I’m hoping that you’ve already ready Part 1 of this two part article, but, if not, you can CLICK HERE to find it. In Part 1, I started talking about a few of the ways that people can be convinced that a therapy works, even when it doesn’t. Actually, the subject is kind of a big deal, since a lot of therapies (some heavily advertised and promoted) that horse owners are offered really don’t do anything for the horse. Here are some more reasons.

5. Relieving your anxiety vs. curing your horse. If your horse has a problem (or if you think your horse has a problem), you’re probably going to fret. I mean, it’s only natural – if something goes wrong with something you care about, you worry (and not just about the bill). It’s great when you can take care of both the fretting and the condition by curing the problem; then, everyone is happy.

5. Relieving your anxiety vs. curing your horse. If your horse has a problem (or if you think your horse has a problem), you’re probably going to fret. I mean, it’s only natural – if something goes wrong with something you care about, you worry (and not just about the bill). It’s great when you can take care of both the fretting and the condition by curing the problem; then, everyone is happy.

Sometimes, however, the condition – assuming it exists, which is another subject – can’t be cured. Things like old age and arthritis just can’t be fixed. So, given that sobering fact, most people still want to do something to try to “help,” and, to be honest, sometimes it seems that “something” can be pretty much anything.

Seeing a horse in pain, or with a condition that can’t be cured, can cause a very emotional reaction in a person. So, for example, if your horse has arthritis, and is limping, even if you can’t fix your horse, you’ll want to try to make sure that he’s not in pain or discomfort. He’ll feel better – you will, too. Heck, not liking it when horses were sick, and wanting to help take care of their problems was one of the prime motivating factors for me going to veterinary school.

If using a treatment, supplement, or machine helps soothe the emotions and concerns that arise from seeing a beloved animal in pain, treatment benefits may be perceived even if the pain itself remains unaffected. Doing something helps people control their anxieties, redirects their attention, and fosters a sense of control over the problem. In some cases, particularly with a variety of “alternative” therapies, the treatment can even lead to a reinterpretation of the signs of pain (e.g., the dopey chiropractic diagnosis that a horse has a “rib out of place”). If you change someone’s focus, it can help them cope with their horse’s problem, at least temporarily.

If someone perceives that his or her horse suffers less as a result of a treatment, that’s usually a good thing. However, it is important that one’s personal satisfaction with “doing something” not be confused with a cure, and that an ongoing (or worsening) problem not be overlooked while optimistically chasing the next “promising” therapy that might help. Furthermore, you probably don’t need to waste money on some treatment that only makes you feel better, while actually doing nothing for the horse.

SERIOUS ASIDE #1: What I’m saying is that if a person thinks that the horse is better, or thinks that he or she is doing something, they may be satisfied, even if the treatment doesn’t do anything at all. Treatment sellers take that to the bank.

SERIOUS ASIDE #1: What I’m saying is that if a person thinks that the horse is better, or thinks that he or she is doing something, they may be satisfied, even if the treatment doesn’t do anything at all. Treatment sellers take that to the bank.

6. Hedging your bets. Many animals receive more than one treatment at the same time. Often, that means that one treatment or another can receive a disproportionate share of the credit for improvement.

It’s a really curious phenomenon. I sort of liken it to Major League Baseball’s home run hitting record for brothers. In the history of baseball, the brothers who hit more home runs than any other brothers in history were the Aaron brothers, Henry and Tommie. Together, they hit 768 home runs! Of those, Henry hit 755. When it comes to therapies, the way people hedge their bets, it’s like giving all the credit to Tommie!

SERIOUS (well, at least semi-serious) ASIDE #2 – “Ramey’s Rule” states that if several treatments are given at the same time, the strangest one always gets the credit for a good outcome.

7. Misdiagnosis. Many animals owners are afraid that their animals have conditions that they clearly do not have. Take Equine Protozoal Myelitis, (EPM), for example. When if first was recognized, back in the 1990’s, owners and veterinarians were more than willing to ascribe any sort of vague sign of decreased performance or minor, intermittent gait problem (for example, stumbling) to a protozoal infection of the spinal cord. They could even get “diagnosed” with a blood test, or by poking an “acupuncture point” (I am not making this up – for all I know, people are still making an EPM diagnosis based on the response to poking a horse at some spot in the butt with their finger). As a result, many, many horses were treated for EPM. Many also got over whatever their problem was.

Turns out the lots of horses get exposed to the organism that causes EPM. What people didn’t know at the time was that horses test positive on blood tests when they are exposed to the organism, even though they usually don’t get EPM. This wasn’t figured out prior to horses being widely diagnosed and treated. As a result, the vast majority of horses who were treated for EPM didn’t have it. But many of the horses got better, or seemed to get better. Owners and veterinarians were happy. Millions and millions of dollars were wasted treating a problem that mostly didn’t exist. Go figure.

Turns out the lots of horses get exposed to the organism that causes EPM. What people didn’t know at the time was that horses test positive on blood tests when they are exposed to the organism, even though they usually don’t get EPM. This wasn’t figured out prior to horses being widely diagnosed and treated. As a result, the vast majority of horses who were treated for EPM didn’t have it. But many of the horses got better, or seemed to get better. Owners and veterinarians were happy. Millions and millions of dollars were wasted treating a problem that mostly didn’t exist. Go figure.

SERIOUS ASIDE #3 – Your horse can get better from a problem he never had.

