In light of all of the “options” that you have for treating your horse, thought it might be fun and, hopefully, thought provoking, to bring up a term that’s thrown around in medicine, especially by statisticians, but rarely, so it seems, in day to day practice. Statisticians, in case you don’t know one, happen to have one of the most impenetrable jobs around, but also one that’s very, very important, at least when it comes to analyzing the results of scientific tests. And the term is one that should be very important to you if you’re considering trying – or spending money on – just about anything for your horse.

The term is, “Clinical Relevance,” sometimes also known as, “Clinical Importance.” When people are doing investigations looking into whether this or that therapy, treatment, or product, is effective, one of the first questions that gets asked (or should get asked) is, “Did the thing that you were studying make a difference?” Researchers set up test conditions, test one thing or another, and then analyze the data to see if there is a difference in the outcomes. All of that data analysis is done by statisticians, using one of any number of virtually incomprehensible mathematical methods. At the end of the day, based on the results of the analysis, veterinarians like me, who have to put this stuff into practice – and who, by the way, usually aren’t very good at doing or understanding those very same incomprehensible math methods – usually get told that there was or wasn’t a “statistically significant” difference as a result of the study. And that’s one way that some people make up their minds on whether or not to try a therapy. If there’s a statistical difference, it suggests that some therapy may be worth a try.

Usually, when there is a statistical difference, this is cause for some sort of celebration back at the lab. I mean, honestly, it’s not like veterinarians aren’t aware that in the battle for equine health, we are often poorly armed, so we’re always hoping that there’s going to be some new weapon come along to help beat arthritis, colic, or whatever. When statistics indicate that there’s a statistical difference, we’re usually pretty happy to try to put that thing into practice. (I can’t say what kind of celebrations most statisticians engage in – mostly, they just move on to the next study, I think.) Of course, many therapies that are advertised to horse owners aren’t supported by any good studies – or good statistics – at all, but that’s a whole ‘nother kettle of fish.

The problem, with using a statistical difference as some sort of measuring stick of effectiveness is that the wonderful new therapy may pass some statistical hurdle, but it often doesn’t make that big a difference to the horse (or you). Sadly, it’s rare that there’s some wonderful new discovery that’s going to change equine medicine altogether. There have been a couple of such changes through history, but only a couple. Penicillin – the first antibiotic – was one of those things. Anesthetic gases that horses could inhale revolutionized equine surgery. But more often than not, what you get, when it comes to medical discoveries, is something that might or might not make that big of a difference, even if there is some measurable statistical difference in the results of some study.

This is where clinical relevance comes in, and this is what I want you to remember. When it comes to deciding whether or not to use a treatment – especially if it’s an expensive one – the question that you should be asking is how much of a difference a treatment will really make. It’s not just important to know that there’s some difference – you want to know how big of a difference there is. That is, even if you use a particular treatment, the horse may not get that much benefit from it. I mean, for one thing, your horse probably wasn’t in the study.

Honestly, it is always something of a leap of faith when it comes out to trying something on your horse. That’s why, before you decide to go all in on some treatment, you want to make sure that the effects of the treatment are big enough to change your normal way of doing things and to justify paying for the additional treatment.

Here are a couple of examples of what I’m talking about. Let’s say that someone says that your horse should be treated with a laser (they seem to be everywhere, and you can CLICK HERE to read an article I wrote about them a few years back). Without getting into all of the different kinds of lasers, and treatment regimens, and conditions that can be treated, when it comes to clinical relevance, the big questions are, “Am I going to end up anywhere different that where I would have ended up if I just let things take care of themselves,” and, “How much is this going to cost?”

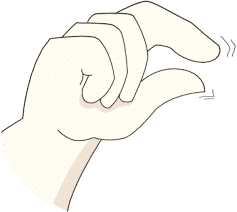

Let’s say that your horse has some sort of a cut. In fact, let’s say your horse has a really BIG cut. Let’s say he’s got this cut (in the illustration – I took care of this horse some years back). It looks terrible – that’s easy to see. You’re going to be worried, if for no other reason that you haven’t seen many big cuts like this). And you’re going to get lots of opinions – you may have lots of opinions – on what to do. Antibiotics. Laser. Hospitalize the horse. Amnion dressing. Bandage. Scarlet Oil. Violet spray. Silver spray. Nitrofurazone spray (it’s yellow). Some other color spray.

Let’s say that your horse has some sort of a cut. In fact, let’s say your horse has a really BIG cut. Let’s say he’s got this cut (in the illustration – I took care of this horse some years back). It looks terrible – that’s easy to see. You’re going to be worried, if for no other reason that you haven’t seen many big cuts like this). And you’re going to get lots of opinions – you may have lots of opinions – on what to do. Antibiotics. Laser. Hospitalize the horse. Amnion dressing. Bandage. Scarlet Oil. Violet spray. Silver spray. Nitrofurazone spray (it’s yellow). Some other color spray.

You get the point. What would you do?

Here’s what was done. The wound was washed out with a garden hose from time to time. Healed up in about 10 weeks, as I recall. Left a linear scar that didn’t bother the horse a bit. He’s fine. He jumps fences willingly and regularly. It’s kind of hard to imagine what all of that other stuff might have added, other than expense.

Here’s another way to think about it. Let’s say that a therapy is “guaranteed” to heal a wound 10% faster. That’s a lot (even if it could be shown to be true). But in the case of the wound above, that would shorten the healing time by a week. Wonderful, for sure, but at what cost? The wound ended up healing just fun with only the occasional hosing. Happy horse – great outcome – less expensive. What’s not to like?

Once you start thinking in terms of clinical relevance, all sorts of lights go on. Take the hottest trend in “sports medicine” right now, the so-called “regenerative” therapies. This slyly named group of therapies – the name certainly implies that the therapies can return tissues back to some semblance of normal – holds all sorts of “promise” for the treatment of all sorts of injuries. However, there’s currently a serious lack of evidence that they actually do anything important at all beyond the time that it takes for injuries to heal anyway. So, if you’re considering using such therapies – and the appeal is undeniable, dating at least back to Juan Ponce de Leon, in the early 1500’s – it would probably be wise to ask if they are clinically relevant, that is, if they are going to make any difference on where your horse ends up in the long run (at this point, there’s little evidence that they do).

Of course, there are other considerations when it comes to deciding if you want to use a therapy. For example, you might find some treatment that has passed statistical testing, but every time you try it the horse tries to kick you: might be wonderful, just not practical. You might think that a treatment or test could help, but it might be way too expensive to consider. Maybe the therapy has be given 6 times a day: impossible. It’s always something.

Just keep in mind that when it comes to your horse, there’s a lot of stuff that you can do. What’s important, however, is doing the stuff that really makes a difference. Just because you can do something doesn’t necessarily mean that you should. Ask if the something that you’re considering is clinically relevant. You might be surprised at the reaction.