I cannot imagine that I am the only person who wishes that I could predict the future. Try as I might, I just can’t. Not even if I have an X-ray machine.

I cannot imagine that I am the only person who wishes that I could predict the future. Try as I might, I just can’t. Not even if I have an X-ray machine.

The reason that I bring this up is that for essentially all of my career, people have been asking me to take X-rays of their horse in order to see what might happen to them. And, for essentially all of my career, I’ve been telling them that I can’t do that. I mean, I can take X-rays, I just can’t predict the horse’s future based on what I see.

Others, however, appear to feel differently.

The reason that I say this is that there are times – especially on examinations conducted when a buyer is looking at a horse (prepurchase exams) – when I will be asked to take X-rays (radiographs, if you must) on a horse to, “See if he’s going to hold up,” or to, “See if something might happen to him.” There are other times when a bewildered how owner contacts me about a set of X-rays that a buyer has had taken, a set of X-rays by which it was concluded that his or her horse, who had heretofore never refused a jump, taken a lame step, or otherwise done anything at all to make the owner think that there was anything remotely wrong, was suddenly on the brink of permanent and irreversible unsoundness. At least at some point down the road.

These times make me shake my head. For all of their virtues, X-rays are not high tech crystal balls.

These times make me shake my head. For all of their virtues, X-rays are not high tech crystal balls.

WHAT ARE X-RAYS?

X-rays are a wondrous, albeit quite old, technology. They were first recognized by the inimitable Dr. Marie Curie, the French-Polish physicist who worked around the turn of the 20th century, winning not one, but two Nobel prizes, for, among other things, her work on radiation physics. X-rays pass right through tissue and hit a plate (in past years, the plate had X-ray sensitive film in it, but nowadays, many of the plates contain sensors in them that are connected to computers). Denser tissue, such as bone, stops lots more of the X-rays than does less dense tissue, such as tendon or ligament. That’s why when you look at an X-ray, you see bone as white (not much X-ray got through), and everything else gets progressively darker on the image. Air, which doesn’t stop any X-ray at all, is black.

Anyway, when you expose a horse’s limb to a beam of X-rays, you get an image. From there, things can get messy.

Anyway, when you expose a horse’s limb to a beam of X-rays, you get an image. From there, things can get messy.

Enough X-rays have been taken over enough decades where veterinarians have a pretty good idea of what constitutes normal for most horses. So, for example, if you look at X-rays of a horse’s pastern, you can pretty well predict what the image is going to look like in most horses (especially if you went to veterinary school). Normal horses have X-rays that look, well, normal.

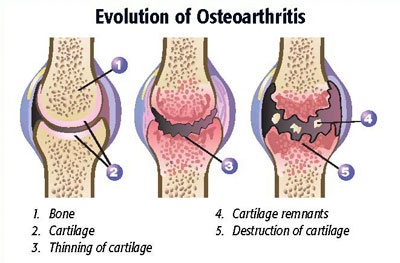

The converse is true, too. That is, if a horse is limping, and he has osteoarthritis of his pastern, X-rays of the pastern may quite clearly show that the joints of the pastern are no longer normal. For example, new bone may be forming around the joint as a result of the osteoarthritis (the “ring” of bone that forms gives osteoarthritis of the pastern it’s time-worn name: ringbone). You can see that on the X-rays – sometimes you can see it from across the barn aisle. You can associate the fact that the horse ls limping with the fact that his joint isn’t normal and go from there (some times, unfortunately, you can’t go very far, but that’s another story).

The converse is true, too. That is, if a horse is limping, and he has osteoarthritis of his pastern, X-rays of the pastern may quite clearly show that the joints of the pastern are no longer normal. For example, new bone may be forming around the joint as a result of the osteoarthritis (the “ring” of bone that forms gives osteoarthritis of the pastern it’s time-worn name: ringbone). You can see that on the X-rays – sometimes you can see it from across the barn aisle. You can associate the fact that the horse ls limping with the fact that his joint isn’t normal and go from there (some times, unfortunately, you can’t go very far, but that’s another story).

These normal and abnormal horses are not what this article is about, however.

This article is about the fact that people usually want X-rays to do more than they can. Especially when they are buying a horse, people what X-rays to tell them whether or not the purchase that they are considering making is a good one. They want to know if, based on interpretation of the X-rays, a horse is going to be unsound at some point in the future.

I completely understand this desire. And I can confidently say two things.

I completely understand this desire. And I can confidently say two things.

- If you buy a horse, even if he looks great at the time of examination, it’s likely that he’s going to have an episode of lameness at some point in the future, especially if you ride him a lot.

- X-rays will not tell you if – or when – it’s going to happen.

You see, there are plenty of very sound horses who have X-rays that would not be considered within the realm of normal, with “normal” being defined as, “What most other horses look like.” Otherwise stated, plenty of very sound horses are blissfully unaware of the precarious state of their X-rays; they go about running, jumping, turning, or prancing just like all of the other horses. The unfortunate fact of the matter is that we – speaking on behalf of everyone who interprets X-rays – have very little idea how or if what we see on X-rays relates to an individual horse’s future. Let’s look at a couple of examples.

