Ethics in horse medicine has always been a topic that is near an dear to my heart, starting when I was sophomore veterinary student at Colorado State University, and took a class with my friend, the late Dr. Bernie Rollin. I’ve been invited to give a talk and conduct an afternoon session on ethics at the American Association of Equine Practitioners (in December 8, 2013), I’ve served on the Ethics Committee of the AAEP, and I have a chapter on ethics in equine medicine in a book being published on Veterinary Ethics this year (with Dr. Barry Kipperman of UC Davis, and Bernie as co-editors). Ethics is a topic that gets a lot of discussion, but it’s also one that, when push comes to shove, sometimes gets shoved into the back, especially when it comes to giving horses treatments. Ethics can be a hard row to hoe.

NOTE: For those of you that love words and expressions – like I do – that’s an agricultural expression that goes back to at least 1818, when fields were tilled by hand, with a hoe, talking about how hard something is. It’s “row” not “road.”

Ethics is an old philosophical field, that fundamentally is just the study of right and wrong behavior. Pretty simple concepts actually – but they can be very difficult to apply in practice.

One of the easiest ways that you can make somebody mad at you is to call him or her unethical. And, when someone does something that is marginally ethical, the defense is often something like, “Everyone has their own ethics.” And, even though the phrase is grammatically incorrect (it should be “his or her” own ethics), it’s undoubtedly true. Still while that may be true, the fact is that some ethics are better than others. Duh, I suppose, but practices that are kinder, fairer, and more honest are generally more ethical than practices that are more mean-spirited, unfair, or untruthful. Everybody should strive for ethical practices, but especially veterinarians, since we’re supposed to be the experts in horse health care, and because we want people to trust us.

One of the easiest ways that you can make somebody mad at you is to call him or her unethical. And, when someone does something that is marginally ethical, the defense is often something like, “Everyone has their own ethics.” And, even though the phrase is grammatically incorrect (it should be “his or her” own ethics), it’s undoubtedly true. Still while that may be true, the fact is that some ethics are better than others. Duh, I suppose, but practices that are kinder, fairer, and more honest are generally more ethical than practices that are more mean-spirited, unfair, or untruthful. Everybody should strive for ethical practices, but especially veterinarians, since we’re supposed to be the experts in horse health care, and because we want people to trust us.

People who are perceived as being more ethical – kinder, fairer, etc. – are generally thought more highly of than are folks that aren’t. So, for example, in surveys of professions, nurses are generally up near the top, because 1) They’re thought of as honest and 2) They do so much for other people. On the bottom end of the scale tend to be folks like lawyers, used car salesmen, and US Congressmen; all folks who are thought to be in it mostly for themselves. Veterinarians tend to rate up near the top of the scale, too, but that can easily change (and apparently has, at least in some circles, judging by the comments I get on some of my posts).

One of the things that makes ethical discussions so complex is that there are so many parties who have an interest in what happens to horses. In an ideal world (which, if you didn’t know, we’re not living in) the best ethical conduct benefits everybody. However, if people aren’t ethical – if they are perceived as doing bad things to horses – pretty soon society will do something about it. For example, no matter what someone might think about it, the new Horse Racing and Integrity Act of 2020 was conceived precisely because lots of people in society felt that not enough was being done to protect racehorses.

It would be a lot easier being a veterinarian if you could just do what is best for the horse, and not charge anyone a fee for doing it (owners would like that, too). But the fact is, veterinary medicine is a business, and I couldn’t sit here at my desk typing if I didn’t also make some money seeing horses (unless this writing thing were to somehow take off – but I’d probably still see horses, because I enjoy being around them so much). I don’t think anyone begrudges anyone the right to make a living, and veterinarians do have an ethical obligation to try to take care of themselves and their families. But if all a person does is think about oneself – when it comes to ethics, and business – it’s pretty easy to justify blurring ethical lines so more money can be made. The fact that veterinarians profit from what they sell is – or at least should be – an important ethical consideration; in fact, it’s a huge ethical problem, in some circles. Which gets back to why being ethical is important, because people don’t mind paying for something, they just don’t like feeling like they’ve been taken advantage of. If you do the right thing by the horse, usually everything works out OK.

Many veterinarians like to think of themselves like pediatricians, you know, taking care of a patient while someone else is making decisions and paying the bills. But that’s not necessarily the case; one reason is because there’s no force of law behind what a veterinarian does. Heck, people don’t even have to use veterinarians. But ethical conduct is one good reason why people might be inclined to use veterinary services, so it’s really smart for veterinarians to be ethical.

Many veterinarians like to think of themselves like pediatricians, you know, taking care of a patient while someone else is making decisions and paying the bills. But that’s not necessarily the case; one reason is because there’s no force of law behind what a veterinarian does. Heck, people don’t even have to use veterinarians. But ethical conduct is one good reason why people might be inclined to use veterinary services, so it’s really smart for veterinarians to be ethical.

