In my view, sometimes it’s OK to not know exactly what a horse’s problem is. In addition, sometimes it’s OK to try a treatment without knowing the mechanism of action. Honestly, it happens more often than we’d like to admit.

In my view, sometimes it’s OK to not know exactly what a horse’s problem is. In addition, sometimes it’s OK to try a treatment without knowing the mechanism of action. Honestly, it happens more often than we’d like to admit.

However, in my view, when that happens, you shouldn’t lie about it or make stuff up.

A few years back, I treated a horse. He got better. He hasn’t had a problem since. Happily, this is not the first time this has happened, of course, or I probably wouldn’t have been doing this for 3+ decades. But I wanted to tell you about this horse in light of all of the back-and-forth that goes on when it comes to talking about treatments, and how, if, or why they might work.

The horse I treated was a three-year-old Quarter horse gelding, used for barrel racing. His owner was (and is) a long-time client with lots of experience around horses: caring, showing, riding, loving… you know. The horse had been in training for a few months, and she told me that he didn’t feel “right” behind. She said that he felt like he was “stepping under himself.” She wanted to to take a look and see if something was wrong. Having worked for my client for a couple of decades, and knowing her to be a good horseperson and a very caring owner, I was pretty sure that she was feeling something. It’s great to have relationships like that with your clients. When they have confidence in you and you have confidence in them, a lot of good things can happen for everyone involved.

The horse I treated was a three-year-old Quarter horse gelding, used for barrel racing. His owner was (and is) a long-time client with lots of experience around horses: caring, showing, riding, loving… you know. The horse had been in training for a few months, and she told me that he didn’t feel “right” behind. She said that he felt like he was “stepping under himself.” She wanted to to take a look and see if something was wrong. Having worked for my client for a couple of decades, and knowing her to be a good horseperson and a very caring owner, I was pretty sure that she was feeling something. It’s great to have relationships like that with your clients. When they have confidence in you and you have confidence in them, a lot of good things can happen for everyone involved.

I examined the horse. I watched him trot. I watched him in hand, under saddle, and on the lunge line. I did flexion tests. I used hoof testers. And…. I didn’t see anything wrong. However, when I felt the muscles on one of the hindquarters (I don’t remember which one), I was pretty sure that I identified an area of soreness. I kept going side-to-side, seeing if the response that I was getting on one side was the same as on the other side. It wasn’t – there was a difference.

I examined the horse. I watched him trot. I watched him in hand, under saddle, and on the lunge line. I did flexion tests. I used hoof testers. And…. I didn’t see anything wrong. However, when I felt the muscles on one of the hindquarters (I don’t remember which one), I was pretty sure that I identified an area of soreness. I kept going side-to-side, seeing if the response that I was getting on one side was the same as on the other side. It wasn’t – there was a difference.

The first time I ever saw a horse that reacted like this was in my 20’s. At that time, I was working with one of the founders of the American Association of Equine Practitioners, interning as a senior veterinary student. He pushed on a horse’s muscles in that same area and told me that the horse has a problem with in his whirlbone.

The whirlbone thing was news to me. Go through any text on equine anatomy and you won’t find a whirlbone (for those who love anatomy, and as I found out, it’s an old term that was used to describe the greater trochanter of the femur). However, in spite of the fact that the problem was apparently in an as yet unidentified bone, I could see what he was seeing and I could feel what he was feeling. So at least there was that.

Whirlbones

Next, was the treatment. He injected the muscle in the horse’s hindquarters in a pattern – a series of lines, really – with a few milliliters of a product made up primarily of iodine and peanut oil at a number of spots along the lines. At least, that’s what I recall was in the stuff. It was black as tar, and thick, because of the oil. The horse went home. I have no idea what happened to the horse after that.

Having just seen a horse get a diagnosis that I’d never heard of and receive a treatment for that condition that I’d also never heard of – and frankly, kind of shuddered at – made me think of several possibilities.

- This guy is nuts, or

- They sure don’t teach some important things in veterinary school (they don’t, but that’s another story, and, honestly, it’s hard to be too hard on vet school because there’s so much to teach and so little time in which to teach it), or

- I’d missed too many lectures while trying to work on my putting.

Regardless, when confronted with the three-year-old in the present day, I remembered back to my internship days. In my nearly 40 years of practice, I’d also seen a couple of other horses that had similar presentations to that horse I’d seen during my internship, I’d treated them with the oil and iodine, and they improved. So, I figured, having failed to come up with a better diagnosis, “Here’s another one.” I treated it just like the other ones, too. He got better. He hasn’t had a problem since (he’s six now).