This X-ray comes from a sound horse. Or an unsound horse.

NAVICULAR BONES

It was so easy when I first got out of veterinary school. You took X-rays of the horse’s navicular bone, you saw a few “lollipops” (or channels, or invaginations, or whatever), and BINGO, the horse had navicular disease. However, in the decades since, we’ve come to find out that X-rays are rarely diagnostic for the problem in and of themselves. Furthermore, we’ve come to learn that in horses that are otherwise clinically sound, they don’t have predictive value, that is, you can’t (or at least shouldn’t) take X-rays of a horse’s front feet and get some insight into how the horse’s feet are going to hold up in the future; it’s way more complicated than that. In fact, it’s been shown that even though Warmbloods tend to have more “changes” in their navicular bones than do Thoroughbreds, they tend not to be as lame and at least two studies (including one that I did in 1994) have shown that X-rays of a normal horse’s navicular bone won’t tell you if he’s going to go lame at some time down the road.

HOCKS

HOCKS

Horse hocks are very complicated joints. Normal horses can have all sorts of bumps, points, and edges. Plus, with all of the nooks and crannies in the horse’s hock joint, X-rays that are even a little bit off of normal alignment can cause some pretty interesting artifacts. It’s also been shown that horses with hocks that are significantly changed from normal are still able to compete at their expected level. In addition, when horses are lame in their hocks, there doesn’t seem to be any association between the duration and degree of lameness and X-ray findings.

I could go on. For example, horses that have fragments in their first phalanx (pastern) seem to go on trotting just as fast as their unfragmented cohorts, blissfully unaware of the X-ray abnormalities that lurk beneath the surface.

BACKS

BACKS

In human medicine, back X-rays are one big can of worms. That is, some people with terrible back pain have very nice looking X-rays, while some people who have no back pain at all have X-rays that would scare even the most experienced radiologist. It’s the same thing in the horse world. Back X-rays (which seem to be somewhat in vogue now) can look just as “bad” in normal horses as they can in horses with back pain. In clinically normal horses there’s been no correlation made between back X-rays and any future problems. Nevertheless, some earnest sellers of horses get the unpleasant news that their horse isn’t going to be sold – or that they will have to reduce the price – because of some “problem” identified in the horse’s back. It’s a sad state of affairs, really. A prepurchase exam should be different from a psychic reading.

SO WHY TAKE X-RAYS WHEN YOU’RE DOING A PREPURCHASE EXAM?

Yeah, well, that’s a question, isn’t it? In my opinion, there are mostly two reasons.

To have a record of what the horse looked like at the time you buy him. This might be particularly important if you are buying a horse with the intent of reselling him. With a “normal” set of X-rays, you can (hopefully) show potential buyers how things were when you bought the horse. It’s sort of a defensive measure to protect oneself against opinions made in the future by someone else.

To have a record of what the horse looked like at the time you buy him. This might be particularly important if you are buying a horse with the intent of reselling him. With a “normal” set of X-rays, you can (hopefully) show potential buyers how things were when you bought the horse. It’s sort of a defensive measure to protect oneself against opinions made in the future by someone else.- If you have a horse that’s got some sort of an issue at the time of examination. If you’re looking to buy a horse, and the horse isn’t 100% at the time you look at him (yes, many are, at least in my experience), an X-ray may help you evaluate the area of concern. It makes all the sense in the world to take X-rays of unusual lumps and bumps, or to evaluate why a horse has a stiff or swollen joint. The difference here, of course, is that such horses aren’t “normal,” assuming the definition of normal is, “The way most other horses are.” Bumps, stiffness, and swelling aren’t normal, and such things can be well worth looking into, (assuming that you don’t just walk away in the first place). And it sort of begs this question – “If the horse isn’t sound when you buy him, shouldn’t you maybe think about just not buying him at that time?”

Likely to stay sound – no X-rays

But as for telling, “How he’s going to do?” Not so much. Even in yearling Thoroughbred racehorses – where repositories of X-rays are a staple of sale barns, examined by dozens of veterinarians, there’s very little evidence to help guide purchase decisions when X-ray abnormalities are found.

BOTTOM LINE?

The bottom line, when it comes to taking X-rays of a horse during a prepurchase examination, is that X-rays have to be interpreted in light of how the horse looks. You have to ride the horse – you can’t ride the X-rays. If your veterinarian does see “something” on an X-ray of an otherwise normal horse, it’s pretty much impossible to tell what it means for the horse’s future. If you find a horse that your really like, and he’s got a long history of soundness, and he whinnies every time he sees you, I guess it’s OK if you don’t buy him because he’s got a rough spot on an X-ray somewhere. But you might also be passing on your new best friend for no real reason.