If you’ve gone over the 2013 AAEP Guidelines (CLICK HERE to see my summary), you’ve probably (hopefully) gotten the idea that instead of just deworming all the time, it’s a good idea to do periodic fecal eggs counts to see how badly – or if – you horse is affected by parasites prior to deworming him. But no matter how closely you adhere to those guidelines, one question still nags. “What about all those other worms, you know, the ones where fecal egg counts may not be as useful?” This article is about those other bad boys: tapeworms, bots, ascarids, and pinworms.

These “other” worms are a bit different than the worms for which fecal egg counts typically recommended. For one, they have different life cycles. For two, they don’t lay very many eggs, and fecal counts aren’t that useful for finding them. But they occasionally have some health implications for horses, and I figure you should know about them. Here goes.

BOTS (Gasterophilus spp.)

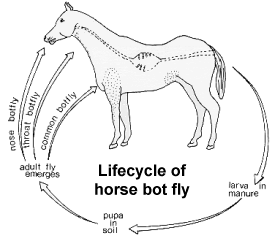

Depending on the part of the country in which you live, you may have noticed these big, annoying, bee-looking flies buzzing around your horse(s) and driving everyone crazy. Bot flies show up in the summer time, and lay their yellow eggs on the horse’s lower limbs (you can’t find them in the horse’s poop). The horse will lick the eggs off, and adult bots develop and attach inside the horse’s stomach.

Depending on the part of the country in which you live, you may have noticed these big, annoying, bee-looking flies buzzing around your horse(s) and driving everyone crazy. Bot flies show up in the summer time, and lay their yellow eggs on the horse’s lower limbs (you can’t find them in the horse’s poop). The horse will lick the eggs off, and adult bots develop and attach inside the horse’s stomach.

Mostly, bots are icky (that’s a medical term) and annoying. But they are rarely associated with any real health problems for horses, although it was reported way back in 1938 by some Hungarian veterinarians…

CLICK HERE if you want to read about them, which I did, mostly because I haven’t met any Hungarian veterinarians.

… that when bot flies get in the horse’s rectum, they can cause itching, straining, colic, increased frequency of defecation, and even prolapse of the rectum (essentially, it turns inside out). Even so, as icky as they are and with the occasional documented health problem, you don’t necessarily have to make yourself crazy trying to get rid of them. That said, I do think it’s a great idea to clip the hair off you’re horse’s lower legs, or scrub, scrub, scrub to remove bot eggs, because by doing that, you can help prevent infections, and well, just keep the overall yuck factor down.

Most commonly, people recommend treating for bots once a year, in the late fall or early winter, or, as is commonly said, 30 days after the first frost. Ivermectin and moxidectin work great, and when you clean them out with the dewormer, you get the benefit of helping to decrease transmission in the following year, too. Plus, you get to of kill a bunch of other worms, too (as long as they aren’t resistant).

TAPEWORMS (Anoplocephala perfoliata – say that fast three times)

It’s kind of hard to say how big a problem tapeworms are in horses. Some areas of the United States have reported as many as 50% of horses have them, but surveys really haven’t been done in very many places, so the true incidence of infection is a bit of a question mark. Tapeworms pass through mites that live in moist pastures – that’s why folks that live in deserts, like southern California, Arizona, or Saudi Arabia can probaby skip to the next section.

It’s kind of hard to say how big a problem tapeworms are in horses. Some areas of the United States have reported as many as 50% of horses have them, but surveys really haven’t been done in very many places, so the true incidence of infection is a bit of a question mark. Tapeworms pass through mites that live in moist pastures – that’s why folks that live in deserts, like southern California, Arizona, or Saudi Arabia can probaby skip to the next section.

