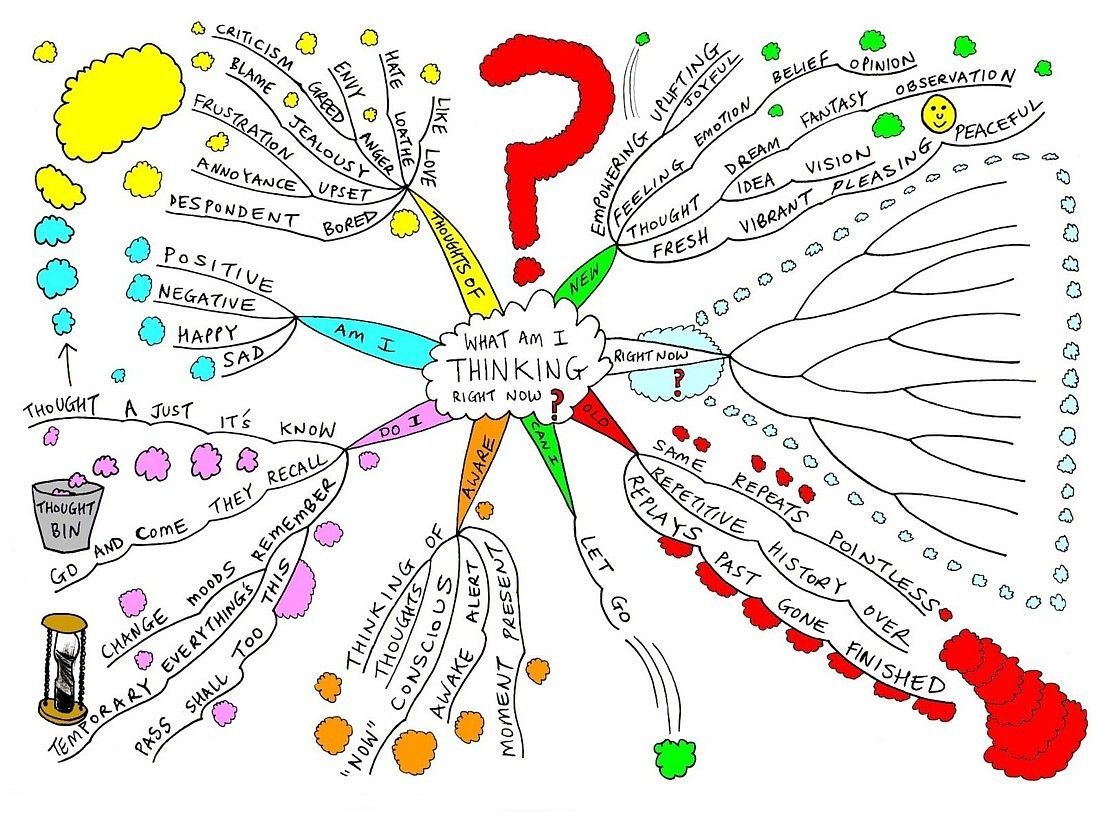

One of the things that I find interesting is the field of epistemology. In case that’s not something that you’re familiar with, epistemology is the study of knowledge, that is, the study of why is it that we think we know what we know. I’m also fairly introspective. I like to think and ponder and let me mind race off chasing all sorts of ideas that jump into my head, usually unexpectedly.

One of the things that I find interesting is the field of epistemology. In case that’s not something that you’re familiar with, epistemology is the study of knowledge, that is, the study of why is it that we think we know what we know. I’m also fairly introspective. I like to think and ponder and let me mind race off chasing all sorts of ideas that jump into my head, usually unexpectedly.

One of the things that’s been nagging at me lately is the question of how I came to think about horses the way that I do. I mean, clearly, I went to vet school, and I’ve read and studied a lot, but it’s not my knowledge about horses that I’m writing about this time. It’s the approach that I take to their care. I started thinking, “Why is it that I think about horses and horse medicine the way that I do?” I came up with five main answers.

