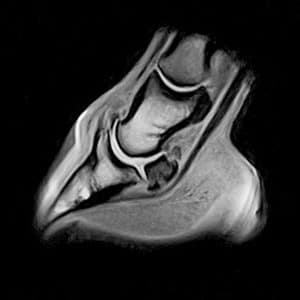

One of the fun things about my career has been watching the introduction of new diagnostic tests to help try to figure out what’s wrong with a particular horse. From MRI to CT, from bone scans to digital radiography, and from genetic tests on hair to testing a horse’s blood for a newly discovered disease, we move forward, step by step, learning more about the problems that beset the horse.

One of the fun things about my career has been watching the introduction of new diagnostic tests to help try to figure out what’s wrong with a particular horse. From MRI to CT, from bone scans to digital radiography, and from genetic tests on hair to testing a horse’s blood for a newly discovered disease, we move forward, step by step, learning more about the problems that beset the horse.

And yet…

We certainly don’t know everything. In fact, sometimes we don’t need to know everything. Sometimes trying to learn more and more just leads to added costs, without any benefit to you or the horse. Here’s something that happened to me fairly recently.

I was called out to look at a horse that was limping on his right front leg. He was 12 or so, hadn’t had any problems that anyone had recognized, but all of a sudden, he started limping. The lameness couldn’t be pinned on a particular incident (which happens a lot) but, understandably, the owner wanted to know what was going on, and especially wanted to know that everything was going to be OK.

I could see that the horse was off, so the first thing that I did was feel his legs. There are a couple of big arteries at the back of the pastern, and, when the horse’s foot is sore and/or inflamed the character of the pulse in the arteries will change: become stronger. It’s like when you hit your thumb with a hammer (an experience of which I am not proud); your thumb throbs. I picked up the leg and pinched his foot with a hoof testers, asking, in effect, “Does that hurt? Does that hurt?” And while the horse didn’t talk, he certainly did clearly let me know when I found the sore spot and tried to pull his foot out from between my legs.

I could see that the horse was off, so the first thing that I did was feel his legs. There are a couple of big arteries at the back of the pastern, and, when the horse’s foot is sore and/or inflamed the character of the pulse in the arteries will change: become stronger. It’s like when you hit your thumb with a hammer (an experience of which I am not proud); your thumb throbs. I picked up the leg and pinched his foot with a hoof testers, asking, in effect, “Does that hurt? Does that hurt?” And while the horse didn’t talk, he certainly did clearly let me know when I found the sore spot and tried to pull his foot out from between my legs.

“What do you think?” asked my client.

“Well,” I said, “It looks like he’s got a sore spot on his foot. I don’t think it’s the shoe (the horse hadn’t been shod recently) but I think his foot is a little tender. He’s really not very bad, and he’ll probably be OK in 3 – 4 weeks.”

That could have been that. But it wasn’t.

The owner wanted to know more. “Are you sure it’s the foot?”

We do have our ways of trying to pinpoint lameness in the horse, although, to be strictly honest, “pinpoint” is a bit of an exaggeration. It’s more like we can often get a pretty good idea of the general area from which the horse’s lameness originates. In the case of the foot, it’s usually not that hard to tell if it’s the source of the lameness. In fact, something like 70% of all cases of equine lameness have their origin in the horse’s foot.

NOTE: If someone asks your opinion as to why his or her horse is lame, unless you see something obvious, like a big lump, or a sore swelling, always guess that it’s the foot. You’ll be right about 70% of the time, which, honestly, isn’t too bad, and will make you look like something of a savant a good bit of the time.

NOTE: If someone asks your opinion as to why his or her horse is lame, unless you see something obvious, like a big lump, or a sore swelling, always guess that it’s the foot. You’ll be right about 70% of the time, which, honestly, isn’t too bad, and will make you look like something of a savant a good bit of the time.

Anyway, I said, “Sure, we could block the foot.” That’s a procedure where we place a bit of anesthetic over the nerves running down to the foot. If the sore spot goes numb, the horse trots sound, and we can infer that the lameness is coming from that area.

“Let’s do that,” the owner said.

