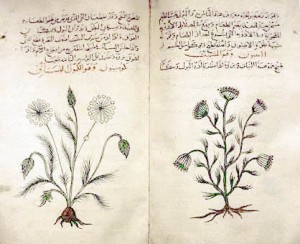

Pages from an ancient Arabic herbal medicine book

The history of veterinary applications of plants – today mostly referred to by such terms as “herbals” and “botanicals” – is quite long and well documented. Given all that’s known and been published, it’s also a bit curious that it’s a source of so much misinformation. That’s interesting, too!

QUICK NOTE: That fact that plants have been used as medicine since pretty much for as long as anyone can tell seems to be responsible for at least some of the appeal of plants as medicines. The line of thinking is along the lines of, “Well, if it’s been around for so long, then there must be something to it.” Of course, when you look at things that way, you’d be able to make a very persuasive argument for riding donkeys to work, but I digress.

Back to history. Black and white hellebore (Helleborus niger and Veratrum album, respectively) was pierced through the ear of horses or sheep by the Roman physician Pliny in the 1st century AD. In the early 20th century hellebore was used as a purgative, emetic, anthelmintic and parasiticide, Which was great, I guess, but it also caused death in many animals (which, while killing the parasite, was probably not the result that most who give anti-parasitic agents are looking for). You can find historical prescriptions for plant-based medications in just about every society, from such diverse sources as the Chinese Yuan Heng liaoma ji (arguably the most famous of the Chinese veterinary texts) to the medicinal practices of the natives of the North American plains. Botanical “horse medicines” were provided during the American Civil War. Even as late as 1957, popular books continued to list such substances as aconite, belladonna, cinchone, ipecac, nux vomica (strychnine) and tobacco for veterinary use. While I’ve been practicing for a while, learning about plants wasn’t a big part of my veterinary education, with the exception of those – quite a few actually – that are poisonous. I’ve gone on to learn quite a bit (you’re not supposed to stop learning, right?).

A gift from nature

ANOTHER QUICK NOTE: Given all of that’s known about poisonous plants, t seems not to occur to some people that plants are perhaps something less than, “Nature’s Gift®,” at least sometimes That is, some plants are really not very healthy for horses at all. One has to pick one’s spots, I suppose.

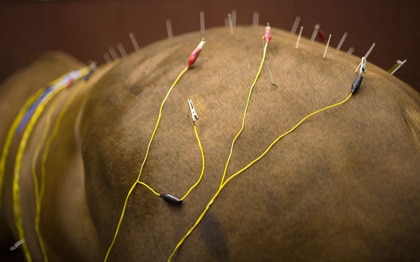

Anyway, since the mid-20th century, veterinarians didn’t really receive any education in the use of plants as medicine, probably for many reasons (read on). It wasn’t until the “alternative” medicine movement of the late 20th century that interest in the use of plants as medicine was revived in industrialized societies (even as they were still quite commonly used in less developed areas where things like medicine, hygiene, and fresh water still haven’t had significant inroads into society and, as such, are pretty much not available).

MEDICINAL PLANTS = CRUDE DRUGS

We should all be able to agree that plants at least have the potential to act as medicine. But if they do, it has to be because there’s something in them, right? (If not, I’d love to hear your thoughts.) The fact is that the active ingredients of some pharmaceuticals are identical to, or are derivatives of, bioactive constituents of historic folk remedies. Furthermore, herbal and botanical sources are the origin of as much as 30% – 35% of all modern pharmaceuticals, and lots of people continue to actively look for substances in plants that might also have medicinal effects.

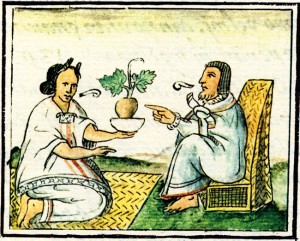

Here’s a good example of a drug in/from a plant. You know aspirin (acetylsalicylic acid), right? Aspirin is a derivative of salicylic acid, which, as salicin (salicyl alcohol plus a sugar molecule), occurs in the flower buds of the meadowsweet (spirea) and in the bark and leaves of several trees, notably the white willow (Salix alba). Over time – centuries, actually – some cultures – those to which white willow trees were available – figured out that white-willow-bark extracts could be used as a pain remedy. Here’s another example. The natives of the tropical Andean forests of South America figured out that quinine, derived from the bark of the Cinchona tree, was an anti-fever agent. As such, it was widely employed by them for the treatment of fevers of virtually any origin, and its “discovery” by western explorers started an entire industry, one that declined only when modern medicines were developed. The “Fever Bark Tree” was also the subject of a fascinating book, which is well worth the read, if you can find it.