Nobody really paid much attention to tapeworms in horses until a bit more than a decade ago, when it was reported that tapeworms can colic in horses, and several studies, in places like Sweden and the Netherlands have concluded that there’s probably an association. But how big a problem it really is is still a matter of discussion in the veterinary parasitology community (these are not discussions that you want to miss Family Guy for, I promise you). Still, most of the times when horses colic as a result of tapeworms, it’s because they have pretty heavy parasite loads; on the other hand, most of the time horses have tapeworm infections, they don’t carry very many worms, and those worms that are there don’t really do much harm.

Trying to figure out if your horse has a tapeworm infection can be a bit of a bother, too. They don’t lay a lot of eggs, and, as a result, infections with tapeworms are hard to diagnoses using common egg count methods. It is possible to check for tapeworms by taking a blood test. How useful those tests are is a bit of a question, however, because horses can be positive on a blood test even after they’ve gotten rid of the parasites. Unless a horse has a whole bunch of tapeworms, finding an egg in the feces is sort of like hitting the fecal lottery, without the return. If you find eggs, it really doesn’t matter how many there are – you should just interpret a test as being positive or negative.

Trying to figure out if your horse has a tapeworm infection can be a bit of a bother, too. They don’t lay a lot of eggs, and, as a result, infections with tapeworms are hard to diagnoses using common egg count methods. It is possible to check for tapeworms by taking a blood test. How useful those tests are is a bit of a question, however, because horses can be positive on a blood test even after they’ve gotten rid of the parasites. Unless a horse has a whole bunch of tapeworms, finding an egg in the feces is sort of like hitting the fecal lottery, without the return. If you find eggs, it really doesn’t matter how many there are – you should just interpret a test as being positive or negative.

If you do get a positive test for tapeworms in your horse, deworming products that contain the drug praziquantel, or a double dose of pyrantel pamoate are the way to go. Since infections are so difficult to diagnose, a single annual treatment after it gets cold (like with bots – and there are combination products that kill both – may not be a bad idea, especially if you’re horse lives in a moist pasture. If your horse lives where it’s dry, and you’re worried, you might want to have a serum test done. If your horse had a low or a negative titer, you could sleep easy, and not worry about treating him for tapeworms.

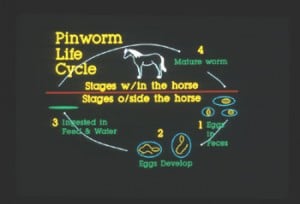

PINWORMS (Oxyuris equi)

Pinworms are a pain in the rear, and, yes, I’m making a pun. Pinworms aren’t all that common, and they don’t really cause serious health problems in horses, but when they cause problems, the horses go nuts. That’s because in the more severe cases, when the adult worm crawls out of the rectum and lays its eggs on the horse’s backside (this is not a pretty image, I admit), the eggs can cause an intense itching. This doesn’t happen to all horses – some horses can have pinworm infections and seem not to be bothered in the least.

ASIDE: People are like that too, come to think about it. The same thing that really bothers one person isn’t a concern at all for another. Go figure.

ASIDE: People are like that too, come to think about it. The same thing that really bothers one person isn’t a concern at all for another. Go figure.

When infected horses rub, they spread their eggs around to walls, feeders, or anything else they can rub on, and parasite transmission occurs by contact with such surfaces, as well as through contact with brushes, tail wraps, and the like. The eggs are pretty tough, too, and they can last in the environment for a long time.

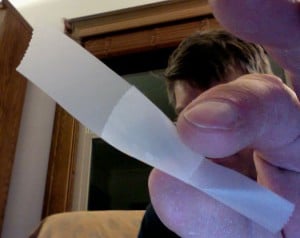

Pinworm eggs don’t commonly show up in fecal exams, either. The more sensitive tests are the “Scotch Tape Test,” where you wrap your fingers in scotch tape, sticky side out, and see if you can get some eggs on the tape (in the same manner that you’d use a lint roller on clothes), or scrapings of the area around the horse’s rectum.

