One of the interesting things about being in veterinary practice for a while is that you get to see things come, go, and change. New diseases pop up from time to time, we develop technologies that allow us to diagnose things that we didn’t know existed, and medicine changes, accordingly.

One of the interesting things about being in veterinary practice for a while is that you get to see things come, go, and change. New diseases pop up from time to time, we develop technologies that allow us to diagnose things that we didn’t know existed, and medicine changes, accordingly.

Unfortunately, medicine can be a bit faddish. That is, when a new diagnosis or diagnostic technology comes along, everyone becomes extremely vigilant, and all of a sudden many cases get diagnosed, when no cases were ever diagnosed before. New diseases become sensations to the equine magazines, veterinary publications, forums, and conferences, too. Add in what’s been called “disease creep,” that is, the feeling that every new sensation or action that a horse has or takes is a disease symptom that warrants a medical test or treatment (come to think of it, I’m going to have to write an article on that), and pretty soon you’ve got a whole industry built up around a single problem, whether the problem actually exists, or not.

Enter EPM.

When I got out of veterinary school, pretty much nobody had ever head of EPM. That, of course, doesn’t mean that it never happened: in fact, it probably did. It’s just that nobody knew what it was. Sometime in the 1970’s, veterinarians started to figure it out, but it wasn’t until the 1980’s, or early 1990’s, that it started to get a ton of publicity. Then, we all started to hear about this weird disease of the horse’s nervous system called EPM. And the disease took flight.

So let’s stop here for a second and briefly talk about how the disease works. It’s caused by a protozoa, which is responsible not only for the disease, but also for the “P” part of EPM. Protozoa are one-celled organisms, more complicated than bacteria, and that’s really all you need to know, but you can find out more about them if you’re interested, or if you’re simply preparing to go on Jeopardy®, if you CLICK HERE. And if you do want to be a contestant on Jeopardy, CLICK HERE.

So let’s stop here for a second and briefly talk about how the disease works. It’s caused by a protozoa, which is responsible not only for the disease, but also for the “P” part of EPM. Protozoa are one-celled organisms, more complicated than bacteria, and that’s really all you need to know, but you can find out more about them if you’re interested, or if you’re simply preparing to go on Jeopardy®, if you CLICK HERE. And if you do want to be a contestant on Jeopardy, CLICK HERE.

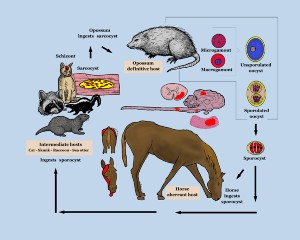

But I digress. Normally, this protozoa – most EPM infections are caused by one called Sarcocystis neurona, although there are others – passes pretty happily between opossums and raccoons (mostly) and birds (mostly) and you’d never really know that it was there at all except for the fact that the protozoa sometimes ends up where it’s not supposed to be: like the horse’s spinal cord. I’m not really going to discuss the life cycle; I mean, it’s interesting, but really, all you want to know is if your horse has EPM, and what to do about it. But if you really do want a lot of detail, CLICK HERE for the USDA site, which is a good site, because, for among other reasons, they’re not trying to sell you anything. Plus, the drawings are nice, one of which is reproduced right next to this paragraph.

Of course the “E” in “EPM” stands for equine. The “M” is for myeloencephalitis, which simply means inflammation of the spinal cord and brain. Taken together, you’ve got Equine Protozal Myeoloencephalitis – EPM. One thing you can be sure of is that where there’s myeloencephalitis, there are going to be some really weird clinical signs. The brain and spinal cord do weird and mysterious things normally, and things can get even weirder when the system gets infected.

And thus, the problems.

Back when veterinarians first started recognizing the disease, it wasn’t difficult to diagnose at all (in fact, some people still think it’s easy to diagnose, but it’s not, and saying that it is easy is dumb, but more on that in a bit). The reason it was easy to diagnose was because, at the time, all you had to do was draw a blood test (called a Western blot test). If your horse had some sort of weird clinical sign – just about any sort of weird clinical sign, from stumbling to in-coordination to muscle loss to you name it – and he had a positive blood test, voilà, he got treated for EPM. In fact, EPM was a virtual oasis for weird horse problems, because if a horse was doing something weird, and he had a positive blood test, at least you had an answer. In that way, EPM was sort of a diagnosis for the diagnostically destitute. Add in that you could treat your newly diagnosed horse (for months), and many of those horses got better, and you had a very satisfying scenario, as long as you didn’t worry about the fact that many horses do get better from many things, as long as you wait for months.

And all was good. For a while.

After a few years of doing blood tests, it started to dawn on folks that 50-60-70-80% of all horses in some parts of the US had a positive blood test. This, of course was pretty perplexing, because most of these horses were clinically normal. And that meant that either 1) Lots and lots of horses were sick, and nobody had ever realized it, or 2) Something was wrong with the test. Turns out, it was the test.

You see, many horses were getting and are getting exposed to the organism that causes EPM via contaminated feed. Opossums and and raccoons love to eat – and poop in – horse feed, as it turns out, and it’s that poop that spreads the organism around. So, it turns out that most horses, when exposed to the protozoa simply mount an immune response to it, and that’s that. You can measure the immune response, which is what the blood test was doing. That’s all it was doing – and horses mount immune responses, whether they actually get infected, or not.

BUT THERE’S GOOD NEWS HERE: That being, if you’re worried about your horse having EPM, and his blood tests are negative for EPM, the chances are he doesn’t have the disease. At least it’s something.

BUT THERE’S GOOD NEWS HERE: That being, if you’re worried about your horse having EPM, and his blood tests are negative for EPM, the chances are he doesn’t have the disease. At least it’s something.