- I wasn’t raised around horses

- I have a degree in Animal Science

- When I was in college, I took care of my own horse

- Clovis and I did everything together

- I think it’s wrong to take advantage of people

So let’s have some fun with those answers.

For a couple of years, when was was 6 to 8 years old, a had a pinto pony. He was, as near as I can remember, a small pony. As is apparently imperative for many paint ponies, he had a native American name: we called him, “Apache.” We kept him on a small farm near the Ohio River in western Kentucky. I rode him pretty much everywhere: around the farm. through ditches, running through cornfields, falling off when he jumped over things when I wasn’t expecting it. Pretty idyllic stuff, actually. And then we moved: left Apache on the farm. I I didn’t touch horses again for another decade or so (that’s another bunch of stories).

So how was this so formative? Well, I think in two ways (if you haven’t noticed in reading my stuff by now, I like lists).

First, it ingrained a love of horses in me. That is, when I was a little boy, I just loved being around my pony and having fun with him. That’s really never left me. I STILL love being around horses and having fun with them.

I don’t think that love of horses established at a young age ‘s particularly unique, however. Which brings up the second thing. As much time as Apache and I spent together, I really wasn’t around anyone who told me how I had to do anything. I’m quite confident that I made one mistake after the other, but, fortunately, Apache never seemed to suffer from my apparent lack of knowledge of how things were “supposed” to be done. Apache, by the way, lived well into his 30’s, apparently unscarred by having had a young owner who wasn’t filled with presuppositions.

I really do think that this lack of introduction into the way things “have” to be done left me somewhat unprepared for all of the well-meaning but ultimately baseless information that’s rampant in the horse world. For example, as an 8-year-old I never eagerly learned (as 8 year-old’s do) that was important to wrap a limb clockwise or counter-clockwise (it doesn’t matter, but I’ve certainly run into firm opinions on both directions). Instead, being almost 19 years old when I decided I wanted to be a veterinarian for horses, I tended to ask, “Why” when confronted with information that didn’t make sense (you know how 19 year-old’s are).

That tendency to ask, “Why” has stayed with me over my career. And now, when I see something that doesn’t make sense, I’m more than happy to write about it.

I HAVE A DEGREE IN ANIMAL SCIENCE

Once I decided that I wanted to go to veterinary school, I had to switch my major (my first year in college, I was a political science major). I figured that there would be no better major for me than Animal Science. And I was right – for me, it was great. It led to a lot of great stories and memories (and admission to veterinary school).

But I digress. A good bit of animal science involves studying production animals: for things like meat, milk, and eggs. While we can certainly have a lively discussion about how such animals are treated – and when I went to school, such discussion weren’t nearly as common as they are now – the fact is that for producers of animal products, cost and efficiency are WAY up on the scale of importance. Producers want to produce a healthy product, but they also want to do it as efficiently as possible, and at the lowest cost. Thus, some of my animal science background was spent trying to come up with things like least cost rations for dairy cattle, that is, feed programs that could both nourish the cows and not ruin the bank account of the cow’s owner. They keep careful track of such things. They do science. I like that.

But I digress. A good bit of animal science involves studying production animals: for things like meat, milk, and eggs. While we can certainly have a lively discussion about how such animals are treated – and when I went to school, such discussion weren’t nearly as common as they are now – the fact is that for producers of animal products, cost and efficiency are WAY up on the scale of importance. Producers want to produce a healthy product, but they also want to do it as efficiently as possible, and at the lowest cost. Thus, some of my animal science background was spent trying to come up with things like least cost rations for dairy cattle, that is, feed programs that could both nourish the cows and not ruin the bank account of the cow’s owner. They keep careful track of such things. They do science. I like that.

My animal science degree has stuck with me, I think. So, when I see a horse, I’m thinking about things other than simply what can be done. I tend to look at horse owners in the same way that I looked at owners of production animals. Production animal owners want healthy animals, but they also want them at the lowest cost. They’ll pay more for things that make the animals better, but the don’t want to pay for fluff. For better or worse, that’s how I’ve approached my job. Imagine: healthy horses without breaking the bank.

