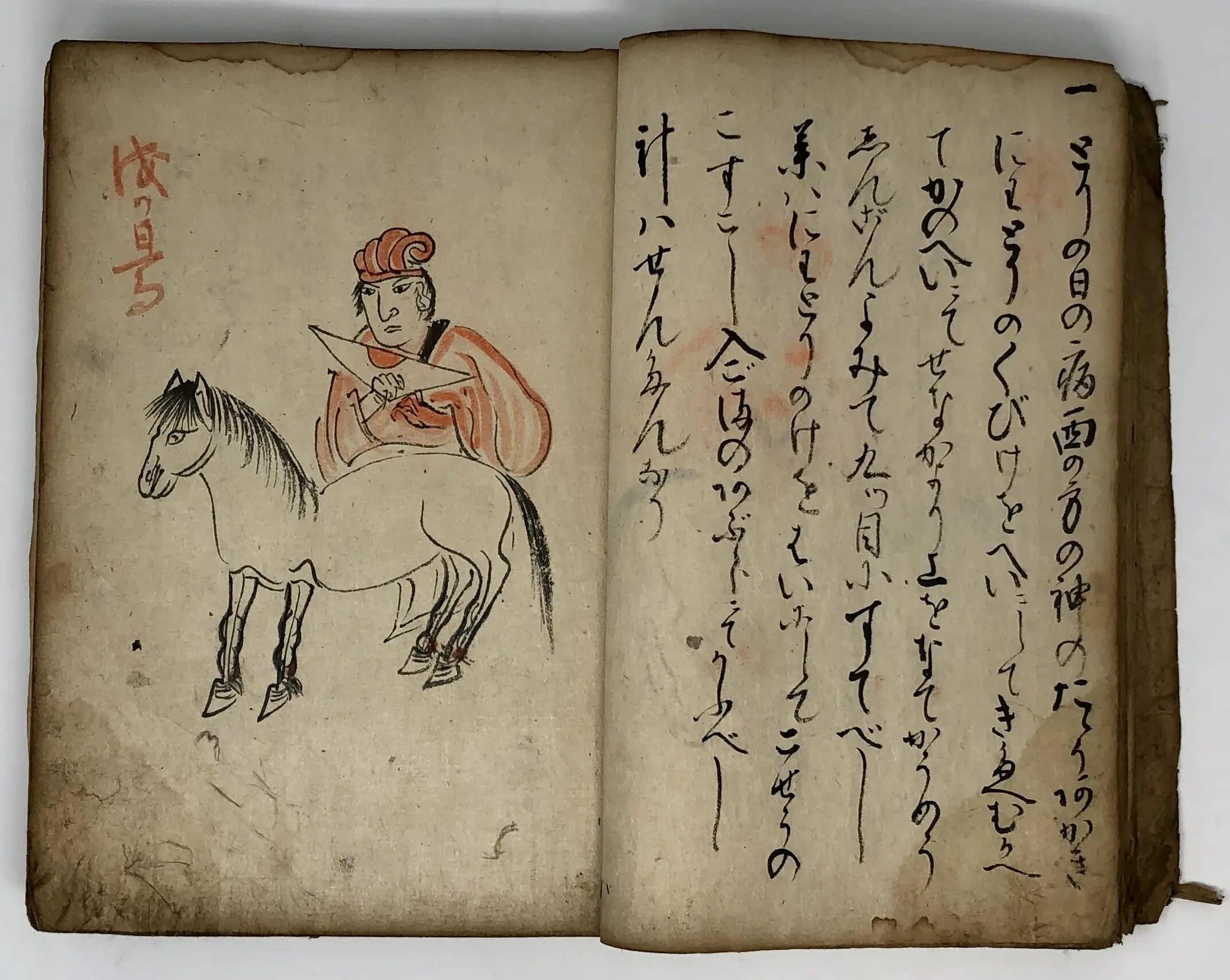

A few years back, I started writing a book based on a manuscript about a particular type of old Japanese horse medicine that I received in Kyoto. The book’s going to the printer in Italy soon (if all goes according to plan), and although it doesn’t have any treatments that would seem to be especially helpful for the horses of today, it still provides some interesting insights for today’s horse owner, I think: history often does.

A few years back, I started writing a book based on a manuscript about a particular type of old Japanese horse medicine that I received in Kyoto. The book’s going to the printer in Italy soon (if all goes according to plan), and although it doesn’t have any treatments that would seem to be especially helpful for the horses of today, it still provides some interesting insights for today’s horse owner, I think: history often does.

Here’s one of my favorite treatments from 17th century Japan. The condition for which the horse is being treated can’t be identified – honestly, it seems that at this time in history, in this particularly place in the world, an underlying cause was never really identified. Only the practitioner knows when this treatment is to be employed.

