At this point, I’ve kind of lost count of the number of horses that I’ve examined for people that are interested in purchasing a horse. Prepurchase exams have been sort of a staple ever since I started practicing. I’ve been fortunate enough to get to examine horses with values from several hundred dollars to several million Euros, all over the US, Europe, and Canada, from backyard companions to international level jumping and dressage horses, and pretty much everything in between. I’d guess that, at this point, I’ve done somewhere between 2000 – 3000 such exams. Mostly, that means I’ve been lucky enough to practice in the right place, at the right time, and for the right people. But I also think that it’s given me a bit of insight into the whole procedure, and I thought I’d share a few thoughts.

At this point, I’ve kind of lost count of the number of horses that I’ve examined for people that are interested in purchasing a horse. Prepurchase exams have been sort of a staple ever since I started practicing. I’ve been fortunate enough to get to examine horses with values from several hundred dollars to several million Euros, all over the US, Europe, and Canada, from backyard companions to international level jumping and dressage horses, and pretty much everything in between. I’d guess that, at this point, I’ve done somewhere between 2000 – 3000 such exams. Mostly, that means I’ve been lucky enough to practice in the right place, at the right time, and for the right people. But I also think that it’s given me a bit of insight into the whole procedure, and I thought I’d share a few thoughts.

I think that, for starters, there are a lot of unreasonable expectations when it comes to the veterinarian’s role in someone’s purchase of a horse. I think that, on the one hand, a lot of horse buyers go into a prepurchase exam thinking that having the horse examined by the veterinarian is going to protect them from a bad purchase (however one might define such a thing). On the other hand, I think that I lot of veterinarians go into prepurchase exams looking for reasons why a client shouldn’t buy a horse, under the general feeling that it’s better to make a recommendation to pass on a purchase, and avoid potential repercussions, than it is to say that a horse seems OK, and risk the wrath of a client (or worse, an attorney) somewhere down the line,

NOTE: I had a lawsuit filed against me years ago when a horse that I examined 2.5 years previously went lame after 2.5 years of a successful high level jumping career. The case got thrown out, but you can’t protect yourself against stupidity.

Now, it’s not like I know nothing about horses. I can certainly tell you a few things about a horse, and with a good bit of certainty.

Now, it’s not like I know nothing about horses. I can certainly tell you a few things about a horse, and with a good bit of certainty.

- The sex (I mean, I did go to veterinary school, although this is not a prerequisite)

- The color

- How he is to handle on the ground, at least on that day, and in that setting (NOTE: This is important – he may act differently when he’s not at home)

- His age, within a fairly wide range of error (see below)

- Whether or not he is showing signs of lameness today

- Whether or not he is showing other signs of physical problems today

And, to be honest, that’s about it.

What’s at least as important in the buying process (at least in my opinion), is what I can’t tell you. It’s a lot, and some of it isn’t even my responsibility. The fact is that when you buy a horse, you’re taking a risk that things aren’t going to work out (of course, the other side of the coin is that you might be making the best purchase you’ve ever made). If you understand what a veterinarian can’t tell you during a prepurchase exam, then maybe it will help you into a prepurchase exam with reasonable expectations, and maybe you’ll feel like you have a bit more control over the whole process. Here goes.

I CAN’T TELL YOU IF YOU’RE GOING TO LIKE THE HORSE

This could sound a bit silly, but trust me, if you’re thinking about buying a horse, you should spend as much time as you can seeing if you actually like hanging out with him. I’ve seen plenty of people buy horses that bite, kick, spook, or strike because they have “potential” or they think that they, or someone that they hire (often the person recommending they buy the horse), can train the behavior out of the horse. Maybe you (or they) can.

This could sound a bit silly, but trust me, if you’re thinking about buying a horse, you should spend as much time as you can seeing if you actually like hanging out with him. I’ve seen plenty of people buy horses that bite, kick, spook, or strike because they have “potential” or they think that they, or someone that they hire (often the person recommending they buy the horse), can train the behavior out of the horse. Maybe you (or they) can.

I once looked at an unbroke 7-year-old stallion. A lady was buying the horse for her 7-year-old son. She wanted them to grow up together. I asked if she wanted her 7-year-old to grow up at all. The horse had no physical problems, but the fact that she couldn’t put a halter on the horse, much less handle him, seemed to have been lost on her.

You’re going to be in this relationship for a while – like any other relationship you are thinking about getting into, you might want to spend some time finding out if you really like the horse before taking the plunge.

