I love history. I think it’s really important. And I think it’s really sad when history gets misstated, or distorted, and especially so when that distortion is used to sell something to people.

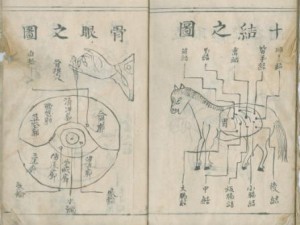

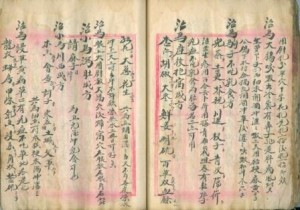

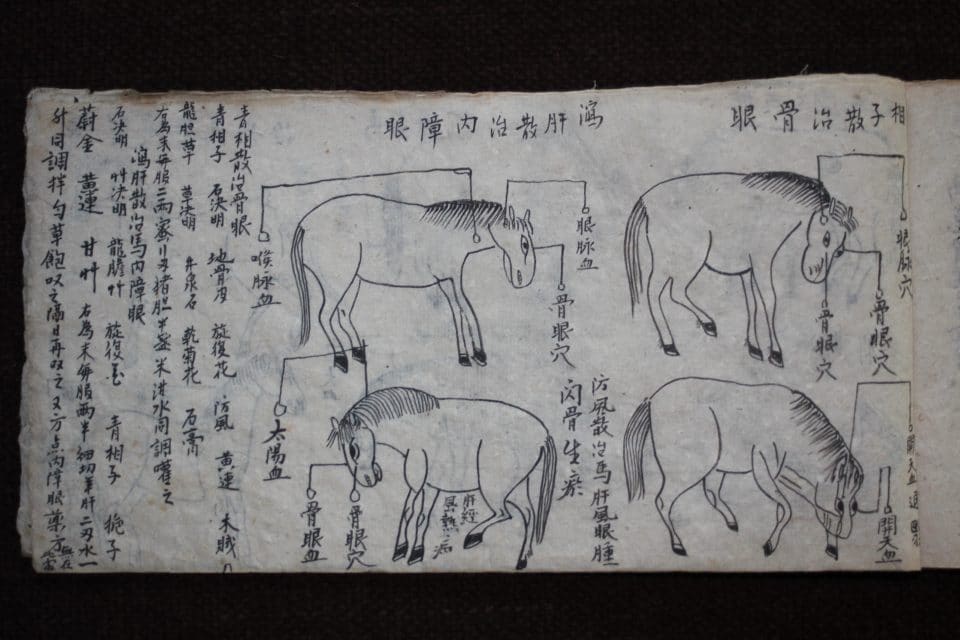

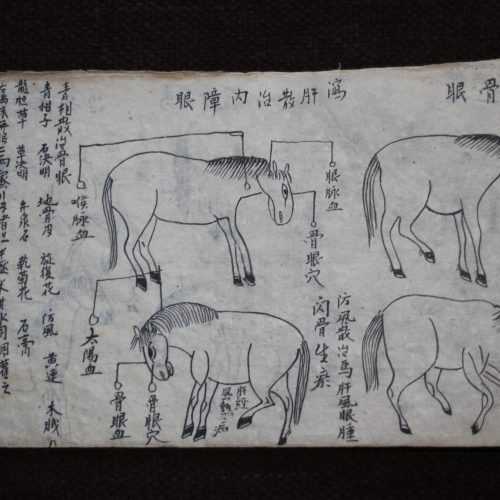

Over the past couple of decades, I have loved learning about the history of veterinary medicine in China. China has a rich tradition of treating animals, mostly horses, camels, and water buffalo.* As part of that interest, I accumulated about 3 dozen hand-written manuscripts from China, some dating to the 18th century. These manuscripts are a record of what practitioners REALLY did to animals in China. I’ve had parts of some of them translated, which has also resulted in several articles on the history of horse medicine in China, a couple of which you can read if you CLICK HERE. You can also see a slide presentation that I gave at the American Veterinary Medical Association Convention in 2011 on the subject.

Over the past couple of decades, I have loved learning about the history of veterinary medicine in China. China has a rich tradition of treating animals, mostly horses, camels, and water buffalo.* As part of that interest, I accumulated about 3 dozen hand-written manuscripts from China, some dating to the 18th century. These manuscripts are a record of what practitioners REALLY did to animals in China. I’ve had parts of some of them translated, which has also resulted in several articles on the history of horse medicine in China, a couple of which you can read if you CLICK HERE. You can also see a slide presentation that I gave at the American Veterinary Medical Association Convention in 2011 on the subject.