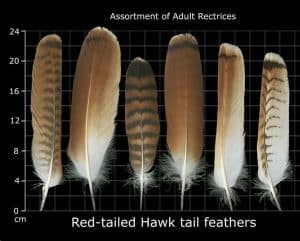

Get as many hawk feathers as you can. Tie them onto the end of a stick. Rub the stick up and down the horse’s back three times. Throw the stick in the river.

Now, by way of a somewhat tongue-in-cheek disclaimer, this treatment should not be taken as medical advice, at least in the US, if for no other reason than, in most cases, collecting feathers of native North American birds in the United States is illegal under the Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918 (MBTA), and you should probably always consult with your veterinarian prior to instituting any treatment on your horse. Government regulations notwithstanding, I’m pretty sure that if rubbing hawk feathers up and down a horse’s back was an effective treatment for anything, there’d probably be a pretty vigorous market, regardless. But I digress. That’s also not my point. My point is that there are lots of parallels between what passed for horse medicine over 400 years ago in Japan, and what is being passed in some circles as horse medicine today.

Now, by way of a somewhat tongue-in-cheek disclaimer, this treatment should not be taken as medical advice, at least in the US, if for no other reason than, in most cases, collecting feathers of native North American birds in the United States is illegal under the Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918 (MBTA), and you should probably always consult with your veterinarian prior to instituting any treatment on your horse. Government regulations notwithstanding, I’m pretty sure that if rubbing hawk feathers up and down a horse’s back was an effective treatment for anything, there’d probably be a pretty vigorous market, regardless. But I digress. That’s also not my point. My point is that there are lots of parallels between what passed for horse medicine over 400 years ago in Japan, and what is being passed in some circles as horse medicine today.

SECRET SOCITIES

In the 17th century Japan, horse care was the purview of families or groups who had “special knowledge” about horses. This was passed around and shared among the group, but the knowledge really wasn’t intended for anyone else (in fact, one old Japanese manuscript that I have does note on the cover that the information inside was to be kept secret). And that’s sort of just like things are today. We have veterinarians, but we also have chiropractors and body workers and massage therapists and “Traditional Chinese Medicine” practitioners (who, curiously, as not practicing according to the historical veterinary practices of China – CLICK HERE if you want to read more) and laser therapists and pulsating magnetic field therapists and… well, all sorts of people who claim to have some sort of special insight into the treatment of horses. Of course, some of those claims are better supported by science – see especially those made by veterinary medical science – but that’s another very important discussion.

In the 17th century Japan, horse care was the purview of families or groups who had “special knowledge” about horses. This was passed around and shared among the group, but the knowledge really wasn’t intended for anyone else (in fact, one old Japanese manuscript that I have does note on the cover that the information inside was to be kept secret). And that’s sort of just like things are today. We have veterinarians, but we also have chiropractors and body workers and massage therapists and “Traditional Chinese Medicine” practitioners (who, curiously, as not practicing according to the historical veterinary practices of China – CLICK HERE if you want to read more) and laser therapists and pulsating magnetic field therapists and… well, all sorts of people who claim to have some sort of special insight into the treatment of horses. Of course, some of those claims are better supported by science – see especially those made by veterinary medical science – but that’s another very important discussion.

When a person is perceived as having secret knowledge, that person may also be perceived as something of an authority. And that sets up an interesting relationship that the authority gets to take advantage of (for better or worse). That’s why, for example, when the doctor tells you take off your pants, you generally comply, but in other settings – say at a restaurant or play – you’d (hopefully) be less inclined to acquiesce to the same request. Thus, 400 years ago, in Japan, if the doctor said get a bunch of hawk feathers, you’d probably start hunting for them right away.

ASIDE: In today’s world, the person attending the horse might just happen to have a supply of hawk feathers that he or she would be happy to sell you. Which is a whole ‘nother can of worms.

ASIDE: In today’s world, the person attending the horse might just happen to have a supply of hawk feathers that he or she would be happy to sell you. Which is a whole ‘nother can of worms.

CURIOUS IDEAS

In 17th century Japan, it becomes obvious (hopefully) that the horse doctors really didn’t know much about what they were treating. The idea that disease might be related to anatomy, or that some microorganism might be able to make a big horse sick, was almost completely unknown. In 17th century Japan, the doctors didn’t really examine the horse at all – at least, not in the sense of providing some sort of detailed analysis of the horse’s physical condition – they prescribed according to cosmology. Such mundane things as the horse’s temperature or pulse rate were not things with which the doctors could be bothered. Nevertheless, they forged confidently ahead. In fact, hawk feathers were just one of many treatment options in 17th century Japan.

www.savagechickens.com

It’s like that today, too, at least sometimes. It’s a fact that we don’t know everything about horses and horse diseases, but instead of admitting that sometimes we just don’t know what the problem is, or what can really be done about it, people keep coming up with unique ideas on how to treat horses. Perhaps your horse has bones “out of place” or something is “out of alignment.” Maybe he has some mysterious energies that need to be influenced or redirected. Perhaps there are some magic (stem) cells you can inject into him that will do whatever it is that you want them to do.

