You’ve decided to sell your horse and the potential buyer has sent a veterinarian to your stables to perform a prepurchase exam. Or, you’re the buyer, and you’re excited to complete your purchase. As you stand, beaming with satisfaction, the veterinarian picks up the horse’s left front leg. Bending it at the fetlock, he or she holds it in the air for 60 seconds or so, releases the limb, and asks that the horse be immediately jogged down the drive. In astonishment, you watch as the horse that you’ve known – or hoped – to be sound moves off with an obvious bob of the head. He’s most decidedly lame after the test. What happened? What does it mean?

You’ve decided to sell your horse and the potential buyer has sent a veterinarian to your stables to perform a prepurchase exam. Or, you’re the buyer, and you’re excited to complete your purchase. As you stand, beaming with satisfaction, the veterinarian picks up the horse’s left front leg. Bending it at the fetlock, he or she holds it in the air for 60 seconds or so, releases the limb, and asks that the horse be immediately jogged down the drive. In astonishment, you watch as the horse that you’ve known – or hoped – to be sound moves off with an obvious bob of the head. He’s most decidedly lame after the test. What happened? What does it mean?

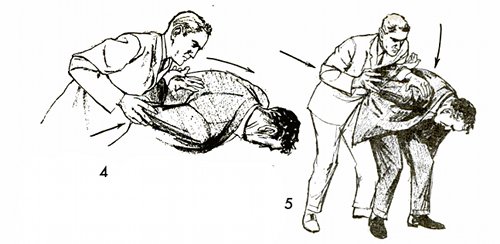

What you have witnessed is a phenomenon not necessarily of the veterinarian’s creation, but something that can sometimes occur following a procedure called a forelimb flexion test. In a forelimb flexion test, various joints and soft tissue structures of the lower limb are stretched and/or compressed for a brief period of time by bending the limb. Afterward, the horse is immediately trotted off and observed for signs of lameness.

Simple, really. But it gets messy.

Forelimb flexion tests were described in Swedish veterinary literature as early as 1923. And, since then, they’ve become something of an integral part of the evaluation of the lame horse. But not only that, forelimb flexion tests are generally routinely included in prepurchase evaluations of horses intended for sale.

The test is not unlike what you might experience if someone asked you to sit in a crouch for sixty seconds and then run right off. Usually – and especially if you’ve never had knee problems – you can run off just fine, particularly after a couple of steps. If you’ve never had a problem, chances are that you’re fine, no matter what happens in those first couple of steps. But very occasionally, that stiffness and soreness that you might feel could signal a problem (such as a bad knee).

This test used to make me nuts, and to some extent, it still does. That’s because I’m often not to sure what to make of the state of things when a horse takes some bad steps after a flexion test. I mean, I know I might not pass such a test. So who’s to say that every horse should? Because of that question, back in 1997, I did I study. It’s still timely. Let me tell you about it.

This test used to make me nuts, and to some extent, it still does. That’s because I’m often not to sure what to make of the state of things when a horse takes some bad steps after a flexion test. I mean, I know I might not pass such a test. So who’s to say that every horse should? Because of that question, back in 1997, I did I study. It’s still timely. Let me tell you about it.

In my study, I looked at fifty horses (100 legs) of various breeds, ages, sex, and occupation. The owners were gracious enough to let me explore my curiosity about forelimb flexion tests. The horses were from my practice, an included a wide variety of pleasure and performance horses – including some world class jumping horses – but overall, they were a representative sampling of all of the horses that were in my practice.

I took a lameness history of all of the horses in the study, and I watched them trot and lunge on hard ground, and I felt their legs for abnormal swellings or areas of soreness. If a client’s horse was lame, or showed some obvious physical abnormality, I didn’t use him – I just wanted to study sound horses. And then I did two tests – a “normal” (for me) flexion test, and a test that was as hard as I could flex the leg without the horse going up in the air and trying to kill me (for my study, I held the horse’s leg up in the air for 60 seconds, but there’s no agreement on the “proper” amount of time – which is another problem). I recorded the responses. In addition, I took X-rays all of the lower legs of the horses.

I took a lameness history of all of the horses in the study, and I watched them trot and lunge on hard ground, and I felt their legs for abnormal swellings or areas of soreness. If a client’s horse was lame, or showed some obvious physical abnormality, I didn’t use him – I just wanted to study sound horses. And then I did two tests – a “normal” (for me) flexion test, and a test that was as hard as I could flex the leg without the horse going up in the air and trying to kill me (for my study, I held the horse’s leg up in the air for 60 seconds, but there’s no agreement on the “proper” amount of time – which is another problem). I recorded the responses. In addition, I took X-rays all of the lower legs of the horses.

I examined the horses again 60 days later. If an individual horse incurred some lameness in the 60-day period following the initial examination, the lameness was correlated with clinical, flexion test, and X-rays findings.

It was a LOT of work.

Here’s what I found.