Instead, what the “TCVM” advocates have come up is a modern fairy tale – loosely based on a selected few historical theoretical concepts, and fine-tuned for western sensibilities – that has essentially no foundation in how veterinary medicine was actually practiced in China. Not only are these “TCVM” proponents inventing nonsense, but they’re trivializing, obscuring, and covering up a very interesting, real, and as yet largely undocumented, chapter in veterinary history. The same thing has gone on in human medicine – if this sort of thing interests you, I’d suggest taking a look at the book, “Neither Donkey nor Horse.”

![Pferd_ch[1].Buch003 Pferd_ch[1].Buch003](https://www.doctorramey.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/Pferd_ch1.Buch003-300x160.jpg) I really do think that the distortion of history in the name of the “traditions” of China is a terrible problem. A few “TCVM” proponents have infiltrated a couple of major university faculties. That means a few select faculty members are teaching students nonsense, and students are graduating having learned it. Some have even set up “schools” to certify people in “TCVM,” which is really just a modern fairy tale. (Of course, I don’t really thing much of “certification” in general – CLICK HERE to find out why.) But as a result of decades of misinformation, fabrication, and promotion, there’s now a subset of the population who thinks that they’re treating, or getting treatments for, animals based on the “wisdom” of Chinese historical traditions.

I really do think that the distortion of history in the name of the “traditions” of China is a terrible problem. A few “TCVM” proponents have infiltrated a couple of major university faculties. That means a few select faculty members are teaching students nonsense, and students are graduating having learned it. Some have even set up “schools” to certify people in “TCVM,” which is really just a modern fairy tale. (Of course, I don’t really thing much of “certification” in general – CLICK HERE to find out why.) But as a result of decades of misinformation, fabrication, and promotion, there’s now a subset of the population who thinks that they’re treating, or getting treatments for, animals based on the “wisdom” of Chinese historical traditions.

But they aren’t.

“What’s that?” you say. “Surely the Chinese treated animals?”

Well, yes, they did, but not in anything like the modern fairy tale crafters behind “TCVM” would have you believe. In all of the mind-numbing propaganda that’s been foisted on the public in an effort to portray Chinese veterinary medicine as natural, at one with the cosmos, etc., etc., a few things stand out. Mind you, this isn’t everything – I’m just picking out a few pretty bad examples. Here we go.

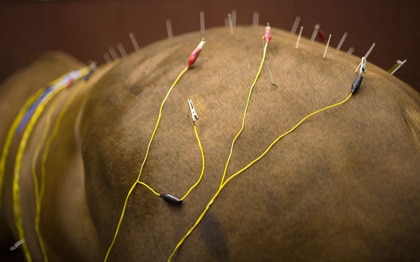

1. ACUPUNCTURE WAS NEVER A PART OF THE CHINESE TRADITION OF TREATING ANIMALS. The Chinese simply didn’t do acupuncture, not in the modern sense of the word (fine needles, specific points, along “channels: – that sort of thing). They did occasionally intervene at “points” – the cut horses at points, they bled horses at points, and they burned horses at points (with hot irons): just like every other culture. But the Chinese didn’t use fine needles, they didn’t associate the points along special channels.

1. ACUPUNCTURE WAS NEVER A PART OF THE CHINESE TRADITION OF TREATING ANIMALS. The Chinese simply didn’t do acupuncture, not in the modern sense of the word (fine needles, specific points, along “channels: – that sort of thing). They did occasionally intervene at “points” – the cut horses at points, they bled horses at points, and they burned horses at points (with hot irons): just like every other culture. But the Chinese didn’t use fine needles, they didn’t associate the points along special channels.

Talking about acupuncture as being part of a long tradition is done to infer that it’s effective. That is, if it’s been around for so long, it must be useful (using the same line of reasoning, astrology has long since proved it’s worth, by the way). Nevertheless, the idea that acupuncture must be effective because it’s been used for so long is simply wrong for two reasons. First, because it hasn’t been used for very long. And second, it hasn’t been shown to be effective for curing anything.

2. THE “TRADITIONS” OF CHINESE MEDICINE DIDN’T IMPROVE OVER TIME.

Another TCVM fiction is that the Chinese refined their treatments over time. That is, over thousands of years, they systematically discarded what didn’t work, and kept what worked. Sort of Darwinian approach to therapy, as it were.

Sounds good, except…. it didn’t happen. Among the many things that ancient cultures were not known for were 1) The ease of dissemination of information, and 2) Literacy. Most people were born and died in pretty much the same place. Information didn’t travel easily: no cell phones, FAX machines, or telegraphs. Sure, there were occasional books. A few of them survive in some form (having been changed and revised over the years), but they weren’t widely read; they couldn’t have been widely read. People didn’t travel, printed books weren’t available, and most people couldn’t have read them anyway. As such, for most of history, medicine – the medicine of all cultures, not just China – relied on individual oral and family traditions, as opposed to study and refinement.