Honestly, there’s really nothing wrong with new and curious ideas per se. But if all you have to offer is curiosity – without any real evidence of results or good evidence of effectiveness – eventually, like hawk feathers, your treatments become a historical curiosity. There’s a long history of that sort of thing in horse medicine, even in the fairly recent past.

SINCERE RITUAL

There’s a ritual associated with the practice of any kind of medicine, and it’s very important. When you think about it, there’s a good bit of ritual in the way that medicine (not only horse medicine) is practiced now. The (horse) doctor comes. He or she takes out various instruments, implements, and tools, and gives injections of this, that, or the other, often after carefully preparing the area to be injected… it’s all done just so. You’re probably impressed, at least to some degree. The ritual sets up a relationship. That’s not to say that medicine is ONLY ritual – at least it’s not supposed to be – but there are rituals in medicine, nonetheless, and they are very important.

There’s a ritual associated with the practice of any kind of medicine, and it’s very important. When you think about it, there’s a good bit of ritual in the way that medicine (not only horse medicine) is practiced now. The (horse) doctor comes. He or she takes out various instruments, implements, and tools, and gives injections of this, that, or the other, often after carefully preparing the area to be injected… it’s all done just so. You’re probably impressed, at least to some degree. The ritual sets up a relationship. That’s not to say that medicine is ONLY ritual – at least it’s not supposed to be – but there are rituals in medicine, nonetheless, and they are very important.

Rituals carry symbolic meanings and help define the relationship between the veterinarian and the client. Rituals help legitimatize the doctor, and help give meaning to what he or she does. Unfortunately, sometimes it’s hard to say whether the rituals are based on good evidence (for example, the ritual cleaning of the skin before you cut into it to do surgery is very important), or whether they’re just done out of habit, sentiment, or because, “That’s the way we do it.” Nevertheless, the ritual aspects of healing are very powerful, at least psychologically. And they’ve been that way since, oh, probably forever.

THE HORSES GOT BETTER

When it comes to try to assist in the healing of biological systems like the horse, I’m pretty sure that, given the propensity of biological systems to try to heal themselves, the lack of an effective treatment Is not always a problem. For example, if a horse has a colic, and the colic is mild, sometimes the biggest challenge for the veterinarian is to get there before the horse gets better on its own so that the veterinarian can take the credit. It’s always worked that way, I think. So, for medical conditions – I don’t have an exact number, but it’s been estimated that it’s something along the lines of 80% of them – as long as the attending therapist doesn’t do anything to directly mess things up, the patient is probably going to turn out OK. CLICK HERE to read my article about the 80:15:5 rule.

When it comes to try to assist in the healing of biological systems like the horse, I’m pretty sure that, given the propensity of biological systems to try to heal themselves, the lack of an effective treatment Is not always a problem. For example, if a horse has a colic, and the colic is mild, sometimes the biggest challenge for the veterinarian is to get there before the horse gets better on its own so that the veterinarian can take the credit. It’s always worked that way, I think. So, for medical conditions – I don’t have an exact number, but it’s been estimated that it’s something along the lines of 80% of them – as long as the attending therapist doesn’t do anything to directly mess things up, the patient is probably going to turn out OK. CLICK HERE to read my article about the 80:15:5 rule.

PLEASE NOTE: That does not mean that 80% of every individual condition will get better. If a horse has a serious leg fracture, leaving it along won’t do any good. But taking all medical conditions as a whole, a surprising number of them will get better all by themselves.

A HISTORICAL TAKE-HOME

What does all this imply for the hawk-feather-wielding practitioner in 17th century Japan? Well, honestly, it probably means that most of the time, he will have been perceived as having done some good (not necessarily for hawks, of course). Most of the time, the fact that he spent some time trying to come up with an effective treatment based on some “secret knowledge” that his society possessed would have inspired hope and confidence in the horse owner, who would have cared enough about the horse to have called the practitioner. The solemnity and ritual with which the hawk feathers might have been rubbed would have been impressive, and would have also instilled some confidence, at least initially, I’m sure.

What does all this imply for the hawk-feather-wielding practitioner in 17th century Japan? Well, honestly, it probably means that most of the time, he will have been perceived as having done some good (not necessarily for hawks, of course). Most of the time, the fact that he spent some time trying to come up with an effective treatment based on some “secret knowledge” that his society possessed would have inspired hope and confidence in the horse owner, who would have cared enough about the horse to have called the practitioner. The solemnity and ritual with which the hawk feathers might have been rubbed would have been impressive, and would have also instilled some confidence, at least initially, I’m sure.

We see the exact same things going on today, be it with acupuncture, shock wave, lasers, magnets, manipulations, PRP, stem cells, or any number of other treatments. We’re relatively poorly armed in the fight against disease. New treatments are certainly needed. But, if history serves as a teacher – and it usually does – most of them will just end up being hawk feathers.