I CAN’T TELL YOU IF HE’S GOING TO STAY SOUND

From decorated Olympians to backyard trail riders, most everyone buys a horse because they want to ride him in some capacity. I do not need to extoll the virtues of horseback riding here (it’s been studied, too). However, the fact of the matter is that when you ride a horse, you increase the risk or injury. And, the more strenuous the riding, the greater the risk. A long time ago, I flew to Arizona to look at a very nice jumping horse. He never took a lame step and his radiographs were perfect. He broke his previously perfect navicular bone going over a fence the next day.

From decorated Olympians to backyard trail riders, most everyone buys a horse because they want to ride him in some capacity. I do not need to extoll the virtues of horseback riding here (it’s been studied, too). However, the fact of the matter is that when you ride a horse, you increase the risk or injury. And, the more strenuous the riding, the greater the risk. A long time ago, I flew to Arizona to look at a very nice jumping horse. He never took a lame step and his radiographs were perfect. He broke his previously perfect navicular bone going over a fence the next day.

Think of cars. If you buy one and just drive it a few blocks to the grocery store a couple times a week, the risk of an accident is far less than, say, if you decide to enter a car race somewhere. Horses are like that, too. The harder you rider him, the more often you ride him, the more likely is that he’s going to have a lameness problem. No amount of prepurchase expenditure (on X-rays, ultrasound, blood tests, etc.) is going to change that simple fact. For that matter, no amount of post-purchase expenditure (joint supplements, injections, etc.) is going to change it, either. Whether or not a horse stays sound depends far more on how you take care of him than it does on how he looked at the time you bought him.

I MOSTLY CAN’T TELL YOU HOW OLD HE IS

I MOSTLY CAN’T TELL YOU HOW OLD HE IS

There are very elaborate charts that have been made showing how you can tell a horse’s age by looking in his mouth. The ones you’re probably most familiar with were initially drawn around the start of the 20th century, but there are also charts, using other criteria, in Chinese and Japanese manuscripts that go back hundreds of years.

The thing that they all have in common is that they are demonstrably inaccurate. Some very interesting work done in the 1990’s in the UK showed that whether the teeth are examined by people, or according to data entered into a computer, once horses get past five or six years of age, the accuracy of your estimate goes down, and markedly so after age 11, where you’re going to be off on your age estimates by an average of +/- 2.5 years. (CLICK HERE and CLICK HERE if you want to read more.)

The bottom line is that unless you are buying a fairly young horse, or unless you can see breeding papers or a tatoo, looking in your horse’s mouth is not an accurate way to estimate his age. I should be able to tell you the difference between a 5-year-old and a 20-year-old (and I’ve seen 20-year-olds represented as 5-year-olds), but if you want me to tell you if a horse is really 14 or 15, it’s just not possible.

I CAN’T TELL YOU IF HE’S GOING TO STAY HEALTHY

I’m looking at the horse you want to buy on a particular day. I’ll be able to tell you if he has a fever, if his heart is beating normally (HINT: If he’s standing there looking at you, it probably is), or if his lungs are working. With a bit more investigation – say, a blood test, or an endoscopic exam – I can tell you if his kidney function is OK or if his upper airway is working normally.

I’m looking at the horse you want to buy on a particular day. I’ll be able to tell you if he has a fever, if his heart is beating normally (HINT: If he’s standing there looking at you, it probably is), or if his lungs are working. With a bit more investigation – say, a blood test, or an endoscopic exam – I can tell you if his kidney function is OK or if his upper airway is working normally.

What I can’t tell you is how long this collection-of-good-fortune-that-amounts-to-good-health will last. I once looked at a horse that passed his prepurchase exam with flying colors, but died of colic three days later. You pays your money and you takes your chances.

NOTE: The idiom “You pays your money, you takes your choice” first appeared in print in 1846 in the London magazine Punch. This is so much more than just a horse blog.

I CAN’T TELL YOU IF HE CAN DO WHAT YOU WANT HIM TO DO AND I CAN’T TELL YOU IF HE CAN DO MORE THAN HE’S CURRENTLY DOING

This one’s on you. It’s up to you (and your trainer, if you’re so inclined) to determine if this horse can do what you want him to do. Ride him. Try him. Check out his show record. See if you can get him on a lease with an option to buy. Take as much time as you can to make your decision. Then, maybe, you’ll have some idea of whether he can do what you want him to do.

This one’s on you. It’s up to you (and your trainer, if you’re so inclined) to determine if this horse can do what you want him to do. Ride him. Try him. Check out his show record. See if you can get him on a lease with an option to buy. Take as much time as you can to make your decision. Then, maybe, you’ll have some idea of whether he can do what you want him to do.

