Lucky Horse

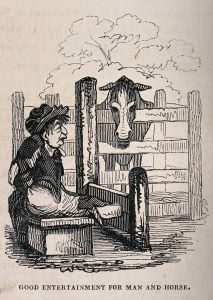

If you have your horses where they can hang out with their buddies in big grass pastures, good for you. Good for them, too. Horses are social creatures. They are very curious about other horses and love to hang out with them. They’re mobile creatures; in the wild, they roam freely, covering 25 to 50 miles per day. They eat in 23 of 24 hours a day (they came up with the phrase, “Eating like a horse,” for a reason). If you can keep your horse like that, you’re lucky and they’re lucky.

Unfortunately, not every horse – not every person – is so lucky. Whereas, say, a few hundred years ago, houses were fairly few and far between, now there are whole collections of them: cities, and big ones. Just because people started living in big cities didn’t also mean that they stopped loving horses. So now, some horses are housed primarily in box stalls.

Not bad, for a stable!

There are reasons urban horses live in boxes. It’s more practical – it’s a lot easier to set up a time to come see and ride and hang out with a horse when you know exactly where he’s going to be. It’s safer for the horse, too, that is, it’s safer for him to be in a box than it is for him to be roaming around the streets and freeways. Horses in box stalls tend to get pampered, as well. They usually get regular good food, and brushing, and blankets, and toys and all sorts of other things that make people feel good: maybe horses, too. In some respects, living in a box is likely better than having to look for a patch of grass in an arid desert while keeping an eye open for predators.

Nevertheless, the fact of the matter is that horses aren’t really made to be in boxes. It’s not the way that they’d prefer to live. As such, housing horses in stalls raises concerns as to their welfare.

Most people are aware of these problems. Keeping horses in boxes restricts the horse’s ability to move. It also restricts their social interactions with other horses. Horses in box stalls usually only get fed once or twice a day. It shouldn’t be controversial to say that boxes are not optimal conditions in which to keep horses, at least as far as the horses are concerned.

Most people are aware of these problems. Keeping horses in boxes restricts the horse’s ability to move. It also restricts their social interactions with other horses. Horses in box stalls usually only get fed once or twice a day. It shouldn’t be controversial to say that boxes are not optimal conditions in which to keep horses, at least as far as the horses are concerned.

Some horses seem to adapt to boxes fairly well (although there still may be some very valid concerns). Others: not so much. Horses that don’t like living in boxes usually show their displeasure through (usually only) one of four types of behavior indicators. These are (in no particular order):

- Aggressiveness towards humans, or hyper-vigilance, that is, where they seem to react to most any- or everything.

- Unresponsiveness to environmental stimuli (e.g., a “withdrawn” posture, where they don’t react to much of anything)

- Stereotypies (e.g., stall weaving, cribbing, wind sucking, that is, behaviors that are repetitive and unchanging, and that have no obvious goal or function other than to drive their owners crazy)

- Stress-related behaviors or diseases, such as gastric ulcers or colic

SOLUTIONS?

www.savagechickens.com

Most horse owners are aware that keeping a horse in a box isn’t necessarily the best thing for the horse’s mental well-being. That awareness is a good thing and it leads many people to try to do things to help their horses cope with the stress. In general, the things that people try to do to help horses cope with their boxes fall into four main categories.

- Housing system features, such as the choice of bedding material, putting a barred window between stalls, or allowing the horse to face outside.

- Feeding factors, such as the amount of hay, the amount of concentrate fed per day, the number of times per day fed, etc.

- Factors related to the type of equitation practices, e.g., changing things up for the horse, or even the specific discipline

- The intensity of the physical activity in which the horse participates, such as the time spent being ridden per week

AN INVESTIGATION

Recently, investigators have looked into such interventions. On-line, there’s an interesting journal called, “Animals.” You don’t have to subscribe to it to read it – such journals are called “Open Access” journals. Here’s a link to the original article, which looked into commonly prescribed solutions to stall-related stressors, and their effectiveness (Ruet, A., et al. Housing Horses in Individual Boxes Is a Challenge with Regard to Welfare. August, 2019. https://www.mdpi.com/2076-2615/9/9/621).

Recently, investigators have looked into such interventions. On-line, there’s an interesting journal called, “Animals.” You don’t have to subscribe to it to read it – such journals are called “Open Access” journals. Here’s a link to the original article, which looked into commonly prescribed solutions to stall-related stressors, and their effectiveness (Ruet, A., et al. Housing Horses in Individual Boxes Is a Challenge with Regard to Welfare. August, 2019. https://www.mdpi.com/2076-2615/9/9/621).

