The chemical processes that maintain life in horses (and all other species, including man), can be summed up in one word: metabolism. In the last decade or so, researchers have started describing a syndrome that affects these processes in horses. It’s called “insulin resistance” or, alternatively, “metabolic syndrome.” Scientific researchers are beginning to reveal some of the reasons that horses develop metabolic problems, and, best of all, they’re able to give some advice on what to do about them. Lucky for horse owners, taking care of these horse doesn’t require all that much in the way of time and effort (even though many people put a lot of effort into it, and with very good intentions). My own experience has been that a diagnosis of metabolic syndrome or insulin resistance tends to make people a little nuts, so here’s hoping we can bring some sense to the discussion.

The key player in IR/MS (the abbreviation helps make it easier to type) is a hormone that pretty much everybody has heard of: insulin. Its most important function is pretty straight-forward – it regulates the amount of sugar (glucose) in the horse’s blood.* A lack of insulin causes diabetes (which is almost unheard of in the horse), but a lack of insulin is not the problem with IR/MS.

With IR/MS, the problem is really quite simple: insulin doesn’t do its job. It doesn’t do its job probably because it can’t do its job. That’s because the cells in the body of the horse with IR/MS don’t respond normally to insulin. Nobody currently knows why this happens, and, to make this more complicated, it might not even be the same reason in all horses. But the result is the same in affected horses, that is, insulin becomes less effective at lowering blood sugar. And this can have some bad consequences for the horse.

When insulin isn’t working normally, IR/MS horses try to produce more insulin to try to compensate for the lack of effect (sort of the “more is better” theory of metabolism, I suppose). Of course, this doesn’t work, It’s not a bad idea, horse’s-body-wise, but, again, the problem isn’t the insulin, it’s that the cells don’t respond normally to insulin, no matter how much insulin is there. However, all of this extra insulin causes what is essentially an insulin toxicity. And too much insulin is NOT a good thing.

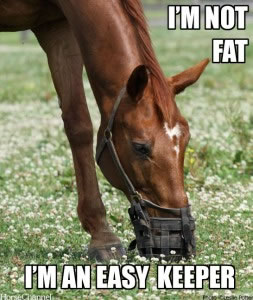

Insulin in excess of what’s needed promotes growth. Horses with IR/MS do grow – but they grow fat. Such horses are often referred to as “easy keepers,” you know, the ones that seem to blow up like a balloon on a couple of small flakes of hay. But these insulin resistant horses don’t just get fat like normal fat horses – their fat gets laid down in some pretty unusual (but typical for them) places, such as over the crest of the neck, or over the tail. Interestingly (to me, anyway) human diabetic patients who have to inject themselves with insulin on a regular basis develop localized fat deposits in the areas of injection.

Of course, insulin resistance is one of those things that happens in life, and life is not necessarily simple. So, to make things more complicated, not all horses with insulin resistance are fat, and not all fat horses have insulin resistance. However, all horses with insulin resistance – the normal looking ones and the fat ones, too – are prone to developing laminitis (CLICK HERE to read about laminitis). When it comes to IR/MS, the bottom line is that some horses are more sensitive to the effects of insulin than are others.

Of course, insulin resistance is one of those things that happens in life, and life is not necessarily simple. So, to make things more complicated, not all horses with insulin resistance are fat, and not all fat horses have insulin resistance. However, all horses with insulin resistance – the normal looking ones and the fat ones, too – are prone to developing laminitis (CLICK HERE to read about laminitis). When it comes to IR/MS, the bottom line is that some horses are more sensitive to the effects of insulin than are others.

So how do you find out if your horse has insulin resistance? People used to think that you could just measure blood sugar (glucose) and insulin levels, do a ratio, and go from there. But it turns out that this isn’t a very sensitive test, and I wouldn’t recommend it. So even though no single test has been shown to be the “gold standard,” It’s probably much better to do an oral sugar test – you basically give the horse a dose of sugar and then measure insulin levels. Horses with IR have insulin levels that go much higher than levels in normal horses. The sugar test is much more sensitive than just testing baseline levels. You can find out how to do the test, as well as about lots of minute detail about the condition in the American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine Consensus statement on Equine Metabolic syndrome, from 2010 (it’s still current). You can see if you CLICK HERE.

ONE OTHER THING: Many times, IR is noted at an age when horses are also likely to get Cushing’s syndrome (CLICK HERE to read about that). A lot of people seem to get the two things confused, but they aren’t related to each other at all. Still, if a horse has Cushing’s syndrome, it usually makes IR worse. So if you think your horse might have IR, and you like running blood tests on your horse, it’s probably a good idea to also get him tested for Cushing’s, too, particularly if he’s older.

Recognizing that a horse with IR properly is important, because the horse with IR is a horse that is at risk for developing laminitis. There are many things that people do to treat horses with IR, but the most important things are two things that bedevil just about everyone: diet and exercise.

WHAT YOU SHOULD DO

1. Proper Diet. The dietary goals in treating a horse with IR are to get him leaner, and to make sure that he’s eating the right things. It’s not just a matter of starving the horse, and running it around more; what the horse eats is nearly as important as how much he eats. You can read about diets for IR/MS if you CLICK HERE.