3. ANIMALS DIDN’T GET TREATED ACCORDING TO THEORY – ANY THEORY. The veterinary medicine of China was very pragmatic. They saw a problem – they treated the problem. So, for example, when confronted with a horse with colic, they recognized that the horse wasn’t defecating, and they attempted to remove feces from the rectum at one of several internal “points.” They even illustrated the points where the manure was supposed to be accumulating (they didn’t dissect horses to learn the internal anatomy). However, modern “TCVM” folks apparently decided that these points of manure accumulation were acupuncture points: they wouldn’t have had that problem if they had read the original text.

Here’s one of the first treatments described in Chinese veterinary medicine, from the 6th century Qiminyaoshu: “Recipe for treating contagious disease of cattle or horses: Take otter feces. Decoct and drench the animal. Otter meat and liver are [also] good. If one cannot obtain otter meat or liver, just use feces.”

There’s Chinese medicine in the “traditional” sense.

4. TREATMENT OF ANIMALS WAS NOT “HOLISTIC,” IN ANY SENSE OF THE WORD. This idea that the Chinese treated animals “holistically” is just silly. The Chinese viewed animals as “things.” ** When they saw a problem in animals that they cared about (mostly horses, camels, and oxen), they treated the problem: mostly by burning them, or bleeding them or giving them some plant or mineral. They didn’t worry about being at one with the universe, or “five phases” or any of the mystical musings that NEVER were part of veterinary medicine, and only a very minor part of medicine for people.

Look, I’m not trying to say that the ancient Chinese people who treated animals were dumb or anything. The historical practitioners of Chinese medicine did the best they could. So did everyone else who treated animals – and treated people for that matter. However, in every historical culture that was trying to treat illness, the practitioners of medicine just didn’t have any idea what was going on, that is, they didn’t know the basis of real underlying causes of disease. It must have been very frustrating – even as veterinary medicine can sometimes be today, even with all of the tools at our disposal.

Still, historical medical practitioners had to have something with which to explain the scary processes of disease, illness, and death. So, people believed in things like evil spirits and bad humours. The Chinese thought that your dead ancestors were very influential on your health. People prayed, sacrificed, burned, purged, bleed, poked, ate plants, sat in salt mines, and did myriad other wild, crazy, and sometimes desperate things to try to improve their health and cure disease (the history of medicine is really quite eye-opening).

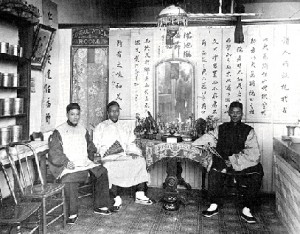

Chinese medical clinic, Chinatown, San Francisco, 1890’s. CLICK HERE for an interesting article on 19th century medical self-help in Chinatown.

My point is that every culture has its traditions. And, up until the turn of the 20th century, all of the traditions had one thing in common: their treatments mostly didn’t work. Human life expectancy, in every studied culture, throughout history, no matter what the philosophy of the treating doctors, was about 40 years. So, by arguably the most important measure of health – longevity – exactly none of the “traditional” approaches to medicine did much good, whether you were following cultural traditions, local healers, or the advice of the doctors of the time. And there’s a good reason for this.

HERE’S THE REASON: For most of history, nobody really knew what they were treating.

So, given that, you might wonder, “Why even bother with traditions?” whether from China, or somewhere else? I mean, we don’t really celebrate the traditions of communication by maintaining telegraphs in the kitchen so that we can stay in touch with our friends through Morse Code, right? We don’t celebrate the traditions of plumbing by keeping an outhouse in the backyard. We don’t celebrate the traditions of transportation by hauling our goods around in ox carts.

BOTTOM LINE: It’s kind of hard for me to figure out why some people so excited about a “tradition” of medicine when 1) It didn’t cure or prevent disease, and 2) As is the case with the modern “TCVM” fairy tale, it never existed anyway.

An illustrated page from the 1824 manuscript on Chinese Horse Medicine – CLICK HERE to learn more.

***********************************************************************************************************

*Small animals weren’t valued in China, except as food – actually, small animals were considered vermin. There’s no Chinese historical tradition of treating small animals.

** That’s a direct quote, from a 13th or 14th century text (nobody knows for sure) called the Simu Anji Ji

![Pferd_ch[1].Buch002 Pferd_ch[1].Buch002](https://www.doctorramey.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/Pferd_ch1.Buch002-300x154.jpg)