As far as the future, that’s even more of a crapshoot with horses. Horses are not aware that they have any potential at all. In fact, it’s mostly a miracle that they’ll do anything that we ask of them. Equestrian sports are the only team activity where half of the team doesn’t care how the team does, so don’t expect them to be working hard to ensure that they can reach their potential. At the end of the day, it’s all about what’s in the feeder anyway.

I CAN’T TELL YOU IF MOST X-RAY “CHANGES” ARE GOING TO AMOUNT TO MUCH

It seems to me that many buyers are looking at X-rays (radiographs, to use medical terminology) in an effort to tell if their purchase is going to work out. I understand the sentiment. The hope is that if you can look more deeply into a horse’s bone structure, you’ll have a better idea if the horse is going to stay sound for a while after you buy him. Mostly, that’s an illusion.

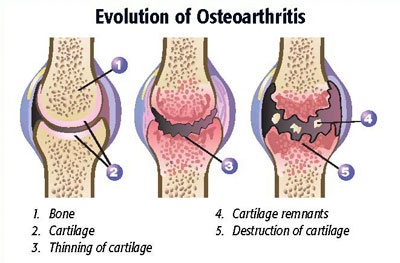

X-rays can be very useful in helping to determine is a horse’s lameness is due to some sort of problem in the bone (e.g., arthritis). That is, if the horse has a problem, they might help you be able to tell what it is.

X-rays can be very useful in helping to determine is a horse’s lameness is due to some sort of problem in the bone (e.g., arthritis). That is, if the horse has a problem, they might help you be able to tell what it is.

NOTE: If a horse has a problem on a prepurchase exam, it baffles me why anyone would want to spend money to find out what is wrong with someone else’s horse. If the horse isn’t OK at the time of exam, that’s really all you need to know.

X-rays are not crystal balls, however. It’s well known that radiographs of the navicular bone don’t predict future lameness (even though some people may assert that they do). Neck X-rays have become very popular recently, but the fact is that neck X-rays taken during prepurchase exams of normal horses don’t mean much and their predictive value for future problems is unknown. If you don’t buy an otherwise normal horse because someone thinks there’s a problem with the neck X-rays, there’s a pretty good chance that you’re just passing up the opportunity to buy a nice horse (CLICK HERE to read more).

In that same way, juvenile “bone chips” (osteochondral fragments) don’t necessarily have much significance. So, for example, it’s been shown that in yearling Thoroughbred racehorses, Radiographic findings in sales yearlings did not have an effect on total amount of money earned, amount of money earned per start, or whether horses placed in a race (CLICK HERE). In that same vein, such fragments in the hock don’t seem to affect performance in racing Standardbreds, either (CLICK HERE). It turns out that many sound warmbloods have them, too (CLICK HERE). My own personal feeling is that if you’re looking at a horse that’s been working successfully for a while, he’s going great when you buy him, and you happen to find a small chip on an X-ray, it probably doesn’t mean much.

In that same way, juvenile “bone chips” (osteochondral fragments) don’t necessarily have much significance. So, for example, it’s been shown that in yearling Thoroughbred racehorses, Radiographic findings in sales yearlings did not have an effect on total amount of money earned, amount of money earned per start, or whether horses placed in a race (CLICK HERE). In that same vein, such fragments in the hock don’t seem to affect performance in racing Standardbreds, either (CLICK HERE). It turns out that many sound warmbloods have them, too (CLICK HERE). My own personal feeling is that if you’re looking at a horse that’s been working successfully for a while, he’s going great when you buy him, and you happen to find a small chip on an X-ray, it probably doesn’t mean much.

Add to that the fact the opinion of the significance of a particular X-rays finding is going to vary widely between individual practitioners, and you’re got lots of room for disagreement as to the relevance of a particular X-ray finding anyway. Otherwise stated – and here’s a news flash – one person’s opinion may not agree with another’s (CLICK HERE). At the end of the day, you have to ride the horse – you can’t ride the X-rays.

AT THE END OF THE DAY

I do think it’s a good idea to have a horse looked at before you buy him, and especially if you’re inexperienced. Veterinarians can give you some good advice, but they’ can’t predict the future. But I think it’s even a better idea to take your time and spend as much time as you can with the horse before you buy him, to make sure you like him and to make sure that he can do what you want him to do. That’s way more important than my opinion, anyway.

LAST: Please check out my new book, “Lost Traditions: Horses and Horse Medicine in Pre-Modern Japan.” If you love horses, art, and history, you won’t be disappointed! CLICK HERE to look and order.