Vaccination is certainly one of the most important interventions in health (human, animal, fish, etc.) that has ever been invented. But not all vaccines for horses are equally effective. Given that in many areas, it’s time for spring shots in most areas, I thought I’d give you some information about individual vaccines, and how well they are likely to work.* And by “work,” I mean, how likely they are to actually prevent the disease that they are supposed to prevent.

DISCLAIMER: By no means should you read this article and then go our and ignore the advice of your veterinarian. He or she may be aware of some individual circumstances that might make certain vaccines more or less useful in your area. But with the information below, if nothing else, you can have a good discussion.

FIRST THING: Vaccination is the process whereby a horse can be made somewhat resistant to a particular disease.

SECOND THING: Vaccines are not an iron-clad guarantee that your horse won’t ever get sick with that disease.

Vaccines have enabled veterinarians to control and prevent many awful diseases, especially in the pet and livestock industries. However, while I know your horse is important to you, economically speaking horses are not as important as livestock or pets. That’s perhaps one reason why there hasn’t been a strong reason (read: RETURN ON INVESTMENT) to spend a lot of time on developing and testing vaccines. So, in many respects, the equine vaccine field has lagged behind other that of other species.

It’s actually pretty hard to determine how well – or even if – many equine vaccines work. That’s because, when compared to most every other species, there’s not much published data put out before vaccines are released, and not much data gets accumulated after the vaccines are out there. Otherwise stated, nobody really keeps track once the vaccines are released. That means that the sort of information you’d need to make a fully informed decision (effectiveness, rate of reactions, etc.) for your horse just isn’t available. In fact, such aftermarket oversight isn’t even required.

It’s actually pretty hard to determine how well – or even if – many equine vaccines work. That’s because, when compared to most every other species, there’s not much published data put out before vaccines are released, and not much data gets accumulated after the vaccines are out there. Otherwise stated, nobody really keeps track once the vaccines are released. That means that the sort of information you’d need to make a fully informed decision (effectiveness, rate of reactions, etc.) for your horse just isn’t available. In fact, such aftermarket oversight isn’t even required.

The rationale behind vaccination is pretty simple. You vaccinate your horse, you prevent a disease, right? To be perfectly honest, that’s not always the case (and not necessarily through any fault of the vaccine). Many vaccines simply claim to be an aid in the management of the disease, which can be quite a shock when your vaccinated horse still gets sick. The fact of the matter is that no vaccine is perfect. Using vaccinations to prevent disease should be just one part of an overall strategy to control disease in horses, a strategy that might also include such things as:

- Isolation of sick animals

- Keeping shared environments clean

- Quarantine of new animals brought onto a premise

There’s a lot more that can be said, of course, about the type of evidence that’s (not) available and such, but let’s get to the bottom line: which vaccines appear likely to be effective, based on the evidence we have.

EQUINE INFLUENZA (FLU)

In experiments, flu vaccines tend do pretty well at preventing disease caused when horses are challenged with a particular strain of virus. However, most horses don’t live in laboratories: at least not the ones I take care of. Unfortunately, field data – that is, how well the vaccines prevent the flu in barns, stables, and pastures – is extremely limited, and field trials have NOT shown the vaccine to be particularly effective at preventing the spread of influenza. In fact, if you consider that horses are pretty widely vaccinated against the flu (except in Australia, where, with the exception of one outbreak a number of years back, the disease doesn’t occur), and that flu is still a very common problem, you might be drawn to conclude that the vaccine hasn’t been very effective. In general, vaccinated horses will still get infected with flu virus, and even though they may show milder clinical signs of disease, they will still shed virus and so be a source of infection for other susceptible horses.

PLEASE NOTE: If you show your horse, there are many competitions and show organizations that have requirements for flu vaccines – make sure you’re aware of them. This fact is independent of vaccine effectiveness.

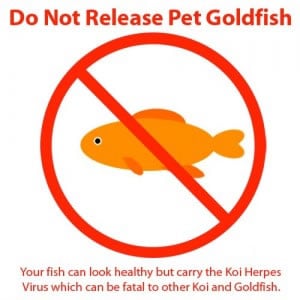

EQUINE HERPES VIRUS (EHV, Rhinopneumonitis, Infectious Abortion, etc.)

There are three scenarios where your horse may be affected by a herpes virus.

1. Pregnancy. EHV (you don’t want me to have to spell it each time, do you?) causes mares to abort their fetuses. And, happily, there is some evidence that EHV 1-4 vaccines (the numbers indicate a vaccine strain) do reduce the likelihood of abortion. However, the vaccines may not work very well if horses exposed to a high dose of the virus, and the rationale behind the 5, 7, and 9 month vaccine schedule ‘s not at all clear. You’ll probably do it if you have pregnant mares, because you’d feel terrible if your mare aborted from the virus, and you didn’t vaccinate.

2. Respiratory Disease. EHV-4 can cause respiratory disease that is pretty much indistinguishable from the flu. There’s some evidence that vaccination can reduced the severity and duration of respiratory disease after an experimental challenge, but it probably doesn’t do anything to stop the spread of the disease, and particularly since many horses are exposed to the virus when they are very young. In fact, latent (inactive) EHV-1 infection is quite common in horse populations worldwide. In fact, it’s been estimated that inactive infections exist in something like 90% of the horses in some areas. Otherwise stated, EHV-1 vaccines probably don’t do much good, because horses are already infected, in the same way that people with cold sores are carriers of the herpesvirus. Vaccination doesn’t help when you’ve already got the disease.