I found that forelimb flexion tests couldn’t tell me anything about the future of a sound horse. I could make every single horse lame with a hard enough flexion test, with the exception of one particularly annoying Arabian gelding who was always trying to bite me (no Arabian jokes, please).

I found that forelimb flexion tests couldn’t tell me anything about the future of a sound horse. I could make every single horse lame with a hard enough flexion test, with the exception of one particularly annoying Arabian gelding who was always trying to bite me (no Arabian jokes, please).- Horses that had “something” on their X-rays weren’t any more likely to be lame after a “normal” flexion test than horses that had “clean” X-rays.

- Horses that had positive “normal” flexion tests weren’t any more likely to be lame 60 days out, either (those horses that were lame mostly had things like hoof abscesses, which nobody could have predicted anyway).

- If you follow a groups of horses for 60 days, there’s a decent chance that a few of them might experience an episode of lameness. Who knew?

So what did I conclude? Well, I said – right there in front of an entire meeting of the American Association of Equine Practitioners – that I didn’t think that it was a good idea to rely on forelimb flexion tests to make a diagnosis of some current or future problem without some other supporting sign. I said I didn’t think that they were very sensitive, or that they were very specific. And I said that I didn’t think it was a good idea to turn a horse down base solely on a response to a forelimb flexion test, either.

Which caused a bit of a kerfuffle.

But I still feel the same way. That is:

But I still feel the same way. That is:

- Flexion tests appear to also have no predictive value for the occurrence of forelimb lameness for at least 60 days after you do the flexion test.

- Otherwise stated, if a previously sound horse goes lame after a flexion test, the lameness could not have been reasonably predicted by forelimb flexion.

Some folks apparently feel that there is a potential for hurting a horse with forelimb flexion tests. They may be concerned that by flexing the joint, one could apply sufficient stress to the tissues to injure them. I couldn’t find any sign of such a thing in the horses I looked at, and I flexed them really hard. They did a study on flexion tests in Belgium a couple of decades back, in which horses were subjected to as many as six flexion tests a week, and that didn’t cause any problems for the horses, either.

What’s the Bottom Line?

If you’re a seller, I don’t think that you need to be overly concerned if your otherwise sound horse takes a few lame steps after a forelimb flexion test. There are just too many variables. For example:

- Older horses are more likely to be positive to flexion that are younger horses

- The longer you hold a limb in flexion, the more likely the horse is to take a few lame steps afterwards

- Men tend to flex more firmly than do women

- The same horse may have different responses to flexion tests on different days

If you’re a buyer, don’t be too eager to walk away from a horse that you otherwise like just because he takes a few lame steps after a flexion test. You have to consider a lot of other factors, such as whether you like the horse, or whether he does what you want him to do, or if he’s a color that you like.

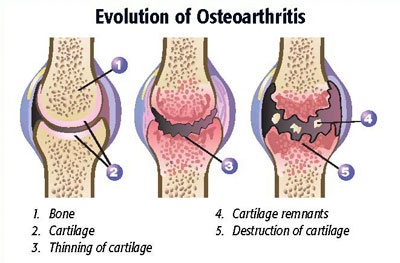

You just can’t consider the forelimb flexion test in a vaccum. It has to interpreted in light of clinical findings such as fluid in the joint, reduced limb or joint flexibility, pain to palpation, or clinical lameness in the limb that demonstrates the positive response. If you see abnormal X-rays findings (such as osteoarthritis) in a limb that has a positive response to a flexion test, that may add some significance, and particularly if there is concurrent clinical lameness. However, to keep things confusing, my study also found that many radiographic abnormalities occur in clinically sound horses. Remember, you have to ride the horse – you can’t ride the radiographs. Horses can and do perform well for a variety of riding endeavors even when they do not perform well on a forelimb flexion test.

You just can’t consider the forelimb flexion test in a vaccum. It has to interpreted in light of clinical findings such as fluid in the joint, reduced limb or joint flexibility, pain to palpation, or clinical lameness in the limb that demonstrates the positive response. If you see abnormal X-rays findings (such as osteoarthritis) in a limb that has a positive response to a flexion test, that may add some significance, and particularly if there is concurrent clinical lameness. However, to keep things confusing, my study also found that many radiographic abnormalities occur in clinically sound horses. Remember, you have to ride the horse – you can’t ride the radiographs. Horses can and do perform well for a variety of riding endeavors even when they do not perform well on a forelimb flexion test.

If a horse does respond to forelimb flexion test – on a prepurchase exam or a lameness exam – don’t just stop there, especially if he’s otherwise OK. Further examination of the horse is likely warranted. Look for other signs of a problem, such as lameness, loss of limb flexibility or a painful response to palpation and/or manipulation of the area that you suspect may be a problem. Follow-up with X-rays. With a complete examination, you will likely receive the answer you need. As for a positive response to a forelimb flexion test, it may just be that everything is OK, but the horse doesn’t like his leg bent up!