As you know, if you follow the Feed Rules, the number one rule is that the majority of your horse’s diet has to be made up of plant material (forage).

However, unless your horse lives out in a big pasture (or the Mongolian steppe), chances are that your horse doesn’t have constant access to growing plants. And even if he does have access to growing plants, that may not be a great thing, because, unlike those Mongolian horses, who walk around all day on thousands and thousands of acres eating relatively poor quality grass (and whatever), a horse in limited pasture just sits there and eats grass, and gets fat, and can develop all sorts of problems like laminitis. Thus, either for caloric reasons (no pasture) or to provide fiber (for those in pasture) you’re most likely going to have to provide your horse with some sort of dried plant product: most commonly, of course, that would be hay.

For some reason, some people seem to get very emotional about their horse’s hay. There’s no question that there are pluses and minuses for each type of hay, and people can get very opinionated about it, if for no other reason than it’s been around for thousands of years. For example, there are records of alfalfa hay being fed to horses from around 500 BCE, so you’d think if alfalfa hay was all that awful (as some may assert), someone might have figured it out by now. But, when you think about it, hay (which comes from an old German word, hewi, referring to “that which is mowed”) has pretty much allowed for horses to be domesticated. I mean, if you’re going to ride and work horses, you can very well go chasing them about the Mongolian steppe all day, right? They’re faster than you are.

Depending on where you live, you’re going to have access to any one of a number of hays, from alfalfa to timothy, from coastal bermuda (another hay whipping boy – more on that in a bit) to lucerne, and orchard, and birdsfoot trefoil (what a name), and any number of others, including teff hay (one of the newer entries in the hay field, at least in the US).

The fact of the matter is that if plants can be dried, they can usually be fed to horses. In fact, in Japan a few hundred years ago, they fed dried pea plants to horses. Now it’s certainly true that there can be a considerable amount of variability in hay – depending on the time that it was cut, conditions under which it was dried, etc. – but hays also all have a lot of things in common. They all provide the horse with things like protein, fiber, energy, vitamins and minerals, albeit in varying amounts, but – and here’s the kicker – almost always in amounts that satisfy the normal horse’s dietary requirements.

So lets start breaking this down.

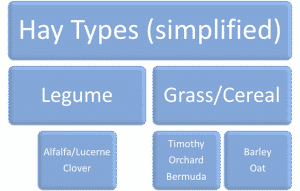

Even though there are lots of different hays, they can all be roughly divided into two types. Legumes are plants that have microorganisms associated with their root systems. Alfalfa hay is the classic legume (lucerne hay, which is pretty much the same thing, is another). Hays made from grasses and cereal grains (such as barley or oat) make up the second group. By the way, Teff hay – originally a plant grown in Ethiopia for feeding people – is a relatively new entry in the grass group, and you can read about it if you CLICK HERE.

The great thing about hay is that you can make a great diet for horses using either type of hay as the foundation of the diet. That said, there are some differences, so here goes. In general, when you compare them to legume hays, grass and cereal grain hays have:

1. Less protein (but plenty of protein for adult horses)

2. Less calories (which means you might have to feed more hay if you’re feeding a grass hay than you would if you fed a legume hay). The fact that grass hays have fewer calories than alfalfa hays on a per weight basis makes them great for horses that need to diet, because you can feed the horse the same weight of hay, but also give fewer calories, and still fill up your horse’s stomach. It’s sort of like filling up on shredded wheat vs. ice cream – they both get you full, but it’s a lot harder to get fat eating shredded wheat.

2. Less calories (which means you might have to feed more hay if you’re feeding a grass hay than you would if you fed a legume hay). The fact that grass hays have fewer calories than alfalfa hays on a per weight basis makes them great for horses that need to diet, because you can feed the horse the same weight of hay, but also give fewer calories, and still fill up your horse’s stomach. It’s sort of like filling up on shredded wheat vs. ice cream – they both get you full, but it’s a lot harder to get fat eating shredded wheat.

3. Less calcium (but plenty of calcium for adult horses)

4. Fewer vitamins (but plenty of vitamins for adult horses)

5. More digestible fiber (but legumes have plenty of fiber, too)

So, what does this mean?

The higher protein, calcium, and calorie content of legume hays make them excellent for feeding to young horses, because young, growing horses, need extra calories and protein. The extra protein, calcium and  calories pose absolutely no danger to older horses, but you might find that if you feed your adult horse too much alfalfa, and you don’t give him enough exercise he’ll get fat (by the way, in case you didn’t know, this too-many-calories and not-enough-exercise thing can be a problem in people, too).

calories pose absolutely no danger to older horses, but you might find that if you feed your adult horse too much alfalfa, and you don’t give him enough exercise he’ll get fat (by the way, in case you didn’t know, this too-many-calories and not-enough-exercise thing can be a problem in people, too).

How much hay should you feed your horse? A rough guideline for an adult horse that’s not in heavy work is 1.5% – 2% of his body weight. That means for a horse that weighs 1000 pounds (say, your average Quarter horse), you’d be looking at feeding 15 – 20 pounds of hay per day. If you work him, he may need more calories, which usually means either more hay, or, more calories from somewhere else.