Here’s a good example of a drug in/from a plant. You know aspirin (acetylsalicylic acid), right? Aspirin is a derivative of salicylic acid, which, as salicin (salicyl alcohol plus a sugar molecule), occurs in the flower buds of the meadowsweet (spirea) and in the bark and leaves of several trees, notably the white willow (Salix alba). Over time – centuries, actually – some cultures – those to which white willow trees were available – figured out that white-willow-bark extracts could be used as a pain remedy. Here’s another example. The natives of the tropical Andean forests of South America figured out that quinine, derived from the bark of the Cinchona tree, was an anti-fever agent. As such, it was widely employed by them for the treatment of fevers of virtually any origin, and its “discovery” by western explorers started an entire industry, one that declined only when modern medicines were developed. The “Fever Bark Tree” was also the subject of a fascinating book, which is well worth the read, if you can find it.

YES, BUT….

There’s a reason that the use of plants as medicines went into decline. You see, if one simply wants to assert that herbal products were used throughout history, one may also overlook some real problems. Many herbal remedies simply didn’t do anything. But let’s say that you’re bound an determined to get your salicin from white willow bark. In order to ingest one gram of salicin from willow bark – which is only about half as potent as aspirin – you have to ingest at least fourteen grams of the bark. If you’re not a big fan of eating bark, that could be problematic in and of itself, but willow bark also has lots of tannins in it. Tannins are astringent (drying), bitter tasting compounds found in many plants (think red wine grapes). The tannins in willow bark – and the salicin itself, for that matter – are very irritating to the stomach. So, while consuming 14 grams of white willow bark might get you an effective medicine, it would also most likely give you quite a bellyache.

YOU’RE NOT ALWAYS SURE WHAT YOU’RE GETTING

Another significant problem with herbs as medicines is that there is a lot of natural variation in plants. Different species of the same plant may have active compounds of varying qualities and quantities. Plants aren’t stable, either – in fact, the potency of plant-based compounds deteriorates (just like everything), but at unknown rates. And, of course, different compounds also have various absorption rates from the gastrointestinal tract. Oh, and there are also variations from batch to batch – and even plant to plant – depending on growing conditions. I don’t usually mind surprises, but I’m less enthusiastic about surprises when the surprise is supposed to be a medicine.

Another significant problem with herbs as medicines is that there is a lot of natural variation in plants. Different species of the same plant may have active compounds of varying qualities and quantities. Plants aren’t stable, either – in fact, the potency of plant-based compounds deteriorates (just like everything), but at unknown rates. And, of course, different compounds also have various absorption rates from the gastrointestinal tract. Oh, and there are also variations from batch to batch – and even plant to plant – depending on growing conditions. I don’t usually mind surprises, but I’m less enthusiastic about surprises when the surprise is supposed to be a medicine.

WHAT, ANOTHER QUICK NOTE? Yes. Imagine going to the grocery store and being asked to buy a product that you 1) Don’t know what’s it contains, 2) Don’t know how long it will last, and 3) Don’t really know what it’s supposed to do. But it is in a pretty package. Well?

HISTORICAL USE VS. CURRENT USE OF PLANTS

Another of the curious things about the use of plants as drugs is how much differently they are used today than they were in times past. It’s a bit disingenuous to rely on the the “plants have been used for thousands of years” line of thinking when today, plants are being used quite differently from those glorious days of yesteryear. Historically, herbs were used in smaller amounts, as specific treatments for disease (rather than prophylactically, that is, in order to prevent health problems), in crude form (as opposed to enriched extracts) and not in association with other synthetic medications (today, people often combine plants and pharmaceuticals, but that just raises concerns about interactions between herbs and drugs, at least concerns in people that care about such things).

Another of the curious things about the use of plants as drugs is how much differently they are used today than they were in times past. It’s a bit disingenuous to rely on the the “plants have been used for thousands of years” line of thinking when today, plants are being used quite differently from those glorious days of yesteryear. Historically, herbs were used in smaller amounts, as specific treatments for disease (rather than prophylactically, that is, in order to prevent health problems), in crude form (as opposed to enriched extracts) and not in association with other synthetic medications (today, people often combine plants and pharmaceuticals, but that just raises concerns about interactions between herbs and drugs, at least concerns in people that care about such things).

