (the condition for which the drug has been approved in Europe). She carefully followed up on them. Her results? Of the 12 horses treated, exactly zero of them have benefited from the drug. That’s 0 for 12, which, if I remember my math, is not a very good average.

My takeaway from Dr. Dyson’s lecture is that you should be very clear about what you want when you get your horse evaluated for lameness. Indiscriminately using that newest technologies and treatments you might that you spend a whole lot of money to end up in the same place, at the same time, as you would have if you had just waited a bit. And, frankly, I think that’s was a very important message.

My takeaway from Dr. Dyson’s lecture is that you should be very clear about what you want when you get your horse evaluated for lameness. Indiscriminately using that newest technologies and treatments you might that you spend a whole lot of money to end up in the same place, at the same time, as you would have if you had just waited a bit. And, frankly, I think that’s was a very important message.

If you’re interested, here are links to a few abstracts on equine lameness by Dr. Dyson:

Comparison between magnetic resonance imaging and histological findings in the navicular bone of horses with foot pain: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22494146

Magnetic resonance imaging and histological findings in the proximal aspect of the suspensory ligament of forelimbs in nonlame horses: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21649714

High-field magnetic resonance imaging investigation of distal border fragments of the navicular bone in horses with foot pain: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21492207