I thought that it might be useful to write some thoughts about lameness exams, since, 1) At some point, it seems that just about every horse is going to go lame, and 2) There seem to be seemingly limitless approaches to performing a lameness exam. Understanding the process can go a long way towards helping you make a sound decision – both medically and financially – on what to do if your horse goes lame.

I thought that it might be useful to write some thoughts about lameness exams, since, 1) At some point, it seems that just about every horse is going to go lame, and 2) There seem to be seemingly limitless approaches to performing a lameness exam. Understanding the process can go a long way towards helping you make a sound decision – both medically and financially – on what to do if your horse goes lame.

IT’S NOT NECESSARILY EASY

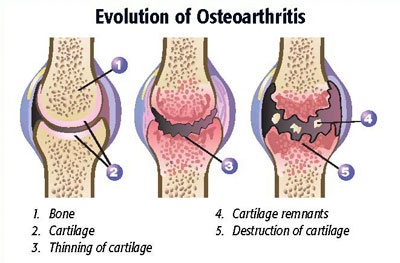

The first thing that you have to understand about a lameness exam is that it’s not always easy: at least it should always be easy. Sure, sometimes a horse gets a nail in his hoof, and won’t put his foot down. It’s an obvious problem. Such cases aren’t usually much of a diagnostic challenge (although the response to treatment depends entirely on where and how deep the nail went in), but they’re also not that common. Similarly, big swollen tendons, or bony enlargements that can be felt (and often seen) around arthritic joints tend to lead the astute observer to pretty quickly solve the question of, “Why is my horse lame?”

However, sometimes, “solutions” to lameness problems are apparently presented quickly and easily by a fairly cursory exam: a pinch, a poke, or a prod is said to indicate some problem that requires some treatment. Be careful of these sorts of approaches (more on that in a bit) – diagnosing the cause of a subtle lameness in a horse can take a good bit of time.

However, sometimes, “solutions” to lameness problems are apparently presented quickly and easily by a fairly cursory exam: a pinch, a poke, or a prod is said to indicate some problem that requires some treatment. Be careful of these sorts of approaches (more on that in a bit) – diagnosing the cause of a subtle lameness in a horse can take a good bit of time.

However, my point isn’t so much about what particular things we can (sometimes) diagnose during a lameness exam, rather, it’s to kind of take you through the general principles of a lameness exam and stop at couple of points along the way, so that you don’t get overwhelmed by the process.

ACT ONE: DO YOU NEED A LAMENESS EXAM?

The first thing that you might want to consider is whether or not you really need to get your horse examined for lameness. In a horse that hasn’t had any problems previously, or, conversely, in a horse that has known problems (say, arthritis of some joint), the fact that there might be an occasional episode of lameness really shouldn’t be all that surprising. If you’re a weekend athlete and you overdid it in a burst of irrational exuberance, or if you’re a former athlete trying to relive his or her glory days, you’ve probably had an episode of soreness and stiffness in the following day(s) that, while annoying and uncomfortable, didn’t also require a trip to the orthopedic surgeon or the emergency room. Horses are like that, too. In fact, given all of the various things that they get (have) to do with someone on their backs, it’s kind of surprising that they’re not limping around more often. But just like you, a mild owie or a short stride often isn’t the end of the world, and with a bit or rest and TLC, many things just get better.

The first thing that you might want to consider is whether or not you really need to get your horse examined for lameness. In a horse that hasn’t had any problems previously, or, conversely, in a horse that has known problems (say, arthritis of some joint), the fact that there might be an occasional episode of lameness really shouldn’t be all that surprising. If you’re a weekend athlete and you overdid it in a burst of irrational exuberance, or if you’re a former athlete trying to relive his or her glory days, you’ve probably had an episode of soreness and stiffness in the following day(s) that, while annoying and uncomfortable, didn’t also require a trip to the orthopedic surgeon or the emergency room. Horses are like that, too. In fact, given all of the various things that they get (have) to do with someone on their backs, it’s kind of surprising that they’re not limping around more often. But just like you, a mild owie or a short stride often isn’t the end of the world, and with a bit or rest and TLC, many things just get better.

NOTE: Of course, if you can’t sleep at night because you’re consumed with worry because your horse feels “uneven” all of a sudden, by all means, there’s nothing wrong with getting him examined. It’s just that a lot of horses get better on their own, and you might be able to go to a dinner or two with the money you saved.

