If you want to elicit fear in someone who owns a horse, tell that person that you think that his or her horse has “navicular.” The story of the horse’s navicular bone is a curious and instructional tale that speaks to how diagnoses and therapies come into vogue, and how hard they can be to get rid of once they are in vogue. It’s also about why you should ask a lot of questions if your horse gets diagnosed as one with “navicular disease.”

NOTE: This story is also a good illustration of why you should be careful before you jump into the latest new treatment boat. Today’s treatment that nobody uses anymore is often yesterday’s “cutting edge” therapy. The list is long, and every year – sometimes every few weeks – there’s another one for horse owners to buy.

But this story starts with the horse’s navicular bone. People have recognized that the horse’s navicular bone can give some horses all sorts of problems for centuries.* And it was, and has pretty much always been, a very bad disease, because once the horse’s navicular bone is shot, you can’t fix it. (I wrote a book on navicular disease – you can see it if you CLICK HERE. It’s needs to be updated just a little – another project – but it’s still pretty good, even if I do say so myself).

It’s a truism that when horse’s have problems, veterinarians (and many other folks) want to make horses better. So, in the 20th century, people started to really look closely at navicular bones, to try to figure out what caused the problem, and to see if it could be prevented, or treated. They dissected navicular bones, they X-rayed navicular bones, and they advanced theories about what caused navicular bones to go bad.

They kept very busy.

One of the first things that they noticed was that, when you took X-rays of the navicular bone, the bones of some horses looked like they had holes in them. Some of the horses had more holes than others. And so it was determined that holes (also given descriptive names like “lollipops” or “channels”) were bad, and that a lack of holes was good. And, importantly, it was easy.

VOICEOVER: … and, yea, verily, so it was that holes in the navicular bone became diagnostic for “problems,” (not only now, but in the future, too).

It was also determined that if you shot a bit of anesthetic over the nerves that run down the back of the horse’s pastern (the palmar digital nerves), you could make many horses that were limping go sound. Horses limp because something hurts – make the spot that hurts numb and, voilà, the horse goes sound. Branches of the nerves on the back of the pastern run right on down to the navicular bone. So, in the 1980’s, if you had a limping horse, and he stopped limping once you shot some anesthetic over his nerves, and he had some holes in his X-rays, he was probably diagnosed as being “navicular.”

VOICEOVER: … and yea, verily, so it was that a simple nerve block became “diagnostic” for navicular disease.

It was very clean and easy. But alas, it was not to last.

Somewhere towards the end of the 1970s, a British veterinarian by the name of Dr. Chris Colles came up with a theory. He asserted that disease of the navicular bone was caused by a lack of blood to the navicular bone – he said that little clots in the arteries that go to the bone caused the bone to die, and deteriorate (the process is called ischemic necrosis). Thus, in his view, the possible cure for disease of the navicular bone was to get the blood flowing. Thus armed with a plausible theory – and even a study or two – Dr. Colles (who, as far as I remember, was a great guy) got people going on treating “navicular” horses with rat poison. Not rat poison like you’d buy at the home improvement store,** but warfarin, a drug that gets in the way of the blood’s clotting process (the same drug has been used for decades used to treat humans who have had a stroke, although newer drugs are taking its place). Amazingly, many horses that became sound with an anesthetic block, and had some holes in their X-rays, got better after getting warfarin.

Somewhere towards the end of the 1970s, a British veterinarian by the name of Dr. Chris Colles came up with a theory. He asserted that disease of the navicular bone was caused by a lack of blood to the navicular bone – he said that little clots in the arteries that go to the bone caused the bone to die, and deteriorate (the process is called ischemic necrosis). Thus, in his view, the possible cure for disease of the navicular bone was to get the blood flowing. Thus armed with a plausible theory – and even a study or two – Dr. Colles (who, as far as I remember, was a great guy) got people going on treating “navicular” horses with rat poison. Not rat poison like you’d buy at the home improvement store,** but warfarin, a drug that gets in the way of the blood’s clotting process (the same drug has been used for decades used to treat humans who have had a stroke, although newer drugs are taking its place). Amazingly, many horses that became sound with an anesthetic block, and had some holes in their X-rays, got better after getting warfarin.

And all was good. I mean, how easy could it be? Block a couple of nerves, shoot a couple of X-rays, give a medicine, the horse gets better… AMAZING!

VOICEOVER: … and, yea, verily, navicular disease became a problem with blood circulation that was treated with blood thinners.

Well, sort of good. The problem with giving a poison to a horse is that, well, it poisons them. Warfarin kills rats because it makes them bleed to death internally. So horses that got warfarin had to be closely monitored to make sure that their blood still clotted, which was important, but something of a pain. And that became a bit of a problem.

THREE TRUISMS ABOUT MEDICAL TREATMENTS:

1) Treatments that are a pain are less likely to be administered than treatments that aren’t a pain.

2) Otherwise stated, when it comes to treatments, the easier it is to do something, the better.

3) Nobody likes treatments that have really nasty side effects.

So, in the early 1980’s, thinking that the blood supply was the key to navicular disease, and being acutely aware that administering warfarin was a pain in the backside, other British investigators proposed the use of isoxsuprine for the treatment of navicular disease. And they concluded that the drug was very effective, and that it made horses that they had diagnosed with navicular disease (whether they had it or not) go sound, and stay sound. Isoxsuprine was pretty cheap, and very safe, and could be given in pill format. It wasn’t a pain. And, even better, there was one small study that supported it’s use!

And all was good (again).

VOICEOVER: … and yea, verily, isoxsuprine became the treatment of choice for navicular disease.

And then things got messy.