1. Proper Diet. The dietary goals in treating a horse with IR are to get him leaner, and to make sure that he’s eating the right things. It’s not just a matter of starving the horse, and running it around more; what the horse eats is nearly as important as how much he eats. You can read about diets for IR/MS if you CLICK HERE.

The best feeds for IR/MS horses are those that have a low glycemic index. The glycemic index of a food is just a number, but for the horse with IR, that number means something. The glycemic index number represents the ability of a food to increase the level of glucose in the blood (as compared to glucose itself). For horses with IR, it’s best to feed them things that have a low glycemic index.

Things that tend to be not good for IR horses are things like pasture grazing, sweet feed, or low fiber feeds. Even with those guidelines, it’s kind of hard to tell if a feed as a low glycemic index just by looking at it. So, if your into being all analytical, you can have your horse’s feed analyzed for sugar:starch content, at places like Dairy One, in New York. If you don’t want to have the feed analyzed, but you want to make sure you’re feeding a low starch diet, a number of companies make complete, low starch, pelleted rations. There are lots of good choices.

PRAGMATIC NOTE ONE: If you’re concerned that your horse as MS/IR, and you don’t want to pay a lot of money for testing, you can usually just change his diet and go from there. A good diet and exercise are good for any horse.

PRAGMATIC NOTE TWO: Your IR/MS horse is not going to die if he gets a mouthful of grass, a carrot once in a while, or a peppermint. You can go on a diet, and still have a cookie from time to time. Still, if your horse has MS/IR, you should limit his access to pasture, and he certainly shouldn’t get the majority of his calories from fresh grass.

2. Regular Exercise. The benefits of regular exercise are too numerous to list. So I won’t. Just get your horse out. It will be good for both of you.

THINGS YOU CAN DO (but probably don’t need to do)

If you’re like most people, you probably want to do everything that you can to help your horse with MS/IR. And, predictably, you’ll find lots of suggestions on things that you can/should/must do. But just because you can do something doesn’t mean that you should do it, and for goodness sake, don’t make yourself crazy. Still, here are some comments on a couple of things that people will probably bring up:

1. Thyroid hormone. Thyroid hormone helps horses with insulin sensitivity short term. In fact, most fat horses with insulin sensitivity used to get diagnosed as “hypothyroid” when they really weren’t. The thing is, thyroid hormone does help burn calories, and it may even temporarily help insulin do its job. Of course, dietary management and exercise are the most important things, but if you’re having trouble getting weight off your IR horse, giving him some thyroid hormone can help. But remember, IR horses are NOT hypothyroid, and they don’t need lifelong supplementation (in fact, I’ve made something of a career taking horses OFF their thyroid medication).

2. Metformin – Metformin is a drug that is used to lower blood glucose in humans. It has a bit of a spotty record in horses, probably because horses don’t seem to absorb it very well (if they don’t absorb it, it can’t work, of course).

2. Supplements. If you don’t want to read anymore, then just remember this: no supplements have been shown to do IR/MS horses any good. That fact, of course, hasn’t deterred any number of supplement makers from coming up with countless “metabolic supplements” to give your horse a hand (and also to put a hand in your wallet or purse). IR/MS supplements usually have things like chromium, magnesium, and even cinnamon in them (by the way, I fully support the use of cinnamon, especially in some desserts, but also in Lebanese Cinnamon Chicken, as well as in cinnamon toast, where it’s mixed with sugar, then toasted on bread with butter. I just don’t support its use in horses with IR). If you have some extra money that you want to throw away, IR/MS supplements are certainly one place you can do it.

2. Supplements. If you don’t want to read anymore, then just remember this: no supplements have been shown to do IR/MS horses any good. That fact, of course, hasn’t deterred any number of supplement makers from coming up with countless “metabolic supplements” to give your horse a hand (and also to put a hand in your wallet or purse). IR/MS supplements usually have things like chromium, magnesium, and even cinnamon in them (by the way, I fully support the use of cinnamon, especially in some desserts, but also in Lebanese Cinnamon Chicken, as well as in cinnamon toast, where it’s mixed with sugar, then toasted on bread with butter. I just don’t support its use in horses with IR). If you have some extra money that you want to throw away, IR/MS supplements are certainly one place you can do it.

Insulin resistance is an active area of research and study, not only in horses, but also in people. There’s a lot that’s yet to be discovered about the condition. For example, in all likelihood, genetic markers for IR will ultimately show up, but even those aren’t likely to provide a simple solution. Still, hopefully genetic testing will ultimately help us understand things like what makes ponies be prone to IR/MS, as opposed to Thoroughbreds, who seem to be relatively resistant to the condition.

Insulin resistance is an active area of research and study, not only in horses, but also in people. There’s a lot that’s yet to be discovered about the condition. For example, in all likelihood, genetic markers for IR will ultimately show up, but even those aren’t likely to provide a simple solution. Still, hopefully genetic testing will ultimately help us understand things like what makes ponies be prone to IR/MS, as opposed to Thoroughbreds, who seem to be relatively resistant to the condition.

Even though IR/MS is a bit of a nuisance, horses with IR can live long, healthy, and productive lives with just a little attention to proper diet and exercise. Sound like anyone you know?

******************************************************************************

*Insulin also helps regulate other nutrients, but it’s the regulation of blood sugar that’s the most well-known function.