Ditto the older horse, or the arthritic horse. You’ve probably already had an exam done and you probably already know he’s got arthritis. If your horse is in his 20’s, if he has a bit of arthritis, that shouldn’t even be much of a surprise. Regardless, there’s no cure for it. There are just lots of treatment options that might make things a little better for a while: maybe. Alternatively, it’s often possible to just nurture the arthritic horse along, reduce (but certainly not eliminate) exercise, and give him a bit of medication to help him deal with the discomfort: kind of like exactly the way arthritic people take care of themselves. You don’t have to go to the doctor every week. You should enjoy the ride and be grateful for the time you have together.

Ditto the older horse, or the arthritic horse. You’ve probably already had an exam done and you probably already know he’s got arthritis. If your horse is in his 20’s, if he has a bit of arthritis, that shouldn’t even be much of a surprise. Regardless, there’s no cure for it. There are just lots of treatment options that might make things a little better for a while: maybe. Alternatively, it’s often possible to just nurture the arthritic horse along, reduce (but certainly not eliminate) exercise, and give him a bit of medication to help him deal with the discomfort: kind of like exactly the way arthritic people take care of themselves. You don’t have to go to the doctor every week. You should enjoy the ride and be grateful for the time you have together.

ACT TWO: SO, YOU’VE DECIDED TO DO THE EXAM – NOW WHAT?

Once you’ve decided to get a lameness exam done – and, again, by all means, it never hurts to have more knowledge – you should expect to get a good, thorough physical exam of your horse before anyone ever watches him move. Horses give all sorts of clues to what’s wrong them when a leg hurts. A clue might be an area of swelling, or a joint that is sore when it gets bent, a quick reaction when a hoof gets pinched, or an unusually strong reaction when an area gets poke or prodded. A good thorough physical exam is important and it can give you clues as to what’s going on. There’s a sore spot, for sure, but it’s likely to be attached to an entire horse.

Once you’ve decided to get a lameness exam done – and, again, by all means, it never hurts to have more knowledge – you should expect to get a good, thorough physical exam of your horse before anyone ever watches him move. Horses give all sorts of clues to what’s wrong them when a leg hurts. A clue might be an area of swelling, or a joint that is sore when it gets bent, a quick reaction when a hoof gets pinched, or an unusually strong reaction when an area gets poke or prodded. A good thorough physical exam is important and it can give you clues as to what’s going on. There’s a sore spot, for sure, but it’s likely to be attached to an entire horse.

However, the mere fact that your horse gives a response to some sort of physical stimulus on a physical exam isn’t (or shouldn’t be) all the evidence you need, when it comes to a lameness diagnosis. I say this because I hear a lot about – and occasionally see – someone pinching a horse’s neck or pushing down on his back or squeezing a ligament, and then concluding that a problem area has been discovered, and needs treatment. Sometimes, that’s good enough, but often, not only isn’t it good enough, it’s not even close. Unsurprisingly, horses don’t like to be pinched, pushed, or squeezed any more than any other living creature and they can object to such stimuli: quite regularly, actually. So, if you’re presented with a bunch of treatment options after someone has simply annoyed your horse with a pinch or prod, it’s probably a good idea to ask for some more evidence of the problem before you go about treating it. Otherwise stated, don’t do it like this.

ACT THREE: HOW IS THE HORSE MOVING?

You can learn a lot from performing a good physical exam on a horse – sometimes that’s all you need to do. However, if you’re worried that your horse is, or might be, lame, and especially if the problem is subtle, you’re probably also going to watch him in motion.

Not a cause of lameness

NOTE: You don’t ONLY just want to watch him in motion. I’ve seen far too many people, watching from the edge of the arena, opine, “I think that horse is lame, maybe it’s in his shoulder/he needs his hocks injected/etc.” The key word here is “maybe” and it’s equally applicable to phrases such as, “Maybe he’d just having an off day,” or, “Maybe some space alien came down and overstimulated him with a gamma ray gun.” Maybe covers a lot of bases.

SECOND NOTE: If you want to persist in annoying your friends by opining that their horse is lame, and you’re going to venture a guess, you should guess the problem is in the front foot. The majority of ALL lameness comes from the front feet, so if you’re insistent on being a nudge, at least you should increase your chances of being right.

Anyway, sometimes lameness is pretty apparent and sometimes it’s not. When it’s apparent, it’s usually because the horse is shifting his weight around, trying to avoid putting too much pressure on the sore leg. We do that when our legs hurt. That leads to characteristic behaviors, such as the head going, “Up on the bad leg, and down on the good leg.” Or, it could be more subtle, maybe only showing up when the horse goes in a certain direction, or under saddle. Regardless, it’s probably a good idea to watch your horse move, even in a variety of circumstances, before considering doing any additional testing.