There are reports of resistance by pinworms to most of the deworming agents, but most of the common dewormers are pretty effective. In some cases, veterinarians may even put deworming pastes directly into the rectum, to try to get higher levels of dewormer concentrated in the area of infection. But don’t just rely on deworming – take the time to thoroughly scrub your horse’s backside to remove any eggs that the female worm may deposit (and then wash the things that you used to wash your horse with, too, with soaps or disinfectants).

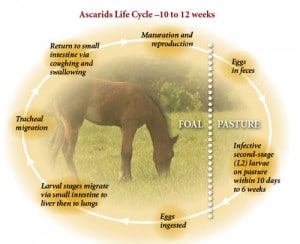

ASCARIDS (Parascaris equorum)

Ascarids cause the most mischief in foals. After ascarid eggs are eaten by the foal, they match and develop into larvae. Unfortunately (for the foal – the parasites are apparently just find with the state of affairs), the larvae can migrate all over the inside of the poor foals’ body, causing foals to look sick, and to grow poorly. Larvae in the foal’s lungs cause inflammation, cough, and nasal discharge; larvae in the intestines can block things up in the small intestines, and cause colic, and even death (usually from intestinal rupture). So it’s a good idea to deworm your foals on a schedule recommended by your veterinarian, based mostly on the foal’s environment and how many other foals he or she runs around with.

Ascarids cause the most mischief in foals. After ascarid eggs are eaten by the foal, they match and develop into larvae. Unfortunately (for the foal – the parasites are apparently just find with the state of affairs), the larvae can migrate all over the inside of the poor foals’ body, causing foals to look sick, and to grow poorly. Larvae in the foal’s lungs cause inflammation, cough, and nasal discharge; larvae in the intestines can block things up in the small intestines, and cause colic, and even death (usually from intestinal rupture). So it’s a good idea to deworm your foals on a schedule recommended by your veterinarian, based mostly on the foal’s environment and how many other foals he or she runs around with.

You probably want to treat foals for ascarids with benzimidazole type drugs (there are lots) because it you deworm with a drug that a paralyzes the worms (like ivermectin), it’s possible to block up the foal’s gut with paralyzed worms. Plus, it’s been documented that ivermectin and moxidectin don’t work very that well on ascarids. The darn things are just about everywhere in breeding operations, and the eggs are pretty tough too (the can remain infectious for a few years).

You probably want to treat foals for ascarids with benzimidazole type drugs (there are lots) because it you deworm with a drug that a paralyzes the worms (like ivermectin), it’s possible to block up the foal’s gut with paralyzed worms. Plus, it’s been documented that ivermectin and moxidectin don’t work very that well on ascarids. The darn things are just about everywhere in breeding operations, and the eggs are pretty tough too (the can remain infectious for a few years).

The importance of ascarids in young horses, and their rapid life cycle, and their low level of egg shedding, is why many folks may choose not to bother with doing fecal exams on foals, particular in situations where there a lot of them (foals). And while ascarids can occasionally be seen in adults, ascarid infections are pretty darn rare, mostly because adult horses become immune to them.

What you should do for your horse depends a lot on where you live. For example, in southern California, I haven’t seen a horse with bots in a couple of decades (I remember one that shipped in once, but that’s different). Tapeworms aren’t really seen here, either, and there aren’t that many foals. But in your horse’s setting, maybe a deworming in the late fall for tapeworms and bots makes a lot of sense, along with occasional fecal egg counts to see how things are going. Every situation is different, and your veterinarian or a local university parasitologist should be an excellent source of more specific information.

What you should do for your horse depends a lot on where you live. For example, in southern California, I haven’t seen a horse with bots in a couple of decades (I remember one that shipped in once, but that’s different). Tapeworms aren’t really seen here, either, and there aren’t that many foals. But in your horse’s setting, maybe a deworming in the late fall for tapeworms and bots makes a lot of sense, along with occasional fecal egg counts to see how things are going. Every situation is different, and your veterinarian or a local university parasitologist should be an excellent source of more specific information.