Regardless, when confronted with the three-year-old in the present day, I remembered back to my internship days. In my nearly 40 years of practice, I’d also seen a couple of other horses that had similar presentations to that horse I’d seen during my internship, I’d treated them with the oil and iodine, and they improved. So, I figured, having failed to come up with a better diagnosis, “Here’s another one.” I treated it just like the other ones, too. He got better. He hasn’t had a problem since (he’s six now).

Only…

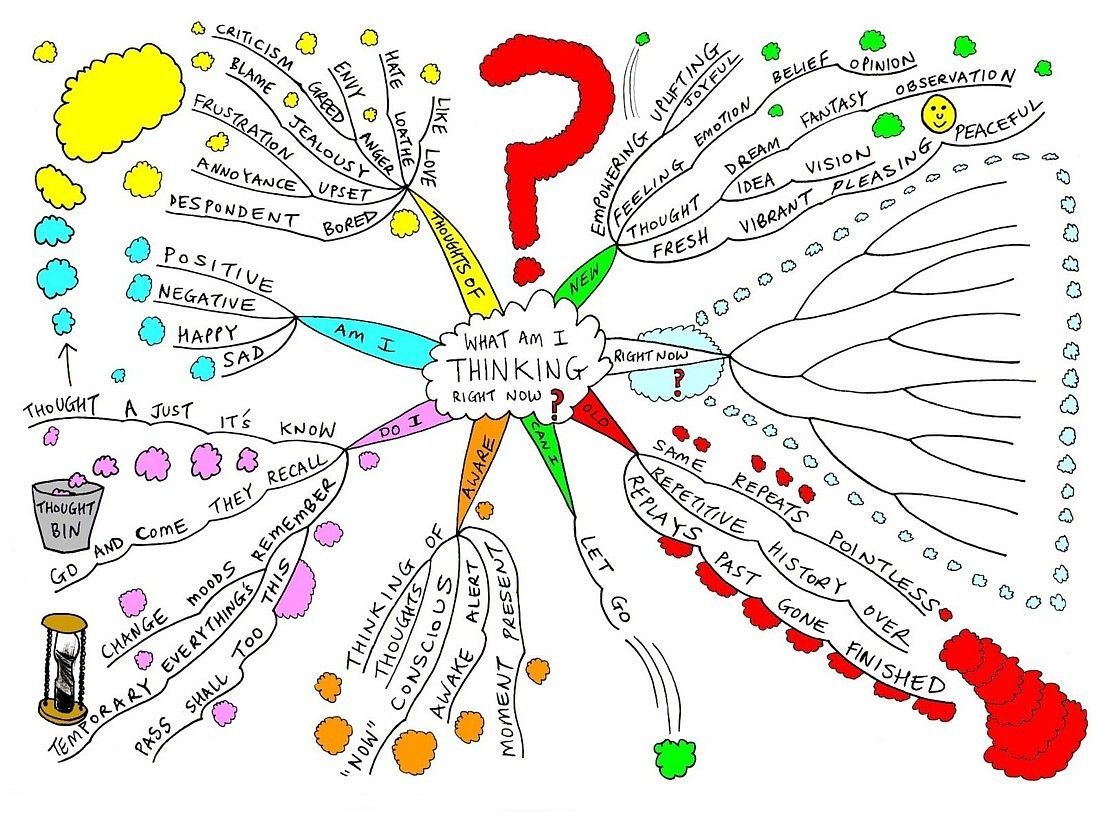

I don’t know what I really treated. And I don’t know why the treatment worked – or even if it did.

James Herriot

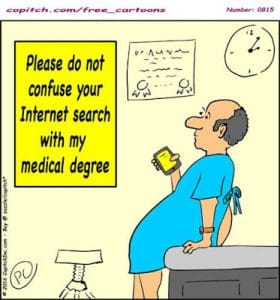

Many people get uncomfortable when a doctor says that he or she doesn’t really know what the problem is. In the wonderful old “All Creatures Great and Small” series of books, Siegfried, the veterinarian who employed James Herriot (nee James Alfred Wight), advised, (paraphrasing), “No matter what the condition is, give it a name. I don’t care if you call it McCluskey’s Disease. It has to have a name.” Apparently acolytes of such an approach, many people will identify what they’ve found with a name. Call it a subluxation. A “tight band.” A “reactive point.” Call it something. And make sure you have some sort of certification representing your expertise in coming up with such a name.