A total of 187 horses were investigated. These horses were stabled, and they did not have access to paddocks or grazing turnouts. The horses were observed five times daily by a single observer over 50 non-consecutive days during a a nine-month period.

RESULTS

To me, two things stood out in the study. First, most of the attempts to mediate stress in the horses didn’t appear to do anything, at least, they didn’t change how the horses expressed stress. Second, those things that did appear to do something didn’t have very profound effects, that is, they didn’t completely alleviate the stress of living in a box. Here’s some things that they found that didn’t make any difference.

- There was no difference observed between stallions, mares, or geldings.

- Older horses seem to demonstrate stress-related behaviors more than younger ones.

Increasing physical activity through riding, by lunging, or but putting horses on a mechanical walker, did not seem to do much to reduce stress (on the horses – there’s no telling what effects having to increase physical activity might have on the riders).

Increasing physical activity through riding, by lunging, or but putting horses on a mechanical walker, did not seem to do much to reduce stress (on the horses – there’s no telling what effects having to increase physical activity might have on the riders).- The regularity of the training, or how many shows that a horse went to in the nine-month period didn’t make a difference.

- The time spent being ridden or trained didn’t seem to matter to the horses, insofar as stress-relief.

- Equitation-related factors, such as the discipline in which the horse competed and the level of performance had no significant effect on the measures of welfare.

- Providing a grilled window in a stall did not appear to help relieve stress. You might think that having a frilled window in the stall might help by allowing a horse to stay in closer contact with his neighbor, however, if there was an effect, it wasn’t seen.

On the downside, there was a direct relationship between the amount of time horses spent in their stalls and the likelihood that they would be unresponsive to their environment. That is, the more time that horses spend in their stalls, the more depressed they seem to be. Go figure.

DID ANYTHING HELP?

Well, yes, maybe a little. There are definitely things that can be done to help a horse who lives in a box stall feel better about life.

- Free exercise

- Allowing stabled horses to interact with other stabled horses

Allowing horses to eat fibrous feeds as much as possible

Allowing horses to eat fibrous feeds as much as possible- Straw bedding. Straw bedding seemed to invite horses to lie down and explore their environment. Horses may also eat straw, which is not necessarily a bad thing, nutrition wise. Plus, it gives them something to do.

- A window or stall door that opens onto the external environment lets horses look outside and see other horses. Horses like seeing other horses, and when they can, it seems to decrease their tendency to be aggressive, both towards other horses and towards humans.

- Less grains and concentrates. At this point, there really shouldn’t be any disagreement with the idea that grains and concentrates are mostly no good for horses. Lots of concentrated feed makes the stomach secrete gastric acid. If you combine lots of grain with low amounts of forage, you end up with stomach irritation, ulcers, and even undesirable behaviors, such as cribbing or stall weaving.

I think that it’s important to do as much of these sorts of thing as you can for your stalled horse. Unfortunately, even if you do them all, they seem not to completely override the more negative effects of stall confinement.

CONCLUSIONS

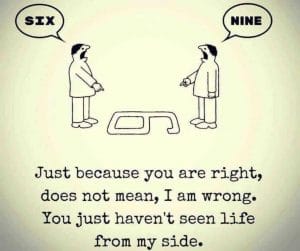

I think it’s important to keep all of this in perspective. There is no perfect world. In fact, it’s usually annoying when people try to make everything perfect. As Confucius said, “Better a diamond with a flaw than a pebble without.” Personally, I think that the world is a better place with horses in it, even if they don’t always get to roam free, with plenty to eat, free of predators (come to think of it, when did they ever get to have that?).

Still, on some level, it’s pretty inarguable that keeping a horse cooped up in a box can be detrimental to his overall welfare. Plus, the more time that horses spend in boxes, the worse things are for them. Furthermore, the longer horses spend in stalls over their lifetimes, the more likely it is that they become unresponsive to their environment: older horses are more likely to demonstrate such unresponsiveness than are younger horses. Who knows, this might be analogous to depression in people.

Still, on some level, it’s pretty inarguable that keeping a horse cooped up in a box can be detrimental to his overall welfare. Plus, the more time that horses spend in boxes, the worse things are for them. Furthermore, the longer horses spend in stalls over their lifetimes, the more likely it is that they become unresponsive to their environment: older horses are more likely to demonstrate such unresponsiveness than are younger horses. Who knows, this might be analogous to depression in people.

Even though the study shows that many things that people do to try to help stalled horses cope with the stress of confinement aren’t that effective, it certainly doesn’t mean that you shouldn’t try them. For example, no matter how much stress it relives, horses need regular exercise and it’s good for them. If they have to live in stalls, it’s a good idea to try to get them to spend time in a larger area: ideally with other horses. Horses give so much to us – we should try to do everything that we can to help make their lives better, too.