3. Neurological Disease. No EHV-1 vaccine has been shown to prevent the neurologic form of the disease that periodically captures equine health headlines, and no vaccine claims that it can prevent the neurologic form of the disease. Period.

WEST NILE VIRUS

There is good evidence that vaccination against West Nile Virus is effective against preventing clinical disease and death in horses. You should follow the manufacturer’s recommendations, but in some areas, those areas where there are lots of mosquitoes, more frequent boosting may be recommended in order to maximize the protective immunity. Ask your veterinarian for his or her recommendations if you’re in an area where West Nile Virus is a particular problem.

POTOMAC HORSE FEVER (PHF)

PHF is more of a regional disease, mostly seen in the eastern United States. When the disease first came out, a vaccine was rapidly made available, and the early experimental data, which was based on challenge with a selected strain of the disease, was very good. Unfortunately, there’s not much data pertaining to use of the vaccine in the field, and what is there suggests that the vaccine doesn’t work very well. That’s probably because there are many strains of the disease (as I recall, it’s at least nine), but only a couple of strains are in the vaccine. Bottom line is that the PHF vaccine is not likely to provide much protection against disease.

ENCEPHALITIS (Eastern, Western, Venezuelan)

Viral encephalitis is an uncommon, but regularly seen problem that mostly occurs in the eastern United States (VEE doesn’t occur in the US, but it’s occasionally crosses the southern border with Mexico). If your horse gets encephalitis, he simply isn’t going to get better, so vaccination is your best strategy to prevent the disease. Ask your veterinarian for the best vaccination schedule in your area. The vaccine is very effective.

Frankly, there’s very little evidence to suggest that strangles vaccines work. In fact, most of the world doesn’t vaccinate against strangles. In addition, strangles vaccinations have among the higher incidences of vaccine reactions. If you’re using the intranasal vaccine, it’s also possible for your horse to get sick from the vaccine strain of the bacterium. There are some newer vaccines that sound promising, but they’re not here yet.

I don’t recommend that my own clients use the strangles vaccine. And as I said at the start of this article, the vaccine is certainly not a substitute for hygiene, quarantine, and control measures. CLICK HERE for the 2018 position paper on strangles, from the American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine (which does not advocate vaccination).

It works. Vaccinated horses survive tetanus infections, and non-immune horses die. We’re not sure how long the vaccines last, but evidence from other species suggests that it’s measured in years. Your horse is going to get plenty of opportunities to be vaccinated against tetanus if you, like most people, use a combination products (e.g., “Four-Way”) and there’s no evidence that it will hurt him if he gets vaccinated against tetanus every year.

EQUINE VIRAL ARTERITIS (EVA)

EVA is another annoying viral disease, and vaccines are used in distinct regions of the world. These regions generally not include the US; they’re not allowed to be used in the UK. That said, it does seem that the vaccine is effective at preventing the carrier state in vaccinated colts. However, safety concerns about the vaccine exist, the safety of vaccinating pregnant mares is up in the air, and there are some worries about vaccine-caused disease. It’s also pretty much impossible to tell if a horse has been vaccinated, or if it’s been exposed to disease: this can be a concern if you’re planning on shipping a stallion internationally.

RABIES

In some parts of the United States, those with high rabies activity, it’s advisable to vaccinate your horse. Plus, in some states, it’s the law. The available vaccines are effective, and in areas where there is rabies in the wild population, it’s important. Plus, you can get rabies from a horse. Why take that chance?

HOMEOPATHIC NOSODES

You may not have heard of these things, and they aren’t common, but they’re out there. Nosodes (which are not, in fact, homeopathic), are prepared from high dilutions of infectious agents, material such as vomitus, discharges or fecal matter, or infected tissues. Curiously, the founder of homeopathy, Samuel Hahnemann decried the use of such preparations and was even a supporter of smallpox vaccination. There is no evidence at all to suggest that homeopathic nosodes have any effectiveness. To the contrary, there is one case reported in the human literature where a patient followed her homeopath’s advice and took a homeopathic immunization against malaria before traveling to an endemic area. The patient promptly got malaria. Nosodes have also failed to protect puppies against parvovirus. I think that it is of note that the British Faculty of Homoeopathy acknowledges the effectiveness of vaccines and recommends their use in humans. Seriously, just don’t bother with them. Heck, don’t bother with homeopathy, either – CLICK HERE to see why.

A QUICK NOTE ABOUT TITERS – In some circles, people are trying to decide whether or not to vaccinate their horses based on a measure of immunity in the blood. Those measures are called titers. It sounds like a good idea, but there’s actually no information in horses to suggest that a certain titer equals disease prevention. Seems like a good idea, but, in reality, nobody really knows what a particular titer means for a horse.

Oh, one more thing. Don’t fall for all of the negative stuff that some people say about vaccines. They aren’t 100% effective at preventing disease, but they don’t cause widespread harm, either. There are a lot of dopey things said about vaccines – CLICK HERE to read about some of them.

So there. The bottom line is that some vaccines are likely to help your horse(s) – others, not so much – and that nobody really keeps track. That’s why it’s important to work with your veterinarian to establish the ideal schedule for your horse – he or she should have a good idea of particular problems in your neck of the woods.

*****************************************************************************************************************************

* Want more? CLICK HERE to check out the Executive Summary of the Vaccination Guidelines put out by the American Association of Equine Practitioners.