I don’t do that. When confronted with this horse, here’s what I told my client. I said (paraphrasing), “You know, I’m not sure what’s wrong with your horse. I don’t really see anything. However, I certainly respect what you’re feeling. I did find this area on your horse’s hindquarters where he reacts differently than the other side. I’ve seen a few other horses like that, too. I’m not sure what the problem is, but I have seen something like this before.”

Having been a client for nearly 30 years at that point, she was OK with that “diagnosis.”

Having been a client for nearly 30 years at that point, she was OK with that “diagnosis.”

“What should we do?” she asked.

I could have said, “Well, we’re going to use an internal blister on your horse. This will bring circulation into the area and help heal up the injured tissue. He’ll be right in no time.” I didn’t say that, however, because the idea of “blistering” is pretty archaic and has been shown to be not related to any medical fact. It was used for a couple of hundred years – still is in some circles.

I could have said, “Well, with soreness in this area, we’ve found a reactive acupuncture point. We’re going to inject into and around the acupuncture point, based on historical Chinese medical theory, in order to balance the chi/stimulate the acupuncture point in order to treat the leg.” I didn’t say that, however, because modern acupuncture is not based on historical Chinese medical theory, acupuncture points have not been shown to exist as discrete entities, talk of things like “balance” and “chi” don’t reflect anything that’s measurable or demonstrable, and also because there’s no good, consistent evidence that acupuncture has any relevant clinical effect on any condition of the horse.

I could have said, “We’ll be injecting trigger points today in order to relax the muscle spasm that’s causing the problem that you’re feeling.” However, while people who look into such things say that a trigger point is an area of tightly contracted muscle, or some sort of small muscle spasm, unfortunately, that’s all still theory, even after a few decades, and such science as there is is controversial: even a little nutty sometimes.

I could have said, “We’ll be injecting trigger points today in order to relax the muscle spasm that’s causing the problem that you’re feeling.” However, while people who look into such things say that a trigger point is an area of tightly contracted muscle, or some sort of small muscle spasm, unfortunately, that’s all still theory, even after a few decades, and such science as there is is controversial: even a little nutty sometimes.

What I did say was, “I’ve seen a couple of horses like this. I’ve injected them with this horrible sounding combination of peanut oil and iodine. I have no idea why it does anything – my best guess would be that it makes them a little sore, alters the way that they move the leg, and they get over the problem as they exercise. But I don’t know.”

If I wanted to be honest – and I did – that was the best that I could come up with.

If I wanted to be honest – and I did – that was the best that I could come up with.

My client asked for a day to think about it, but, after a day, she said, “Sure, let’s give it a try.” We did. I injected the horse, we kept him working, he got better, and he hasn’t had a problem since. If I ever see another one like that, I’ll probably do the same thing, assuming that I can get the medication.

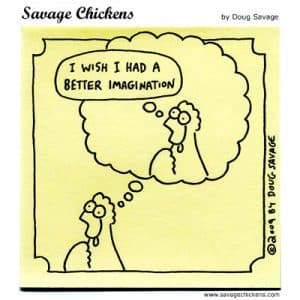

www.savagechickens.com

I’m OK with uncertainty. What I’m not OK with is making stuff up in order to make a diagnosis or a therapy sound more convincing. I’m not OK with lying to people about what the history of Chinese veterinary medicine was about. I don’t mind if people want to stick needles in their horses in hopes of finding some therapeutic effect, but I’m totally against telling them that this is based on some ancient “wisdom” or, worse, that it provides and effective and drug-free alternative to giving a horse horrible and nasty chemicals (or something like that). I don’t mind of people want to try to do something to horses with their hands, but I’m not OK with people telling horse owners that they are “equine chiropractors” when there’s no such degree, or that they are any kind of chiropractor when they haven’t gone to chiropractic school. I’m not OK with making up mechanisms of action that aren’t based in reality: circulation increases, bones out of place, mysterious energy channels, magnetic nonsense, and many, many more examples.

Anyway, a few years back, I treated a horse with a problem, with a medication. I didn’t know exactly what the problem was, and I didn’t know exactly what the medication did. I was honest about those things, I told that to my client, and we agreed to try something based on some experiences I had. Happily, the horse got better (even though one could plausibly argue that I don’t know that the “better” was because of the treatment). I was honest about my uncertainty and it worked out. In this day of curious names and dubious rationales, do you think my approach will ever catch on?