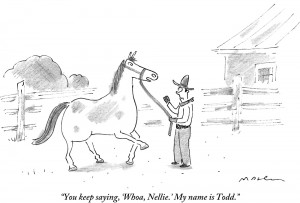

One of the biggest ethical problems facing veterinarians is when their ethical obligations conflict with the clients’ wishes. For example, some clients may be looking for things like “increased performance” so that they can get a ribbon, or belt buckle, or some other prize. Veterinarians may get in an ethical bind by trying to do things to and for those horses so that they can satisfy the client. It’s a really tough situation sometimes, and there aren’t any easy answers. Sometimes it’s damned if you do – damned if you don’t. Don’t do what the client wants, and risk losing the client. Alternatively, do what the client wants, pocket the money, and forget about the horse. It can be nearly impossible to practice ethically in an unethical environment. Money tends to pollute ethics – it has, after all, has been widely credited as being the root of all evil.

The veterinarian’s ethical responsibility to him- or herself, and to the horse, should ideally come before the demands of the client. Otherwise stated, a veterinarian shouldn’t do what he or she doesn’t feel is right. In fact, while doing what the client wants may increase satisfaction, at least short term, in human medicine, trying to work to make the client happy is associated with worse outcomes and greater costs.

The veterinarian’s ethical responsibility to him- or herself, and to the horse, should ideally come before the demands of the client. Otherwise stated, a veterinarian shouldn’t do what he or she doesn’t feel is right. In fact, while doing what the client wants may increase satisfaction, at least short term, in human medicine, trying to work to make the client happy is associated with worse outcomes and greater costs.

PLEASE NOTE: That means that if all you worry about is being happy, you can very easily be spending a lot more money than you need to, even though it doesn’t do the horse any good. But you can always find someone to sell you something, even if you don’t need it.

Working on the ethical borderline carries a good bit of risk. I mean, if someone is unethical enough to ask that a veterinarian do something that isn’t in the horse’s best interest, it’s not like that person is all of a sudden going to support the veterinarian if something goes wrong. Plus, for the veterinarian, saying that he or she was doing was what the client requested isn’t a good legal defense – the laws assume that the veterinarian is working for the good of the horse.

Unless people who work around horses (including veterinarians) give society a reason to listen to them, society is going to do whatever it wants. Society’s interest in horses has resulted in things like federal laws against “soring” of horses. Ignore ethical treatment of horses, and you get things like the State of New York taking over horse racing (I gave numerous examples). Under any circumstances, it’s pretty hard to argue that people shouldn’t do everything that they can to make sure that horses are treated as well as possible. If they don’t, society will step in.

In today’s world, there are also lots of folks who aren’t veterinarians who say that they can do important things for horses. If veterinarians sell the same stuff that the other folks do, there’s really very little from which to distinguish them. I mean, who is to say that a veterinarian that says that he or she is doing “chiropractic” on horses is better or worse than a chiropractor (DC – Doctor of Chiropractic), who actually went to school to do chiropractic?

PLEASE NOTE – I AM NOT DISCUSSING THE MERITS OF CHIROPRACTIC IN THIS ARTICLE.

Ethics, in addition to sound scientific research, and education (special knowledge, as it were) are really about the only things that distinguish veterinarians from other folks that want to take care of horses. If veterinarians don’t act ethically – heck, if anyone doesn’t try to do the right thing by the horse – they’re giving up something special.

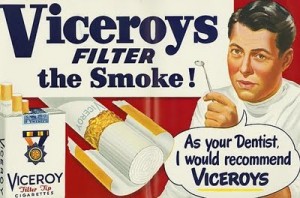

One troubling ethical question that’s dear to my heart is the ethics of providing treatments. Simply stated, it is unethical to promote therapies based on criteria that aren’t relevant to the likelihood of a successful outcome. Otherwise stated, if someone is trying to persuade you to use something for your horse because it’s…

One troubling ethical question that’s dear to my heart is the ethics of providing treatments. Simply stated, it is unethical to promote therapies based on criteria that aren’t relevant to the likelihood of a successful outcome. Otherwise stated, if someone is trying to persuade you to use something for your horse because it’s…

- New

- Natural

- Holistic

- Not “Western” Medicine

- Cutting Edge

- Ancient

- Etc., etc., etc.

… that person is quite possibly acting unethically, because none of those things has anything to do with whether or not the treatment actually helps the horse. If a treatment or therapy is just an expensive way to mine money out of your purse or wallet, that’s just not right.

There were many other points in my talk that I haven’t covered – I mean, it was a 50 minute talk, and I’m trying to keep this at 1500 words or so. You can see the PowerPoint (PDF) presentation if you CLICK HERE, and I’ll put up the full article as soon as it is available. If you find something in the slide presentation that interests you, ask, and I’ll expand on it. But maybe the subject of ethics and horse medicine will provide some food for thought. I mean, seriously, can you really make a good argument against trying to do what’s best for the horse?

There were many other points in my talk that I haven’t covered – I mean, it was a 50 minute talk, and I’m trying to keep this at 1500 words or so. You can see the PowerPoint (PDF) presentation if you CLICK HERE, and I’ll put up the full article as soon as it is available. If you find something in the slide presentation that interests you, ask, and I’ll expand on it. But maybe the subject of ethics and horse medicine will provide some food for thought. I mean, seriously, can you really make a good argument against trying to do what’s best for the horse?