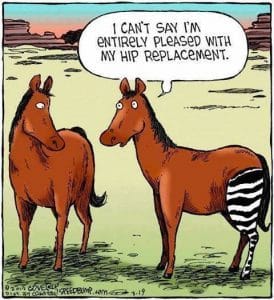

One of the real fears every equine practitioner (well, to be honest, just about anyone who chooses to take care of other living things) is that something will go wrong. Unfortunately, sometimes things do go wrong – it’s inevitable when dealing with a living system. No matter how careful one is, no matter how closely one follows proper procedures, things can go wrong. Which can sometimes lead to hard feelings. And malpractice suits.

One of the real fears every equine practitioner (well, to be honest, just about anyone who chooses to take care of other living things) is that something will go wrong. Unfortunately, sometimes things do go wrong – it’s inevitable when dealing with a living system. No matter how careful one is, no matter how closely one follows proper procedures, things can go wrong. Which can sometimes lead to hard feelings. And malpractice suits.

SINCE THIS IS GOING TO COME UP…

You probably want to know if I’ve ever been sued for malpractice. The answer is, “Yes.” One was due to a pre-sale exam. The horse, an upper level jumping horse, went lame 2 ½ years after he was purchased, after a very long and active show career. The lameness was creatively to be construed to be my fault. The case was thrown out before it ever got to court. One was when an old horse was said to be older than I said he was. When he was purchased, I said he was probably in his mid-teens – 7 years alter someone else said he as in his mid-20’s. I had noted on the exam that aging a horse by its mouth isn’t accurate and is just an estimate – that didn’t go anywhere, either. Regardless of their merits, these cases cause a lot of anxiety and expense. That’s why I hope I can help you try to avoid them.

BACK TO THE QUESTION AT HAND

BACK TO THE QUESTION AT HAND

We (veterinarians) generally carry insurance to protect us against malpractice suits. Malpractice insurance is a way to protect yourself and your family. Lawsuits can be devastating – emotionally, financially, and professionally – and malpractice insurance brings protection and, to some extent, peace of mind.

Periodically the American Veterinary Medical Association sends out advice on how to protect oneself against malpractice suits. They have some rather specific advice that any good practitioner will tend to follow. In fact, I just got a list of items in the mail. I read through it carefully and the list got me thinking.

As much as veterinarians don’t want to do malpractice, and as much as we want to be protected, my just-a-wild guess is that people who own horses don’t want malpractice done to their horses, either. So, in reading over my “What to Do to Help Prevent Malpractice Suits’ list, I decided to turn it around, looking at it from the point of view of people who are trying to protect themselves and their horses. Here’s what I came up with.

BEFORE TREATMENT

- Make sure you ask about the risks to your horse before you allow anything to be done to him.

- Ask about other options besides what has been recommended, especially if something invasive is being proposed.

Make sure you completely understand what is being done before you let it be done.

Make sure you completely understand what is being done before you let it be done.- Sign a consent form before you allow a significant procedure to be done and get a copy of the form. You probably don’t need to worry about this if you’re getting your horse dewormed – a major surgery or some sort of experimental injection procedure is another matter entirely.

- If someone tells you that he or she is a specialist, find out what that really means. In veterinary medicine, the term, “specialist” is explicitly reserved for veterinarians who have been certified by one of the colleges of veterinary specialists (as I remember, there are 22 of them). There are veterinary specialists in surgery, neurology, dermatology, radiology, and 18 others. On the other hand, terms like “Podiatrist” and “Chiropractor” are not recognized as veterinary specialties; they can be (and are) used by just about anyone, regardless of training. Dentistry is a recognized specialty, however, as I’ve said before, there are many people who call themselves “equine dentists” who are not and routine dental care of the horse should not require advanced specialty degrees.

QUICK ASIDE: The point that I’m trying to make here is that if someone tells you that they are a “specialist,” find out what that really means. If someone asserts that they are a “specialist,” and they’re really not, well, be careful. Many of the “specialists” in the horse world don’t carry insurance, either, meaning if something happens, you may not have much recourse. Of course, you could not worry about it. Still, it is your horse.

QUICK ASIDE: The point that I’m trying to make here is that if someone tells you that they are a “specialist,” find out what that really means. If someone asserts that they are a “specialist,” and they’re really not, well, be careful. Many of the “specialists” in the horse world don’t carry insurance, either, meaning if something happens, you may not have much recourse. Of course, you could not worry about it. Still, it is your horse.