Also, in historical terms, it’s often hard to know what condition plants were being used to treat. Centuries back, the indications for using a given botanical were poorly defined, because, well, pretty much nobody know what they were treating. I mean, when’s the last time you ever heard of a case of “dropsy,” or the ever popular “mallendars and sallendars” which afflicted horses in the 17th century? In addition to not really knowing what they were treating, folks that used plants as medicines didn’t really know what they were giving, either. Plant dosages were arbitrary – unavoidably so, actually – because the concentrations of the active ingredient were unknown.

SO WHAT DID THEY ACTUALLY SAY IN THE HISTORY BOOKS?

Well, there’s a problem. You can’t even use history as a reliable guide to what was being used, because there weren’t reliable methods of identifying plants, either as to genus or species. Now that really didn’t seem to matter much to historical societies, because society was willing to accept a great deal of risk in the treatment of disease. I mean, they couldn’t really treat much of anything effectively, so if the patient died as a result of treatment, well, that was something that could be tolerated. If they didn’t, the treatment got the credit (sort of like today, actually).

Well, there’s a problem. You can’t even use history as a reliable guide to what was being used, because there weren’t reliable methods of identifying plants, either as to genus or species. Now that really didn’t seem to matter much to historical societies, because society was willing to accept a great deal of risk in the treatment of disease. I mean, they couldn’t really treat much of anything effectively, so if the patient died as a result of treatment, well, that was something that could be tolerated. If they didn’t, the treatment got the credit (sort of like today, actually).

It’s not as if the historical record is detailed or complete anyway. The transmission of information throughout history was pretty haphazard (no internet, although that certainly has its own problems). Most folks couldn’t read. Literate herbalists copied extensively from one another over millennia, and then they mixed accurate (by modern standards) information with nonsense, misconceptions and inaccuracies. So, you see, in reality, even with the best of intentions, it may not be possible to use the historical record as a guide for many of the currently advocated uses of herbal and botanical products.

BUT DID THEY WORK?

Well, not so’s you’d notice. The historical record is also rather sobering when it comes to considering the question of whether herbal and botanical products are effective medicines. Historically, herbal and botanical medicines were not responsible for any measurable improvement in human health. In 1900, human life expectancy was 45 years; however, by 1996 it was 76.1 years. These dramatic changes were largely due to clean water, vaccination and the ability to control infections via pharmacology, and not due to a lack of plants.

Well, not so’s you’d notice. The historical record is also rather sobering when it comes to considering the question of whether herbal and botanical products are effective medicines. Historically, herbal and botanical medicines were not responsible for any measurable improvement in human health. In 1900, human life expectancy was 45 years; however, by 1996 it was 76.1 years. These dramatic changes were largely due to clean water, vaccination and the ability to control infections via pharmacology, and not due to a lack of plants.

Then there’s this thorny question. When discussing the historical efficacy of herbal medications, you have to ask. “Effective compared to what?” Historical medical treatments were often horrible, and including such gems as bleeding, or prescribing large doses of mercury salts. Plus, they didn’t work (although doctors kept using them). So one might imagine that a botanical product that didn’t kill a person immediately or make them sick or bloody might be thought of rather fondly in some circles, especially when compared to the alternatives.

Even at that, in the past, the emphasis for the of plants was on the treatment of symptoms, rather than underlying disease conditions (which had yet to be identified). “Success” was measured by elimination of the symptom, rather than elimination of the underlying problem. So, for example, if a fever went away after ingesting willow bark, the treatment would have been said to have “worked,” even though the disease process that caused the fever might have continued on, unaffected by the treatment.

SUMMING IT UP

Using the historical record to advocate herbal medications really doesn’t work. There weren’t any effective alternatives to plants, and people had little idea about the true causes of disease. Today, most of the herbs that have significant potential for good (or harm) have been abandoned by the herbal industry. Those are the plants that are used to make real medicines. People are still looking, too.

Using the historical record to advocate herbal medications really doesn’t work. There weren’t any effective alternatives to plants, and people had little idea about the true causes of disease. Today, most of the herbs that have significant potential for good (or harm) have been abandoned by the herbal industry. Those are the plants that are used to make real medicines. People are still looking, too.

ONE FINAL NOTE

History is great – but don’t use it as a reason to try plants to treat a horse’s medical problems. If you find this stuff as fascinating as I do, check out my chapter in the book, “Veterinary Herbal Medicine” (CLICK HERE), or any of several excellent articles by Dr. Ryan Huxtable, Emeritus Professor of Pharmacology at the University of Arizona (CLICK HERE for one).