And here’s a money-saving tip! If you get a feed scale, and weigh the hay (as opposed to measuring it in, say, “flakes”), you’ll save money, because you won’t waste so much hay. Feed scales are also a great way to make sure your horse is getting the right amount to eat if somebody else is feeding your horse (you can say, “Give him 7 pounds of hay,” instead of “a flake” of hay, for example).

You can do a lot of things with the plants that make hay after you dry them. People will chop them up, and mix them with molasses (for example, “A&M” is alfalfa and molasses), steam press them into little cubes, or dice them finely and press them into pellets. All of these products can provide good nutrition for horses, and none of them are as bad as people try to make them out to be.

A QUICK NOTE ON HAY PRESERVATIVES: Drying is a way to preserve the plants from which hay is made. But sometimes – not very often, really – growers use hay preservatives in an effort to prevent mold, or in an effort to get the hay cut and baled before the rains come in. Still, producers of horse hay don’t routinely use preservatives because they aren’t economical. As a routine harvesting procedure, good quality hay is almost always put up without using a preservative. Even so, there’s no indication whatsoever that hay preservatives are harmful. So, if a hay ad says that the hay is “preservative free,” it probably is, but all the rest of it probably is, too.

A QUICK NOTE ON HAY PRESERVATIVES: Drying is a way to preserve the plants from which hay is made. But sometimes – not very often, really – growers use hay preservatives in an effort to prevent mold, or in an effort to get the hay cut and baled before the rains come in. Still, producers of horse hay don’t routinely use preservatives because they aren’t economical. As a routine harvesting procedure, good quality hay is almost always put up without using a preservative. Even so, there’s no indication whatsoever that hay preservatives are harmful. So, if a hay ad says that the hay is “preservative free,” it probably is, but all the rest of it probably is, too.

A CARROT FOR YOU ANALYTICAL TYPES: While most horses get along just fine with a couple flakes of hay twice a day, some owners get very concerned about precision. That’s all fine, but if you really want to be precise, there are a few things to consider. One of the first thing is that it matters where your horse’s hay comes from – the hay from a field in Oregon may be quite different from that grown on a Colorado mountain plateau. Most horses get fed feed that is grown pretty close to where they live, and what’s in your horse’s feed is directly affected by the soil properties, soil management practices, and harvesting procedures. You can usually get information about the nutritional content of various hays, and typical management practices from an agricultural extension agent, or a regional agricultural college.

A NOTE FOR YOU NON-ANALYTICAL TYPES: Most of the time, hay that looks good and smells good will be good for your horse. If your horse looks good and feels good, it’s most likely because you’re doing something right.

But back to analytics, keep in mind that even if you want to go to the time and expense to do nutrient analysis, it’s only as good as the sample you take. A handful from one bale is not necessarily going to be representative of the entire stack. And there’s some laboratory variability, too. And if you’re not running a big operation, if you’re buying a few bales of hay from one hay supplier, and a few more from another, there is really no point in doing a nutrient analysis, because that hay is going to be gone before you get the results back. But you’re not necessarily without analytic hope there, either.

But back to analytics, keep in mind that even if you want to go to the time and expense to do nutrient analysis, it’s only as good as the sample you take. A handful from one bale is not necessarily going to be representative of the entire stack. And there’s some laboratory variability, too. And if you’re not running a big operation, if you’re buying a few bales of hay from one hay supplier, and a few more from another, there is really no point in doing a nutrient analysis, because that hay is going to be gone before you get the results back. But you’re not necessarily without analytic hope there, either.

If you like doing analyses, and you’re comfortable with averages, then you might want to look at the website for Equi-Analytical Laboratories (CLICK HERE). In addition to information about sampling, they’ve got a link to “Common Feed Profiles” at the top of their homepage, and the tables provide all sorts of nutritional information that you can use to get some idea of the nutritional content of your horse’s ration. It’s the sort of thing that you can go nuts over, really.

OH, ABOUT BERMUDA GRASS

If you regularly consult Dr. Google, you’ll find that some people assert that Bermuda Grass hay is associated with an increased incidence in a particular type of colic: impaction of the ileum. As near as I can tell, that assertion is based on a study of 78 horses, conducted over 14 years (CLICK HERE to read an abstract of the study). While the study notes that hay quality may be a factor – most caring people (not just experts) would recommend feeding good quality hay to your horse – there are a couple of facts to keep in mind. First is that Bermuda Grass hay is one of the more commonly fed hays, at least to horses in the United States. Second is that ileal impactions themselves are not particularly common. I think it’s probably a much better idea to feed a horse good quality Bermuda Grass hay than a poor quality anything else.

The bottom line, when it comes to feeding hay? Feed a good quality hay (no dust, no mold, lots of green color). Don’t worry too much about what kind of hay you’re feeding, because horses can do very well on all sorts of different hays. Feed hay in proper amounts, and don’t let your horse get fat (make sure you can feel his ribs). If you do those few simple things, you’ll go a long way towards making sure that your horse is as healthy as – well – as healthy as a horse!

The bottom line, when it comes to feeding hay? Feed a good quality hay (no dust, no mold, lots of green color). Don’t worry too much about what kind of hay you’re feeding, because horses can do very well on all sorts of different hays. Feed hay in proper amounts, and don’t let your horse get fat (make sure you can feel his ribs). If you do those few simple things, you’ll go a long way towards making sure that your horse is as healthy as – well – as healthy as a horse!