WHEN I WAS IN COLLEGE, I TOOK CARE OF MY OWN HORSE

WHEN I WAS IN COLLEGE, I TOOK CARE OF MY OWN HORSE

Most folks that have had a college experience remember it fondly, I think. However, most don’t remember it being the high times of their financial lives. Mine was no exception. I took classes, had fun, and took care of my horse, Clovis, too. I boarded him at a friend’s house. Had to throw him hay in the winter and break ice in the trough sometimes. I tried to save money constantly, but throw in shoeing and the occasional veterinary visit and the money that I earned working on weekends and after school wasn’t hard to spend.

I sure couldn’t afford to waste money, no matter how much I loved Clovis. I guess I think back to me as a college student when I think about the horse owners that I’m working for.

CLOVIS AND I DID EVERYTHING TOGETHER

Look, I understand that horses have value: sometimes, a LOT of value. That doesn’t have anything to do with horses being horses.

Horses love to do – and can do and enjoy doing – all sorts of things. So Clovis and I entered endurance riding competitions. We did the vet school rodeos. We went on trail rides. We jumped the cross-country course behind Horsetooth Reservoir. We went swimming. We did the Park City, Utah, Ride and Tie (it was grueling, but we got through it). We played. We had fun. We won some – and we lost some. We always worked together. He was worth at least his weight in gold.

Horses love to do – and can do and enjoy doing – all sorts of things. So Clovis and I entered endurance riding competitions. We did the vet school rodeos. We went on trail rides. We jumped the cross-country course behind Horsetooth Reservoir. We went swimming. We did the Park City, Utah, Ride and Tie (it was grueling, but we got through it). We played. We had fun. We won some – and we lost some. We always worked together. He was worth at least his weight in gold.

I think that’s why I shudder when I think of horses being cooped up in a stall, being “too valuable” to let play, asked to perform under a strict set of rules. I mean, they’ll do it, but they’ll do it more willingly if they’re allowed to be horses. Ask Charlotte Dujardin. Or Richard Spooner.

Even valuable horses are lots of fun to play with. That’s the way it should be with all of them. For one thing, they have no idea how much they are worth. They’re “just” horses.

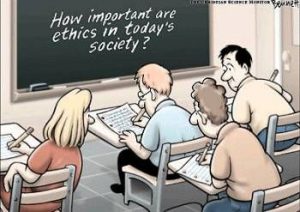

I THINK IT’S WRONG TO TAKE ADVANTAGE OF PEOPLE

Lastly, there’s this ethics thing. I am in the perfect position to take advantage of people. I have a degree, I have a license, and I know a whole lot about horses. This puts me in a perfect position to take complete advantage of people who, not having a license or a degree, and not knowing much about horses, trust me.

But I think it’s wrong to do that. That’s why I think it’s so important to have a foundation of truth and scientific knowledge behind anything that I do. I don’t think it’s OK to just try stuff on someone’s horse just because I can: just because I’m in a position of authority. I don’t think that I should push products that aren’t supported by evidence on people. They’re counting on me. Their horses are counting on me, too. I’m not the only one who feels that way – I know a whole bunch of colleagues who feel exactly the same way. That ethical thing is really important.

But I think it’s wrong to do that. That’s why I think it’s so important to have a foundation of truth and scientific knowledge behind anything that I do. I don’t think it’s OK to just try stuff on someone’s horse just because I can: just because I’m in a position of authority. I don’t think that I should push products that aren’t supported by evidence on people. They’re counting on me. Their horses are counting on me, too. I’m not the only one who feels that way – I know a whole bunch of colleagues who feel exactly the same way. That ethical thing is really important.

So, there you go. For better or worse, that’s where I’m coming from. We’re over 20,000 on Facebook, all trying to help horses. Thanks for coming along for the ride.