Anyway, sometimes lameness is pretty apparent and sometimes it’s not. When it’s apparent, it’s usually because the horse is shifting his weight around, trying to avoid putting too much pressure on the sore leg. We do that when our legs hurt. That leads to characteristic behaviors, such as the head going, “Up on the bad leg, and down on the good leg.” Or, it could be more subtle, maybe only showing up when the horse goes in a certain direction, or under saddle. Regardless, it’s probably a good idea to watch your horse move, even in a variety of circumstances, before considering doing any additional testing.

INTERMISSION: TIME FOR A PAUSE?

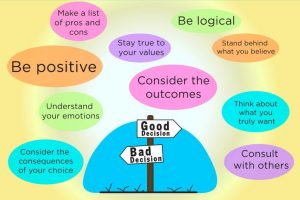

At this point, it might be worth taking a deep breath. That’s because after having done a physical exam, and after having watched the horse move, you should have some insight into a fairly important question, that is, “Is this problem a big deal or not? And, if it’s not a big deal, here’s one more thing I want you to remember about lameness exams.

It’s perfectly OK to not know immediately and exactly what is causing your horse to show signs of lameness. It’s perfectly OK to say, ‘You know, since this doesn’t looks serious, since it doesn’t look like a problem that is going to result in imminent death or dismemberment, maybe we should wait a little bit and check him again.”

It’s perfectly OK to not know immediately and exactly what is causing your horse to show signs of lameness. It’s perfectly OK to say, ‘You know, since this doesn’t looks serious, since it doesn’t look like a problem that is going to result in imminent death or dismemberment, maybe we should wait a little bit and check him again.”

Honestly, this is what happens in human orthopedics all the time. If you twist your ankle, for example, it’s not always mandatory to get X-rays taken, or to run off and jump into an MRI tube. Often, after having examined you, the doctor might just suggest that you take a bit of time off and take it easy: which is OK to do with horses, too.

Honestly, I think that there’s too much pressure put on horse owners to try to figure out EXACTLY what’s wrong. It’s certainly possible to continue a lameness exam far beyond a good physical exam and watching the horse move; it’s done all the time. It’s possible to do stress test and nerve blocks and ultrasound exams and use inertial sensors, take X-rays and bone scans and brightly colored thermographs, and look even deeper with MRIs and CT scans. That’s sort of the rest of the play, after the intermission. Or, if you like to venture into the unknown, you can run off and try other devices or approaches that have no scientific evidence behind them, but at least have alluring promises, websites, and brochures.

Honestly, I think that there’s too much pressure put on horse owners to try to figure out EXACTLY what’s wrong. It’s certainly possible to continue a lameness exam far beyond a good physical exam and watching the horse move; it’s done all the time. It’s possible to do stress test and nerve blocks and ultrasound exams and use inertial sensors, take X-rays and bone scans and brightly colored thermographs, and look even deeper with MRIs and CT scans. That’s sort of the rest of the play, after the intermission. Or, if you like to venture into the unknown, you can run off and try other devices or approaches that have no scientific evidence behind them, but at least have alluring promises, websites, and brochures.

But, frankly, much of the time, when you do additional tests, and you find out EXACTLY what’s wrong, you find out that… well… basically, you’re going to have to wait a little bit – maybe do some sort of rehab program – and then check him again. So, unless there’s something obviously bad, or unless you just can’t stand it, sometimes waiting a bit and seeing how your horse does after a lameness episode works out just fine.

A FINAL REVIEW

So, in sum, here’s what I think. If your horse is lame, or if you think your horse might be lame, by all means, get a good veterinarian out to take a look. Have him or her do a good physical exam. Watch your horse move. Maybe even ride him so you can show what  you think the problem is. But after that, start asking some questions. Before you start down the road of lots more diagnostics and lots more treatments, make sure you know how much things are going to cost. Make sure you have a good idea about what you’re going to get for the money you spend. Make sure you ask how things would be different if you DON’T do anything more.

you think the problem is. But after that, start asking some questions. Before you start down the road of lots more diagnostics and lots more treatments, make sure you know how much things are going to cost. Make sure you have a good idea about what you’re going to get for the money you spend. Make sure you ask how things would be different if you DON’T do anything more.

Yes, you want to know what’s wrong (assuming something’s wrong). But what you REALLY want to know, at least right off the bat, is if your horse’s lameness is likely to be a big deal, and you can often get an idea of that without paying for a lot of expensive other stuff. Veterinary medicine really can do a lot to help determine exactly what’s going on, and the advances in diagnostics that have happened over my career have truly been remarkable. If your horse is super valuable, and if you have the money, or if you’re really worried, you’ll undoubtedly be motivated to get more information, and understandably so. There’s nothing wrong with that. However, sometimes all of that additional information doesn’t really amount to much, at least insofar as getting your horse back to being OK goes. And at the end of the day, getting back to OK is really all that matters, right?