In the mid-1980’s, a study was done where a pile of X-rays was thrown on a table (almost literally). Some of the horses had been diagnosed with navicular disease, and others were normal. Veterinarians were asked to look at the X-rays, and decide which ones belonged to the lame horses, and which ones belonged to the sound horses. And…. they couldn’t. Then additional studies came along, showing that there was tremendous variation in the appearance of navicular bones of normal horses. Normal horses had all sorts of holes, channels… whatever. Then, even more studies came along – including one I did in 1994 – that showed that you couldn’t predict if a horse would become lame based on the appearance of his navicular bone X-rays. And later studies involving CT scanning showed that navicular bone X-rays don’t provide a particularly good picture of the navicular bone anyway. All of a sudden, we, as a veterinary profession, went from being very confident in saying that a horse had – or was going to get – navicular disease, based on his X-rays, to realizing that we probably didn’t know very much after all (or, at least some of us went to that spot).

But then it got worse.

People started looking at what we were doing when we put anesthetic over the nerves that ran down the back of the pastern. Turns out, veterinarians weren’t just making the navicular bone numb, they were blocking most of the foot. And there a whole bunch of things inside the horse’s foot that can get injured. Turns out that many of those horses that had holes in the navicular bone on X-rays, that also went sound after a nerve block, did not also have navicular disease.

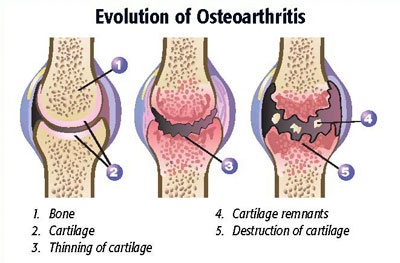

And, believe it or not, it got even worse.  Folks that were looking for the cause of navicular disease kept looking, they did dissections of navicular bones, and they found out that there was no evidence that navicular disease was caused by a lack of blood supply to the navicular bone. Diseased navicular bones didn’t look like bones that lose their blood supply. In fact, diseased navicular bone look at lot like joints that have osteoarthritis. So, the underlying rationale for prescribing things like warfarin, or isoxsuprine, turned out to be wrong all along.

Folks that were looking for the cause of navicular disease kept looking, they did dissections of navicular bones, and they found out that there was no evidence that navicular disease was caused by a lack of blood supply to the navicular bone. Diseased navicular bones didn’t look like bones that lose their blood supply. In fact, diseased navicular bone look at lot like joints that have osteoarthritis. So, the underlying rationale for prescribing things like warfarin, or isoxsuprine, turned out to be wrong all along.

And, believe it or not, it still got worse.

People then started looking at isoxsuprine. It turns out that when you give a horse isoxsuprine pills, only 2.2% of it is actually available to the horse, and most of that gets taken out of the system right away by the horse’s liver. Studies in horses showed that there weren’t any effects on the horse’s cardiovascular system following oral administration. Another study showed that it didn’t have any pain-relieving effects, either. All of which indicated – to people that were paying attention anyway – that the rationale for the use of isoxsuprine for the treatment of navicular syndrome (or laminitis, another popular condition for which isoxsuprine has been advocated) – is, to be very, very kind, questionable.

So, whereas previously, navicular disease was something that was pretty easy to diagnose and treat, all of a sudden, pretty much everything that veterinarian’s thought they knew turned out to be wrong. After about fifty years, we’ve at least figured THAT out.

Unfortunately… people tend to have long memories. So, even today, horses get quickly diagnosed with navicular disease, based on a simple series of steps, and they get treated with a drug that’s almost certain not to work. There are new drugs, too – and there’s good reason to believe that they don’t do much, either. But the kicker is: the horses still get better. Of course – and you know this, having read this far – the reason that some of these horses get better is they didn’t have the problem in the first place. They got better in spite of their treatment, not because of it. The problem still persists in the prepurchase arena, too, where good sound horses can get condemned for having “pre-navicular” or “navicular changes” when, in fact, there’s no evidence that these horses have – or will have – any problem at all.

Unfortunately… people tend to have long memories. So, even today, horses get quickly diagnosed with navicular disease, based on a simple series of steps, and they get treated with a drug that’s almost certain not to work. There are new drugs, too – and there’s good reason to believe that they don’t do much, either. But the kicker is: the horses still get better. Of course – and you know this, having read this far – the reason that some of these horses get better is they didn’t have the problem in the first place. They got better in spite of their treatment, not because of it. The problem still persists in the prepurchase arena, too, where good sound horses can get condemned for having “pre-navicular” or “navicular changes” when, in fact, there’s no evidence that these horses have – or will have – any problem at all.

So, look, if your horse gets diagnosed with navicular disease, or if your horse gets rejected on a prepurchase exam, don’t necessarily despair. Make sure that it’s a diagnosis that’s arrived at carefully. Make sure that your horse gets plenty of time off to allow other things in his foot to heal; a good number of problems related to the foot will heal with time (and may be assisted by good shoeing). And forget about the isoxsuprine, because it almost certainly can’t work.

And try to forget all that other stuff, too. Except….

Now there are new treatments for navicular disease (CLICK HERE to read about them). They’re being doled out like candy. They’re the latest. We’ll see how that goes, I guess. If history is any example, memories will likely persist, at least until the next new opportunity to make one comes along.

******************************************************************************************************************************

* For those of you who, like me, are word freaks, the word “navicular” dates back to 1540; navicular means “boat-shaped,” which sort of describes the shape of the bone.

** I once saw a horse that had eaten a 50 pound bag of rat poison. Didn’t affect him a bit. Turns out that the dose of warfarin needed to kill a horse is LOTS more than is in a 50 pound bag of rat poison. Not that I’d recommend feeding 50 pounds of warfarin-based rat poison to your horse, but it won’t hurt him.