Unfortunately, as the name of the disease says, in some horses, the parasite ends up in the spinal canal. There’s fluid in there, and veterinarians started to tap into the horse’s spinal canal to get that fluid. As it turns out, infected horses mount an immune response that can be measured in the spinal fluid. So that helps – some. Unfortunately, it’s also fairly easy to contaminate the spinal fluid when you get a sample, and even a few drops of blood can mess up the whole process. Even so – the best way to accurately diagnose EPM at the moment is to take blood and spinal fluid, and compare the results. But because so many horses get exposed, relative to how many horses get sick, and because it’s pretty easy to contaminate samples, even the most accurate tests aren’t necessarily definitive for the disease.

The problem with things being difficult is that lots of people can’t do difficult things. Taking fluid from the horse’s spinal canal falls on the more difficult side of veterinary procedures. That’s one reason why although you may see lots of people running around saying they’ll float your horse’s teeth, there’s no similar parade of equine spinal tappers. So, given that getting spinal fluid is hard, people still worry about EPM, and people like answers, some people have started doing one of two things. They:

- Come up with easy ways to make a diagnosis

- Treat and see what happens

As for number one, if you’ve read my columns long enough, you’ve probably come across one of my favorite sayings, by the late H.L. Mencken, that for every complex problem, there’s a solution that’s simple, easy, and wrong. So it is with EPM. Taking a blood test was easy – relying on positive results to come up with a diagnosis turned out to be wrong.

One of the most simple and most particularly wrong ways to diagnose EPM is by touching the “acupuncture points.” Putting aside the fact that as wise as the ancient Chinese may have been, they weren’t diagnosing EPM, and the fact is that there’s no credible evidence that acupuncture points exist as distinct entities, the idea that you, or your barn manager, or some interested third party can make an easy diagnosis of a complex and still-not-completely understood problem by poking around on your horse’s hind end is just, well, dumb. Of course, the fact that something is dumb doesn’t preclude some people from doing it – and certainly won’t stop some people from adding comments about this article to my Facebook page – but dumb it is. There are even youtube videos about how to do it – and they’re dumb, too. In fact, even though pretty much every single person who knows anything about EPM also knows that the idea of making an EPM diagnosis by poking around on a horse’s rear end is dumb. In fact, the idea has even been studied: and there’s nothing to it (CLICK HERE to read the study).

Now, for number two. The “treat and see what happens” approach makes some sense on some level, at least if you’re not concerned about wasting time and lots of money. But with EPM, the whole thing has gotten a bit out of hand. Now, if a horse isn’t acting right – maybe he isn’t swapping his hind leads perfectly ever time, or he snorts when there’s a full moon – what the heck, he could have EPM. I mean, EPM is sort of weird, and the horse is acting weird, so…diagnosis made!

Now, for number two. The “treat and see what happens” approach makes some sense on some level, at least if you’re not concerned about wasting time and lots of money. But with EPM, the whole thing has gotten a bit out of hand. Now, if a horse isn’t acting right – maybe he isn’t swapping his hind leads perfectly ever time, or he snorts when there’s a full moon – what the heck, he could have EPM. I mean, EPM is sort of weird, and the horse is acting weird, so…diagnosis made!

The problem with this approach is that lots of things get better over time. So, if after months of treatment, your horse stops snorting at the moon, you can’t possibly know if it was the treatment or not. You could very well be fretting – and annoying the heck out of your horse by treating – for nothing. And that’s not even bringing up the innumerable bogus supplements that are out there, none of which have been shown to do anything for or against EPM.

What about prevention? Glad you asked. I’m a big fan of the “ounce of prevention worth a pound of cure” line of thinking. Even though there’s no vaccine (it’ll be hard to make one, too, because, for among other reasons, EPM does not appear to be a failure of the horse’s immune system), there are some things you can do.

Try to keep varmints out of your horse’s feed. Use sealed containers. Keep the feed room door closed. That sort of thing.

Try to keep varmints out of your horse’s feed. Use sealed containers. Keep the feed room door closed. That sort of thing.- Keep feeders and waterers clean (which you should want to do anyway, right?).

- Get rid of dead critters on your property, because opossums and raccoons eat them, and dead critters may carry the organism (especially birds).

- Keep feeding areas clear, at least as best as you can, to try to keep the varmints away from the barns, feed rooms, and shelters.

EPM is a serious disease. Fortunately, most horses don’t have it. In fact, due to geographic factors – climate, lack of hosts, etc. – it’s almost unheard of in some areas. For example, it’s almost unheard of in southern California, for example, where horses aren’t kept in any sort of a farm-like setting. It doesn’t occur in most parts of the world under any circumstances: many horses simply can’t get EPM. And it seems that the majority of the horses that do get exposed to the organism fight it off before it gets into their spinal cords. But, like I said, since EPM is sort of a weird disease, when horses start acting weird (or at least not in the way that an owner or trainer had hoped), there are lots of weird things currently being done in both diagnosis and treatment.

If you suspect that your horse is having a problem that could be associated with EPM, I’d suggest that you approach things very carefully. Make sure that you’re getting good advice from people with some real knowledge. Coming up with a proper diagnosis isn’t easy, and it may well be worth your while to work with an internal medicine specialist, or a veterinary neurologist if your veterinarian isn’t comfortable with getting spinal fluid to help confirm a possible diagnosis.

If you suspect that your horse is having a problem that could be associated with EPM, I’d suggest that you approach things very carefully. Make sure that you’re getting good advice from people with some real knowledge. Coming up with a proper diagnosis isn’t easy, and it may well be worth your while to work with an internal medicine specialist, or a veterinary neurologist if your veterinarian isn’t comfortable with getting spinal fluid to help confirm a possible diagnosis.

It’s a curious disease, EPM. And people’s responses to it can be, well, curious.