- If you’re concerned that there may be better options than you’re being provided, or that there may be someone better suited to do a procedure, ask for a second opinion or a referral.

- If you’ve been treating your horse with something, or if someone else has been treating your horse with something, tell your veterinarian before you start treating your horse with something else. You don’t want there to be some sort of an unforeseen reaction or complication from some sort of a medication or substance interaction that you kept secret.

WHILE YOUR HORSE IS BEING TREATED

Keep records. Keep records of the treatments, your observations, your horse’s temperature: that sort of thing. Keep records of conversations and text messages, too. Take pictures. Your records of how things are going will help in aftercare – if there’s some sort of a problem afterwards, these will serve you much better than your memory will if you need some help (from a lawyer, the state veterinary board, etc.).

Keep records. Keep records of the treatments, your observations, your horse’s temperature: that sort of thing. Keep records of conversations and text messages, too. Take pictures. Your records of how things are going will help in aftercare – if there’s some sort of a problem afterwards, these will serve you much better than your memory will if you need some help (from a lawyer, the state veterinary board, etc.).- Communicate regularly with your veterinarian as to how things are going. We really do want to know how things are going – it can be surprisingly difficult to get reports on how things are going – and it helps us nip problems in the bud. Plus, if you don’t talk to your veterinarian, it will be hard to hold him or responsible for a problem that they never knew happened.

AFTER TREATMENT

AFTER TREATMENT

- Not all treatments will be successful. The mere fact that a treatment wasn’t successful or that there was some complication does not also mean that there was malpractice. Keep the lines of communication open.

- Get a copy of your records. The original records are the property of your veterinarian. However, your veterinarian should be able to quickly and easily provide you with a copy at your request. In fact, it’s generally the law.

- If your horse dies, consider getting a necropsy. This will help you understand what happened. In addition, if you want to pursue a lawsuit, you’ll need all the evidence that you can accumulate.

LINGUISTIC NOTE: When they examine human bodies after the humans have died, the procedure is called an, “Autopsy.” The word comes from Greek. Autopsia “a seeing with one’s own eyes,” from autos- “self” + opsis “a sight.” The word has been around since the 16th century. Since horses aren’t “self,” in the sense that they aren’t humans, it’s generally preferred to use the tern, “necropsy,” where “necro-” refers to death (as in, “seeing after death.” Or, you could just call it a “post-mortem” (after death) exam and be done with it.

IF YOU THINK THERE WAS MALPRACTICE

Ask, or have your lawyer ask, for the name of your veterinarian’s insurance company. It’s unlikely that you’ll be able to settle a claim yourself.

Ask, or have your lawyer ask, for the name of your veterinarian’s insurance company. It’s unlikely that you’ll be able to settle a claim yourself.- You may be satisfied with a fee adjustment and you can certainly discuss that with your veterinarian. However, a fee adjustment is not an admission of guilt, so don’t consider it as such. On the other hand, even if things go wrong, you veterinarian is generally entitled to the fees for the services rendered. There are no guarantees in medicine and not everything bad that happens is necessarily the veterinarian’s fault.

GENERAL GUIDELINES

GENERAL GUIDELINES

- Anything that’s dispensed to you for your horse should be labeled. If it’s not labeled, get it labeled. You should know what’s being given to your horse.

- Keep medications safely stored and away from untrained hands.

- There are laws pertaining to the practice of veterinary medicine. Read and understand them before you start asserting that a veterinarian violated them. For example, a rectal tear (during a rectal exam) is not necessarily malpractice – failure to recognize that it occurred, and to refer for prompt treatment is.

- Communicate, communicate, communicate. Make sure you understand what’s being proposed and that you get all of your questions before you allow anything to be done to your horse.

Malpractice actions are difficult, agonizing, expensive, and emotionally traumatic. There’s no way to prevent or predict every complication or unforeseen circumstance. Your veterinarian has responsibilities, but when you think about it, so do you – and your horse is relying on you, too. The more prepared you are the better, no matter how things go after your horse gets treated.

Malpractice actions are difficult, agonizing, expensive, and emotionally traumatic. There’s no way to prevent or predict every complication or unforeseen circumstance. Your veterinarian has responsibilities, but when you think about it, so do you – and your horse is relying on you, too. The more prepared you are the better, no matter how things go after your horse gets treated.