So, I placed a bit of anesthetic over the nerves (there are two – one on each side of the back of the pastern), and, in a few minutes, the horse was trotting sound.

“Well, there you go,” I said. “We now know with a great deal of confidence that it’s the foot.”

“Well, there you go,” I said. “We now know with a great deal of confidence that it’s the foot.”

“What do you think we should do?” the owner asked.

“Honestly, I don’t think he’s very bad, and in 3-4 weeks I think he’ll be fine,” I repeated.

Then came the next question: “But could it be something worse? Could the bone be a problem?”

“Well, it could be, I guess, but the chances of that are really small. He’d probably be a lot worse if it were a bone problem,” I said.

Then came the next question. “What about X-rays?”

I mean, it wasn’t an unreasonable question. X-rays can help us identify some problems, and especially when those problems are in the bone. But like I said, I didn’t think that X-rays would be likely to tell us much.

I mean, it wasn’t an unreasonable question. X-rays can help us identify some problems, and especially when those problems are in the bone. But like I said, I didn’t think that X-rays would be likely to tell us much.

“I’d feel better if we took some X-rays,” the owner said. So we did. And they were normal.

“What do you think we should do?” the owner asked.

“Honestly, I don’t think he’s very bad, and in 3-4 weeks I think he’ll be fine,” I repeated (again).

“But what about the soft tissue?” the owner asked.

To be fair, this was not a stupid question. In a sense, all lameness problems of the horse are either in the hard tissue (i.e., bone) or the soft tissue (the not bone stuff – ligament, tendon, and such). X-rays tell us something about the hard tissue, but when it comes to looking at the stuff that’s not bone, they’re really not very useful.

Which is what I said.

“Honestly, the only real way to get a good look at the soft tissue in the foot is to do an MRI. But that will cost around $3,000. But I don’t think you need to do that,” I said.

To which the owner replied, “I think I’d like to make sure.”

So, a few days, and about $3,000.00 later, we had our MRI. It didn’t show that anything in the foot was abnormal.

So, a few days, and about $3,000.00 later, we had our MRI. It didn’t show that anything in the foot was abnormal.

“What do you think we should do?” the owner asked.

“Honestly, I don’t think he’s very bad, and in 3-4 weeks I think he’ll be fine,” I repeated (again).

In three or four weeks, the horse was fine. He hasn’t looked back.

And I’m left scratching my head. I mean, there was nothing really wrong in what happened, nobody was hurt; it just seemed so pointless. Had it been, say, 25 years ago, taking a whole bunch of X-rays and seeing them in a flash, at the barn, wouldn’t have been a possibility. Had it been, say 20 years ago, MRI wouldn’t have been a possibility. We would have had a good, thorough physical exam, the horse would have had a few weeks off, and then he would have been fine. That’s the outcome that we wanted, of course. We got the same outcome, just for a lot more money.

I guess the reason this story is worth telling is that I don’t think it’s necessary to always go down a diagnostic rabbit hole with your horse. Knowledge for the sake of knowledge is fine, but it comes at a cost, and you have to pay the cost. The benefit of that extra knowledge is often uncertain – the cost is not. Before you pay for any diagnostic test, make sure you have an idea of what it might tell you, and how that knowledge might affect the treatment given. Time is often going to be a necessary part of any healing and recovery that goes on for any condition of your horse, and as long as you’re willing to give him a little time, things will often turn out OK.

I guess the reason this story is worth telling is that I don’t think it’s necessary to always go down a diagnostic rabbit hole with your horse. Knowledge for the sake of knowledge is fine, but it comes at a cost, and you have to pay the cost. The benefit of that extra knowledge is often uncertain – the cost is not. Before you pay for any diagnostic test, make sure you have an idea of what it might tell you, and how that knowledge might affect the treatment given. Time is often going to be a necessary part of any healing and recovery that goes on for any condition of your horse, and as long as you’re willing to give him a little time, things will often turn out OK.

That’s not to say that all of the tests that can be done aren’t useful: far from it. It’s just that depending on your circumstances, you may not need to pay for them. You’ll have to bring your purse or wallet to the diagnostic process, but bring your common sense, too.