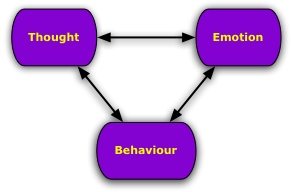

8. Psychological distortion of reality. Distorting reality in the face of a strong belief is a pretty common psychological phenomenon. Even when there are no improvements – even when improvements aren’t possible – people who have a strong psychological investment in a therapy can convince themselves that the therapy has helped. According to a psychological theory known as cognitive dissonance, when experiences contradict existing attitudes, feelings or knowledge, this can cause mental distress.

8. Psychological distortion of reality. Distorting reality in the face of a strong belief is a pretty common psychological phenomenon. Even when there are no improvements – even when improvements aren’t possible – people who have a strong psychological investment in a therapy can convince themselves that the therapy has helped. According to a psychological theory known as cognitive dissonance, when experiences contradict existing attitudes, feelings or knowledge, this can cause mental distress.

People tend to resolve their mental distress by reinterpreting (distorting) the offending information. So, for example, if a person has spent a bunch of money on a new machine, or an unproven therapy, that person has a vested interest in seeing some benefit, even it there’s no benefit to be had. It’s hard for a person to admit that he or she has been fooled, or has wasted money. To get no relief for the horse after committing time, energy and money to a treatment can create mental distress. So, rather than admit to themselves that the treatment has been a waste of time and money, many people will find some redeeming value in the treatment (Otherwise stated: “I think he’s a bit better.”)

This happens to both doctors AND clients who want to believe that their pet therapy “works.” If someone is thoroughly invested in a therapy, the last thing in the world they want to believe is that it doesn’t work. As such, people will often vigorously defended an ineffective treatment by warping perception and memory. Practitioners and clients tend to remember things as they wish they had happened. They may be selective in what they remember, overestimating successes while ignoring, downplaying or explaining away failures. Or, they may just be flimflam artists… there’s a whole history of that in medicine!

This happens to both doctors AND clients who want to believe that their pet therapy “works.” If someone is thoroughly invested in a therapy, the last thing in the world they want to believe is that it doesn’t work. As such, people will often vigorously defended an ineffective treatment by warping perception and memory. Practitioners and clients tend to remember things as they wish they had happened. They may be selective in what they remember, overestimating successes while ignoring, downplaying or explaining away failures. Or, they may just be flimflam artists… there’s a whole history of that in medicine!

9. The Norm of Reciprocity. People might also conclude that a therapy worked due to the demand characteristics that are found in any therapeutic setting. Here’s how this works. People normally feel obligated to reciprocate when somebody does them a good deed; they want to return good intentions with good comments or feelings. For the most part, anyone who is treating your horses is likely to sincerely believe that he or she is helping the horse. Given people’s normal responses to someone doing something nice for them, it is only natural that horse owners would want to please the caregiver in return. Without realizing it, these good feelings are enough to inflate the perception of how much benefit has been received from a treatment.

9. The Norm of Reciprocity. People might also conclude that a therapy worked due to the demand characteristics that are found in any therapeutic setting. Here’s how this works. People normally feel obligated to reciprocate when somebody does them a good deed; they want to return good intentions with good comments or feelings. For the most part, anyone who is treating your horses is likely to sincerely believe that he or she is helping the horse. Given people’s normal responses to someone doing something nice for them, it is only natural that horse owners would want to please the caregiver in return. Without realizing it, these good feelings are enough to inflate the perception of how much benefit has been received from a treatment.

What’s the bottom line? (I thought you’d never ask). Many false leads can convince intelligent, honest people that cures or improvements have been achieved when, in fact, they have not. It’s not just enough to want to do some good – someone who is taking money for a therapy should really be doing good. That’s why therapies are supposed to be tested to see if they actually work, under strict scientific conditions that control for placebo responses, compliance effects and judgmental errors before it can be deemed to be effective.

What’s the bottom line? (I thought you’d never ask). Many false leads can convince intelligent, honest people that cures or improvements have been achieved when, in fact, they have not. It’s not just enough to want to do some good – someone who is taking money for a therapy should really be doing good. That’s why therapies are supposed to be tested to see if they actually work, under strict scientific conditions that control for placebo responses, compliance effects and judgmental errors before it can be deemed to be effective.

Unfortunately, that’s not how it often works in the real world. You’re going to be looking for the “best” for your horse. Pretty much nobody is worried about the lack of scientific support for a product or service that they are selling. But for you, there’s one important thing to remember: If there’s a lack of good evidence for a treatment, it’s a good idea to avoid it, unless you’re happy having your horse serve as an uncontrolled experiment.

To people with an animal that is, or is perceived to be, unwell, any promise of a cure is intriguing. As a result, common sense can easily be replaced by false hopes. In this vulnerable state, the need for careful analysis and awareness is especially necessary. Unfortunately, it seems that instead, an eagerness to accept any treatment that offers some hope often takes over. Both givers and receivers of therapies should always be aware of the intellectual dangers of trusting personal experience and of the reasons why things sometimes seem to work (even when they don’t).

To people with an animal that is, or is perceived to be, unwell, any promise of a cure is intriguing. As a result, common sense can easily be replaced by false hopes. In this vulnerable state, the need for careful analysis and awareness is especially necessary. Unfortunately, it seems that instead, an eagerness to accept any treatment that offers some hope often takes over. Both givers and receivers of therapies should always be aware of the intellectual dangers of trusting personal experience and of the reasons why things sometimes seem to work (even when they don’t).